In Place of an Introduction

The expression ‘Golden Age’ is often applied to the period of English children’s books from Carroll to Milne, and it is appropriate in more ways than one. Quite apart from the sheer quality of the books, one observes that many of them seem to be set in a distant era when things were better than they are now. And childhood itself seemed a Golden Age to many of these writers, as they set out to recapture its sensations; Kenneth Grahame even called his first book about childhood The Golden Age.1

Thus writes Humphrey Carpenter of that remarkable eighty-year period during which English and American pens spawned such things as Wonderlands, Secret Gardens, Neverlands and Emerald Cities, a period when many writers chose “the children’s novel as their vehicle for the portrayal of society, and for the expression of their personal dreams.”2

English-language works have always comprised a mainstay of children’s literature, which – before coming into its own as a distinct and autonomous genre – included the great works of the Enlightenment and Romantic periods adapted for young readers. The first reworkings of adult novels began to appear towards the end of the eighteenth century: Daniel Defoe’s The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner made its way into children’s bedrooms throughout all of Europe – in Germany, as Joachim Campe’s Robinson the Younger (1779),3 in Poland as Przypadki Robinsona Krusoe z angielskiego ięzyka na francuski przełożone y skrócone od Pana Feutry, teraz oyczystym ięzykiem wydane (The Adventures of Robinson Krusoe translated and abridged from the English version into French by Pan Feutry, Now Published in its Original Language), translated by John Baptist Albertrandi in 1769. Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, originally written for adults, had a similar fate. Eventually, Swift was joined on bookshelves by other books for children and young adults, among them, the works of Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper and Charles Dickens, whose Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol now belong to the permanent repertoire of the children’s canon.

From Carroll To Tolkien: Establishing A Canon

The true turning point and birth of children’s literature – understood not as the anthologizing of texts borrowed and adapted from the world of adults alongside didactic texts on the moral education of children, but as an autonomous field of artistic and literary creation in which the child is inscribed in the text as a full-fledged addressee4 – was the nineteenth century, or its second half, to be more precise. This period marks the beginning of the so-called “Golden Age” of anglophone children’s literature, in step with a worldwide blossoming of publications for the youngest tier of readers. This Golden Age was inaugurated with Lewis Carroll’s works Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871), swiftly followed by Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868), Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), The Prince and the Pauper (1881) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1876), Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Treasure Island (1883), Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894) and Just So Stories (1902), L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), Edith Nesbit’s Five Children and It (1902) and The Railway Children (1906), Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in The Willows (1908), L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables (1908), J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906) and Peter Pan and Wendy (1911), Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886), The Little Princess (1905) and The Secret Garden (1911), Hugh Lofting’s The Story of Doctor Dolittle (1920), A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at the Pooh Corner (1928), P. L. Travers’ Mary Poppins series, whose first part came out in 1935, and finally, J. R. R. Tolkien’s novel The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, published in 1937 (Appendix – Table 1).

The “Golden Age” of English literature for children therefore runs from the 1860s to the 1930s, amounting to about eighty years of intense and excellent literary production for children. One might take issue with the bookends on either side of this “small epoch,” thus rearranging both its beginning5 and end points, but for the purposes of this essay, I take as my endpoint the outbreak of World War II, which marked a transition into a new form of thought, ushering children’s literature into the contemporary era.6

Why English?

Although the historical moment that marks the early phase of children’s classics is quite meaningful, it did not itself determine the stature, popularity, and timelessness of the works that earned their timeless status on the strength of their own immanent literary worth. Monika Adamczyk-Grabowska writes:

English-language children’s literature has garnered such great notoriety in the world that we often attribute its special characteristics to the genre, and not to a national sensibility. When we speak of “English children’s literature” we often think of books that children and adults alike read with pleasure, books full of fantasy, humor, and a taste of the absurd, an unusual interweaving of realism with fairy tale, books free of irritating didacticism, often eschewing all impulses to moralize. These are works for both children and adults, in which children often behave rather maturely, and adults rather childishly. These are books in which everything is possible, although magic is often seeded in the most banal of places […].7

This Polish translator and scholar of children’s literature characterizes children’s classics as works that have survived the test of time, whose merits still delight viewers throughout the world. These are universal books, catered to children as much as to adults. They steer clear of ponderous didacticism and petty moralism and link the “childlike” to the “mature”, joining these two worlds and offering proof that the realm of imagination can be populated by youngsters and grown-ups alike. These are texts that encourage sensitivity, honoring the measure of fantasy cached within the experience of reality and locating all that is folkloric, oneiric and imaginative within the limits of human experience. These texts treat the child reader with respect, though never without a sense of humor. Their humor occasionally spills into the realm of merry nonsense, sometimes linked with lyricism and nostalgia, and sometimes surfacing in rapid wordplay, puns and language games, reminding us that linguistic invention belongs, in the end, to children. After all, only children remain unburdened by the rigors of grammar that constrain the freewheeling force that is human speech.

All this suggests that the works classified as children’s classics are incomparably difficult to translate and require monumental efforts on the part of any translator seeking to bring to readers of her native tongue a masterpiece of the children’s canon and preserve the original mastery of language without distorting its sense in the process. The translation of children’s literature has its own quirks and rules. Significant among these are the imperative to preserve the text’s readiness to be read out loud, and the correlation between the translated text and original illustrations.8 In spite of all this, the demands that the masterpieces of the canon impose upon translators rarely discourage the latter: all of the anglophone works mentioned above boast a considerable repertoire of translations in many foreign languages,9 to which new titles are added each year, if not each moment.

A Macro(Micro)-Cosm Of Translation

Because of its idiosyncrasies and special character, literary translation always strains towards close proximity with the original text in a tireless pursuit of equivalences (in language, culture, and function) and a constant “negotiation” between its own form and its prototype. The translator strives toward completion through close readings of the text, rendering a product founded on cross-idiom identification with the original. In this sense, the poetics and criticism of translation (or, broadly speaking, all scholarship on the subject of translation) necessarily involve scrutinizing the original and translated texts up close and in detail. In the process, criticism often takes the form of comparative, acute readings of select excerpts of a text, whose implications reveal the various strategies adopted by the translator. By its very nature, translation theory always relies on its own form of micropoetics: a research method for analyzing the word, sentence and paragraph. For those adopting this approach, any attempt at a broad or intersectional view requiring perspectives that are distanced from the text (be they chronological, quantitative or qualitative), seems unthinkable, leaving aside its practicability.

In tension with the tradition and basic tenets of translation theory, I would like to contribute some less traditional tools to translation studies that instead of taking a close view of the original and translated texts stand at a certain remove. Over the micropoetics of translation criticism, I propose the macro- perspective model of “distant reading,” whose first proponent, Franco Moretti, maintains that literature is something that can be measured, insofar as it belongs to the material world.10 His claim goes even further: it is possible to portray literature by means of charts, maps, word trees and graphs.11 It follows that translations should also be quantifiable, measurable, and possible to convey in numbers. In this case, I would like to submit to distanced analysis the Polish translations of English children’s literature of the Golden Age, covering sixteen classics of the anglophone canon as translated into Polish from chronological, quantitative and qualitative perspectives, representing eighty years of original creative output (1870–2017).12

Translations Of English Children’s Classics In Numbers

In her monograph Polish Translations of English Children’s Literature: Problems in Translation Criticism, author Monika Adamczyk-Grabowska brings attention to the rarity of the “text that discusses translations according to distinct thematic categories or genres.”13 In fact, discounting some scattered articles in the field of translation criticism that focus on specific works, Adamczyk-Grabowska’s book remains to this day the only14 academic study from Poland concerning translations of English classics for younger audiences. Her book’s representation of authors and texts is selective and non-comprehensive15 due to the author’s own research objective, which was to develop a new model of translation criticism (one built on detailed comparative analysis of literary works on a number of levels), using English children’s literature as material. The perspective adopted by the Polish scholar and translator is therefore clearly associated with the comparativist and close reading approach to translations, while her selection of texts and authors is compatible with her own stated goal. Monika Adamczyk-Grabowska’s work should also be updated and completed, not only due to the significant gaps in its selective bibliography. Since its publication date, the translation history of anglophone children’s classics has undergone substantial change: a number of new translations of titles already known in Poland have appeared, as well as some newly-translated classics making their debut in the Polish publishing market.

Establishing canons, composing authors’ lists, and periodizing literary output are by their very nature arbitrary actions derived from the specific perspective of the group or individual making these choices. I have tried to create the “Golden Age” canon proposed earlier (comprised of sixteen authors ranging from Carroll to Tolkien) using as many English and Polish-language sources as possible in order to correct, or perhaps complete, the subjective research on today’s readers’ familiarity with English titles and authors. This body of work includes the obvious names and titles – Lewis Carroll, A. A. Milne, Rudyard Kipling, L. M. Montgomery and Frances H. Burnett – in the company of somewhat less popular authors (such as Louisa May Alcott, Beatrix Potter, Kenneth Grahame, Edith Nesbit, and P. L. Travers). A number of authors whose stature within English literature ought to earn them a place in this canon (Charles Kingsley, George McDonald, William Thackeray) have been excluded simply due to the chronology of their major works (falling before the bracket of 1865), or because they are less widely read in Poland. The sixteen writers of the Golden Age are paired with their sixteen most popular literary works for children, although the most popular does not always align with the most frequently translated, for there are many cases in which an author’s least known title has undergone more Polish translation attempts than that same author’s world-renowned masterpiece (such is the case with Frances H. Burnett, whose best-known novel The Secret Garden has one less Polish translation than her earlier and somewhat less popular Little Lord Fauntleroy). Since the selection of individual works for each of the sixteen writers was dictated by pragmatic criteria, the canon presented here, by its very nature, provides a reliable representation of the true English-language classics. For a somewhat more comprehensive picture of the situation, the appendix at this essay’s end includes a table enumerating a broader list of writers together with more of their significant titles (Table 1). The canon of sixteen in chronological order is as follows:

1. Lewis Carroll – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

2. Louisa May Alcott – Little women (1868)

3. Mark Twain – Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876)

4. Robert Louis Stevenson – Treasure Island (1883)

5. Rudyard Kipling – The Jungle Book (1898)

6. L.F. Baum – The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900)

7. Edith Nesbit – Five Children and It (1902)

8. Beatrix Potter – The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902)

9. Kenneth Grahame – The Wind in the Willows (1908)

10. L. M. Montgomery – Anne of Green Gables (1908)

11. Frances Hodgson Burnett – The Secret Garden (1911)

12. J. M. Barrie – Peter Pan and Wendy (1911)

13. Hugh Lofting – The Story of Doctor Dolittle (1920)

14. A. A. Milne – Winnie-the-Pooh (1926)

15. P. L. Travers – Mary Poppins (1934)

16. J. R. R. Tolkien – Hobbit or There and Back Again (1937)

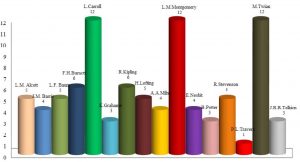

In my project of tracking the history of Polish translations of anglophone children’s classics, I would like to begin with a quantitative perspective, which strikes me as the most fundamental and intuitive method for thinking about translations, and might even seem to provide a portrait of the popularity of these authors and their work. For certain representatives of the canon, however, a quantitative overview of this kind reveals a number of surprises: popularity is not always borne out in numbers. In fact, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, as popular opinion would have it, is in the lead with twelve translations, but shares first place with two other titles: Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. Meanwhile, Winnie-the-Pooh, whose universality and popularity among readers ought to place it right next to Carroll, in fact falls among the least-translated titles, boasting only four Polish translations, while the “translation average” tallies at six.16 As it turns out, the acclaimed Kubuś Puchatek (Polish Winnie-the-Pooh) is translated even less than Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, for instance, which today has dropped in popularity, Lofting’s The Story of Doctor Dolittle and Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, all of which boast five Polish translations (fig. 1).

Figure 1. The allotments of Polish translations for specific authors of the Golden Age

The translations themselves can be organized similarly: they too are subject to canonization. The first Polish translation of Winnie-the-Pooh, by Irena Tuwim in 1938, is treated as the canonical translation, and is praised by most critics and beloved among readers. It is difficult to find any point of contention with the text. Works whose first translation failed to achieve such high stature had a tendency to undergo a greater number of subsequent attempts, especially – as in the case of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland – if they posed compelling and significant tasks to the translator, becoming a measure of the translator’s merit. In my statistical overview of children’s literature in translation, the question of adaptation also becomes important17 – in this article, I do not consider the numerous abridged and adapted versions using the classics as a departure point. Instead, I have sought to enumerate a list of “true translations.” This becomes particularly important since adaptations and reworkings have consistently and integrally accompanied translations of children’s books, and the two formats appear on the publishing market parallel to one another, and often without notes clarifying the distinction between abridged versions and full-fledged translations. If I were to include adaptations in the above data set, the results of the analysis would look very different: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has at least twelve Polish-language adaptations, while The Adventures of Tom Sawyer has only one.

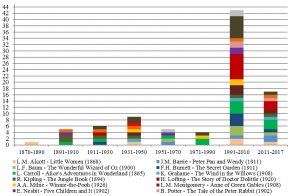

The quantitative perspective remains closely bound to a chronological one, since serial translation sets– both robust and sparse – always unfold in time, and the form they take is often determined precisely by the historical moment in which new texts appear. The graphs below document translation sets of individual English children’s classics of the Golden Years, starting in the 1870s, when the first titles of our canon appeared, and continuing to the present day. (fig. 2).

L. Carroll – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). Fig. 2.1

L.M. Alcott – Little Women (1868). Fig. 2.2

M. Twain – Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876). Fig. 2.3

R.L. Stevenson – Terasure Island (1883). Fig. 2.4

R. Kipling – Jungle Book (1898). Fig. 2.5

L.F. Baum – The Wonderfull Wizard of Oz (1900). Fig. 2.6

E. Nesbit – Five Children and It (1902). Fig. 2.7

B. Potter – The Tale of the Peter Rabbit (1902). Fig. 2.8

K. Grahame – The Wind in the Willows (1908). Fig. 2.9

L.M. Montgomery – Anne of Green Gables (1908). Fig. 2.10

F.H. Burnett – The Secret Garden (1911). Fig. 2.11

J.M. Barrie – Peter Pan and Wendy (1911). Fig. 2.12

H. Lofting – The Story of Doctor Dolittle (1920). Fig. 2.13

A.A. Milne – Winnie the Pooh (1926). Fig. 2.14

P.L. Travers – Mary Poppins (1934). Fig. 2.15

J.R.R. Tolkien – Hobbit (1937). Fig. 2.16

Figure 2. Polish translations of the most famous works of The Golden Age

Reviewing the graphs above might bring about some interesting observations on the form and character of translation sets. It is explicitly clear that authors’ and books’ fates in translation vary vastly when viewed chronologically. Carroll – an author of indisputable status, having existed in Polish letters since 1910 – has seen Polish translations of his work increase consistently since the publication of the first one (by Adela S.), and then substantially accelerate between 2010 and 2015, when a total of six translations appeared, amounting to half of the total set (fig. 2.1). With Twain’s Tom Sawyer novel, the situation unfolds similarly: between the earliest three translations (all dating before 1945) and the fourth translation (published in 1988) lies a pronounced gap of forty years. On the other hand, we observe a pronounced spike beginning in the second half of the 1990s: between 1996 and 2012 eight translations of Adventures of Tom Sawyer were published, amounting to two-thirds of the entire set (fig. 2.3). Two titles intended mainly for an audience of young girls – Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables and Burnett’s The Secret Garden – follow a somewhat different timeline. The translation sets for both titles are characterized by an authoritative first translation: in the case of Anne of Green Gables, Rozalia Bernsztajnowa’s translation from 1911, and in the case of The Secret Garden, Jadwiga Włodarkiewiczowa’s translation from 1908. Both translations attained canonical status and were published in several subsequent editions, which surely accounts for the significant gap between their publication dates and subsequent translation attempts, amounting in both cases to over eighty years, while the bulk of contributions to both translation sets falls between 1995 and 2013 (fig. 2.10 and 2.11). The significantly less extensive translation set of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows also begins at the relatively early moment of 1938, while the subsequent translation in that set does not appear until the beginning of the twenty-first century, over seventy years after Maria Godlewska’s first translation was published (fig. 2.9). Somewhat similar – though less extreme – is the timeline of the five Polish translations of Hugh Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle book: the novel’s first translation, by Wanda Kragen in 1934, is separated from the subsequent attempt by over sixty years, while the penultimate and last translations are separated by a full decade (fig. 2.13) – this last one being the only translation to retain the novel’s long title in Polish in its entirety:18 The Story of Doctor Dolittle, Being the History of His Peculiar Life at Home and Astonishing Adventures in Foreign Parts, translated by Beata Adamczyk in 2010 as Doktor Dolittle i jego zwierzęta: opowieść o życiu doktora w domowym zaciszu oraz niezwykłych przygodach w dalekich krainach. We might refer to Stevenson and Kipling’s Polish translations as the “older” sets, since the greater part of their translations appeared before 1945 (in the case of Treasure Island, three out of five translations, and in the case of The Jungle Book, four out of six existing translations) (fig. 2.4 and 2.5). These sets’ “younger” counterparts, beginning at the end of the 1950s or even into the ‘60s, correspond to J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan and Wendy (the earliest being Maciej Słomczyński’s 1958 translation, titled Przygody Piotrusia Pana: opowiadanie o Piotrusiu i Wendy – fig. 2.12),19 J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, or There and Back Again (the earliest being Maria Skibniewska’s 1960 translation, titled Hobbit czyli tam i z powrotem – fig. 2.16), L.Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (the earliest being Stefania Wortman’s 1962 translation, titled Czarnoksiężnik ze Szmaragdowego Grodu – fig. 2.6) and finally, Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit (the earliest being Mirosława Czarnocka-Wojs’ 1991 translation, titled Opowieść o Króliku Piotrusiu – fig. 2.8). The sparser translation sets (consisting of up to five titles) all developed somewhat consistently, as represented by Louisa May Alcott and Edith Nesbit’s titles, although it is worthwhile to note that Little Women, a novel traditionally for girls, has a great number of older translations (two predating the war, one of which, Zofia Godlewska’s 1875 translation, is the oldest translation from the entire Golden Age canon, with the three remaining translations appearing only after 2000 – fig. 2.2), while most translations of Edith Nesbit’s fantastic tale of the adventures of five children all appeared after 1945 with the exception of one little known and hardly accessible anonymous translation from 1910, titled Dary: powieść fantastyczna (fig. 2.7). Exceptional cases we must reckon with are the earlier contributions to P. L. Travers’ Mary Poppins’ translation set, which is hardly a “set” at all, since it consists exclusively of Irena Tuwim’s 1938 translation, titled Agnieszka (fig. 2.14). This translation was published in several subsequent editions, and in the 1990s its title was modernized, replacing the Polish-rendered Agnieszka with the original first and last names of the series’ protagonist. Travers’ book’s translation history20 – or rather, the book’s noteworthy and puzzling lack of such a history – becomes a curious phenomenon when compared with the translations of the rest of the canon. This is especially surprising since Mary Poppins is extremely popular and widely read in Poland, surely in great part due to the Disney musical adaptation from 1964,21 which could just as well have spurred a natural spike in translations for the funny tales of the Banks family nanny.

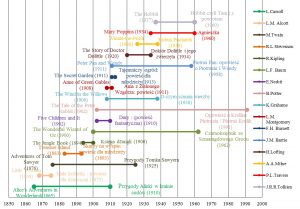

The data sets above merit further scrutiny in one, collated graph (fig. 3) that renders visible the translation careers of the Golden Age children’s classics. After a somewhat leisurely beginning (towards the end of the nineteenth century and at the turn of the century, the first translations from English were still hardly known in the Polish-speaking world)22 we notice a gradual rise in interest in English literature for children that gains steadily. This trend begins with Zofia Grabowska’s above-mentioned translation of Little Women, followed by translations of a few adventure novels: Treasure Island and The Jungle Book. Translations from this period are often published anonymously or attributed only with initials. It seems to be the case that in these years, the translator was treated as one who merely renders a service to the text, and that including her name in the published work was of little importance to the publisher (and perhaps to the translator herself). In the 1910s and ‘20s, the translations of classics become increasingly numerous — in both decades increasing by four titles — including those of Carroll, Nesbit, Montgomery and Burnett, although the true translation boom did not occur until the ‘30s. This is when Irena Tuwim pens her first translations (Kubuś Puchatek / Winnie-the-Pooh; Agnieszka / Mary Poppins). It is also when the first translations appear of Lofting’s novels (Wanda Kragen’s Doktór Dolittle) and of Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (Maria Godlewska’s O czym szumią wierzby).

For obvious reasons, World War II and the immediate postwar period mark a lull in translation: no new authors are translated into Polish, although two new translations of Twain and Stevenson’s titles appear (significantly, both are adventure novels). A resurgence in translation begins only around 1955, when Antonia Marianowicz publishes her translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Three years later, Słomczyński becomes the first to translate Barrie into Polish, and in the early ‘60s, Tolkien and Baum appear in Polish as well. In the immediate wake of this burst of activity comes a period of significant stagnation in translating the canon: between 1963 and 1986, perhaps due to the sociopolitical situation in Poland, the only new translation is Maciej Słomczyński’s Alicja w Krainie Czarów. The late ‘80s mark a renewed period of prosperity for translating the classics that persists today, although of authors not yet translated for Polish readers, we encounter only Beatrix Potter.23

Figure 3. Polish Translations of the Most Famous English-Language Classics of the Golden Age: A Collective Data Set

There remains, however, a definite majority of new translations of English-language writers already familiar to Polish audiences (fig. 4). It is interesting that before 1991, there are only a few cases where two new translations of the same title appear within a twenty-year cycle. Translation sets tend to grow by one title at a time (some exceptions are Twain, Carroll and Kipling, whose translation sets increase by two) and in many cases there are intervals between two new translations of a classic by the same author. Meanwhile, between 1991 and 2010, all authors aside from Stevenson, Barrie, Kipling and Grahame are translated at least twice, with record numbers of translations tallying eight (Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables) and seven (Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer), while Carroll and Burnett are newly translated four times. Such an extreme and stable growth in the volume of translated English children’s classics can be explained, on the one hand, by the rising demand for publications of this kind after a twenty-year lull (1963–1986, fig. 3). On the other hand, perhaps the gradual expiration of the authors’ licensing rights to these titles made them suddenly more attractive to publishers.

Figure 4. The Growth in Translating Classics Viewed in Twenty-Year Cycles (1870-2017)

One more perspective remains, this one exclusively chronological, which requires a subsequent graph that will outline the intervals separating the publication date of the original from its first Polish translations (fig. 5 — titles arranged in chronological order by their original publication date, beginning with Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). It is easy enough to highlight the outliers of this data set: Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of the Peter Rabbit waits the longest for its Polish translation (about ninety years) and Frances H. Burnett’s The Secret Garden has the fastest turnover, its Polish translation appearing on the market only two years after the original. The intervals between the English and Polish publication dates from the first decade of the twentieth century might come as a surprise, as well as those from the end of the nineteenth century. As it turns out, in these periods, publishers and translators had exceptionally quick reaction times to new English-language publications: Alcott’s Little Women had only seven years to wait (1868—1875), Treasure Island ten (1883–1893), Kipling’s Jungle Book six (1894–1900)Edith Nesbit’s book eight years (1902—1910), Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables only three, Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle fourteen (1920—1934) and Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh twelve (1926—1938).

Figure 5. The Intervals between the Original English Publication Date and the First Polish Translation

This is surely due to the sudden boom in the translation of English children’s classics that occurred at the turn of the twentieth century, when books for younger audiences written in the language of Shakespeare and Milton inspired not only a flurry of translations, but a boom in original Polish children’s literature as well.24

The last tool I would like to propose as an aspect of “distant reading” is the qualitative perspective. This is not, however, related to traditional methods of reading and analyzing translations in comparison with their original texts or with other translations in an effort to evaluate their competence. This tool consists of investigating the reception of titles within the fields of translation criticism, literary studies, linguistics, and translators’ polemics and debates, and finally, among the works’ readers. This perspective requires an in-depth and long-ranging sample of secondary texts. Here, I would like to present only an outline of such a study, including only the cursory results of some research into thematic bibliographies and library catalogs.

In terms of volume, Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has garnered the greatest number of critical texts by a large margin, leading in terms of the range of works, the translation issues associated with the work, and the number of translators. The translation set accompanying Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is the subject of its own monograph, devoted solely to its Polish translations (Ewa Rajewska, Dwie wiktoriańskie chwile w Troi, trzy strategie translatorskie. “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” i “Through the Looking-Glass” Lewisa Carrolla w przekładach Macieja Słomczyńskiego, Roberta Stillera i Jolanty Kozak, Poznan, 2004). It comes as no surprise that the list of publications from the disciplines of translation criticism and linguistics, together tallying over sixteen titles, includes texts by authors of recent translations, including Jolanta Kozak and Robert Stiller.25

Second to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the children’s classic in translation that has received the most critical attention is Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. Interest in this text surged only after the publication of Monika Adamczyk-Grabowska’s translation, which challenged Irena Tuwim’s canonical translation. In 1986, when the new translation appeared (titled Fredzia Phi-Phi), numerous articles, debates and polemics began to appear in the press and in literary magazines to discuss the translator’s controversial decision, one that shook up the literary community and roused critics to grab their pens in a defensive and aggressive gesture. Not only did the translator herself write about the new Winne-the-Pooh, but Jerzy Jarniewicz, Jolanta Szpyra and Izabela Szymańska as well.26

The remaining English-language classics of the Golden Age are discussed only sparsely in Polish criticism, and in some cases, not at all. A great deal has been written on the translations of Mongomery’s Anne of Green Gables,27 however. A few texts have been written on Barrie’s Peter Pan and Wendy,28 and still fewer on the Polish editions of The Secret Garden, although they still amount to a body of criticism.29 The remaining eleven works of the Golden Age canon of English children’s literature have gone unnoticed in scholarship, or have perhaps appeared cursorily in texts that cover much broader issues.

It seems that this state of things bears witness to the condition of Polish criticism dealing with children’s literature, whose development has been staggered and selective, reacting only to exceptional or controversial phenomena and neglecting to comment on more typical content and less idiosyncratic translations, which might in fact include commentary on noteworthy individual translation sets, attending to both the competence of emerging translations and to their publication history. In this light, the current scholarship on the translation of children’s literature is still in an early stage of development, demanding diverse and broader contributions that might (and must) utilize diverse methodologies—not only traditional ones, but newer and less polished ones. In this article, I have tried to work through, test and propose a macro-perspective model of “distant reading” as a new research tool. This strategy argues that the “textual world” of literary translation is compatible with the most diverse methods of reading, many of which we could not have fathomed in earlier years.

Appendix

Table 1. Sixteen Classic Authors of Children’s Literature and their Most Popular Works in Polish Translation

|

L.M. Alcott |

Little Women or Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy (1868) |

Małe kobietki : powieść dla dziewcząt (Z. Grabowska) |

1875 |

|

Małe kobietki: powieść dla dorastających panienek (M. Wiesławski) |

1939 |

||

|

Małe kobietki (L. Melchior-Yahil) |

2000 |

||

|

Małe kobietki (D. Sadkowska) |

2005 |

||

|

Małe kobietki (A. Bańkowska) |

2012 |

||

|

J.M. Barrie |

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906) |

Przygody Piotrusia Pana (Z. Rogoszówna) |

1913 |

|

Piotruś Pan w Ogrodach Kensingtońskich (M. Słomczyński) |

1991 |

||

|

Peter Pan and Wendy (1911) |

Piotruś Pan: opowiadanie o Piotrusiu i Wendy (M. Słomczyński) |

1958 |

|

|

Piotruś Pan i Wendy (M. Rusinek) |

2006 |

||

|

Piotruś Pan i Wanda (W. Jerzyński) |

2014 |

||

|

Piotruś Pan (A. Polkowski) |

2015 |

||

|

L.F. Baum |

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) |

Czarnoksiężnik ze Szmaragdowego Grodu (S. Wortman) |

1962 |

|

Czarodziej z Krainy Oz (M. Pawlik-Leniarska) |

1993 |

||

|

Czarnoksiężnik z Krainy Oz (A. Rajca-Salata) |

1999 |

||

|

Czarnoksiężnik z krainy Oz (P. Łopatka) |

2000 |

||

|

Czarownik z Krainy Oz (B. Kaniewska) |

2013 |

||

|

F.H. Burnett |

Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886) |

Mały lord: powieść dla młodzieży (M.J. Zaleska) |

1889 |

|

Mały lord (S. Kowalewska) |

1957 |

||

|

Mały Lord (A. Skarbińska) |

1994 |

||

|

Mały lord (H. Pasierska) |

1998 |

||

|

Mały lord (P. Łopatka) |

2000 |

||

|

Mały lord (K. Zawadzka) |

2002 |

||

|

Mały lord (J. Łoziński) |

2015 |

||

|

Little Princess (1888) |

Co się stało na pensyi? (J. Włodarkiewiczowa) |

1913 |

|

|

Mała księżniczka (J. Birkenmajer) |

1931 |

||

|

Mała księżniczka (W. Komarnicka) |

1959 |

||

|

Mała księżniczka (E. Łozińska-Małkiewicz) |

1994 |

||

|

Mała księżniczka (R. Jaworska) |

1997 |

||

|

The Secret Garden (1911) |

Tajemniczy ogród: powieść dla młodzieży (J. Włodarkiewiczowa) |

1914 |

|

|

Tajemniczy ogród (A. Staniewska) |

1995 |

||

|

Tajemniczy ogród (B. Kaniewska) |

1997 |

||

|

Tajemniczy ogród (Z. Batko) |

1997 |

||

|

Tajemniczy ogród (P. Beręsewicz) |

2009 |

||

|

Tajemniczy ogród (S. Milaneau de Longchamp) |

2011 |

||

|

L. Carroll |

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) |

Przygody Alinki w krainie cudów (Adela S.) |

1910 |

|

Ala w krainie czarów (M. Morawska, A.Lange) |

1927 |

||

|

Alicja w Krainie Czarów (A. Marianowicz) |

1955 |

||

|

Przygody Alicji w Krainie Czarów (M. Słomczyński) |

1972 |

||

|

Alicja w Krainie Czarów (R. Stiller) |

1986 |

||

|

Alicja w Krainie Czarów (J. Kozak) |

1997 |

||

|

Przygody Alicji w Krainie Czarów (M. Machay) |

2010 |

||

|

Alicja w Krainie Czarów (K. Dworak) |

2010 |

||

|

Alicja w Krainie Czarów (B. Kaniewska) |

2010 |

||

|

Alicja w Krainie Czarów (E. Tabakowska) |

2012 |

||

|

Alicja w Krainie Czarów (T. Misiak) |

2013 |

||

|

Perypetie Alicji na Czarytorium (G. Wasowski) |

2015 |

||

|

Through the looking-glass and what Alice found there (1871) |

W zwierciadlanym domu : powieść dla młodzieży (J. Zawisza-Krasucka) |

1936 |

|

|

O tym, co Alicja odkryła po drugiej stronie lustra (M. Słomczyński) |

1972 |

||

|

Po drugiej stronie Lustra (R. Stiller) |

1986 |

||

|

Poprzez lustro czyli co Alicja znalazła po Tamtej Stronie (L. Lachowiecki) |

1995 |

||

|

Alicja po tamtej stronie lustra (J. Kozak) |

1999 |

||

|

Alicja po drugiej stronie zwierciadła (H. Baltyn) |

2005 |

||

|

Alicja po drugiej stronie lustra (M. Machay) |

2010 |

||

|

Po drugiej stronie lustra (B. Kaniewska) |

2010 |

||

|

Po drugiej stronie lustra (T. Misiak) |

2013 |

||

|

K. Grahame |

The Wind in the Willows (1908) |

O czym szumią wierzby (M. Godlewska) |

1938 |

|

Wierzby na wietrze (B. Drozdowski) |

2009 |

||

|

O czym szumią wierzby (M. Płaza) |

2014 |

||

|

R. Kipling |

The Jungle Book (1894) |

Księga dżungli (anonim) |

1900 |

|

Księga puszczy (J. Czekalski) |

1902 |

||

|

Księga dżungli (F. Mirandola [Pik]) |

1922 |

||

|

Księga dżungli (J. Birkenmajer) |

1936 |

||

|

Księga dżungli (A. Polkowski) |

2010 |

||

|

Księga dżungli (A. Matkowska) |

2016 |

||

|

Just So Stories (1902) |

Takie sobie historyjki (M. Feldmanowa [Kreczkowska]) |

1903 |

|

|

Takie sobie bajeczki (S. Wyrzykowski) |

1904 |

||

|

Bajki o zwierzętach (A. Świejkowska) |

2011 |

||

|

H. Lofting |

The Story of Doctor Dolittle, Being the History of His Peculiar Life at Home and Astonishing Adventures in Foreign Parts (1920) |

Doktór Dolittle i jego zwierzęta (W. Kragen) |

1934 |

|

Doktor Dolittle i jego zwierzęta (M.E. Letki) |

1998 |

||

|

Doktor Dolittle i jego zwierzęta (P. Piekarski) |

1998 |

||

|

Doktor Dolittle i jego zwierzęta (H. Kozioł) |

1999 |

||

|

Doktor Dolittle i jego zwierzęta : opowieść o życiu doktora w domowym zaciszu oraz niezwykłych przygodach w dalekich krainach (B. Adamczyk) |

2010 |

||

|

A.A. Milne |

Winnie the Pooh (1926) |

Kubuś Puchatek (I. Tuwim) |

1938 |

|

Fredzia Phi-Phi (M. Adamczyk-Grbowska) |

1986 |

||

|

Kubuś Puchatek (B. Drozdowski) |

1994 |

||

|

O Kubusiu Puchatku (A. Traut) |

1993 |

||

|

The House at Pooh Corner (1928) |

Chatka Puchatka (I. Tuwim) |

1938 |

|

|

Zakątek Fredzi Phi-Phi (M. Adamczyk-Grbowska) |

1990 |

||

|

L.M. Montgomery |

Anne of Green Gables (1908) |

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza: powieść (R. Bernsztajnowa) |

1911 |

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (P. Pierkarski) |

1995 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (J. Ważbińska) |

1995 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (D. Kraśniewska-Durlik) |

1995 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (E. Łozińska-Małkiewicz) |

1996 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (K. Zawadzka) |

1997 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (R. Dawidowicz) |

1997 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (K. Jakubiak) |

1997 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (A. Kuc) |

2003 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (P. Beręsewicz) |

2012 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (A. Sałaciak) |

2013 |

||

|

Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza (J. Jackowicz) |

2013 |

||

|

E. Nesbit |

The Book of Dragons (1899) |

Księga smoków (A. Ziembicki) |

1992 |

|

Księga smoków i inne opowieści (A. Fulińska) |

2003 |

||

|

Księga smoków (P. Beręsewicz) |

2006 |

||

|

Five Children and It (1902) |

Dary: (powieść fantastyczna) (anonim) |

1910 |

|

|

Pięcioro dzieci i „coś” : powieść fantastyczna (I. Tuwim) |

1957 |

||

|

Pięcioro dzieci i Coś (J. Prosińska-Giersz) |

1994 |

||

|

Pięcioro dzieci i „coś” (P. Łopatka) |

2000 |

||

|

Railway Children (1906) |

Przygoda przyjeżdża pociągiem (W. Ziembicka) |

1989 |

|

|

Pociągi jadą do taty (A. Zięba) |

2003 |

||

|

B. Potter |

The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902) |

Opowieść o Króliku Piotrusiu (M. Czarnocka-Wojs) |

1991 |

|

Piotruś Królik (M. Musierowicz) |

1991 |

||

|

Króliczek Piotruś (A. Matusik-Dyjak, B. Szymanek) |

2016 |

||

|

R.L. Stevenson |

Terasure Island (1883) |

Skarby na wyspie: powieść dla młodzieży (W.P.) |

1893 |

|

Wyspa skarbów (J. Birkenmajer) |

1925 |

||

|

Wyspa skarbów (K. Jankowska) |

1947 |

||

|

Wyspa skarbów (M. Filipczuk) |

2002 |

||

|

Wyspa skarbów (A. Polkowski) |

2015 |

||

|

P.L. Travers |

Mary Poppins (1934) |

Agnieszka (I. Tuwim) |

1938 |

|

Mary Poppins comes back (1935) |

Agnieszka wraca (I. Tuwim) |

1960 |

|

|

M. Twain |

Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) |

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (J. Biliński) |

1925 |

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (M. Tarnowski) |

1936 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (anonim) |

1943) |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (K. Piotrowski) |

1988 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (A. Kuligowska) |

1996 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (J. Sokół) |

1997 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (P. Łopatka) |

2002 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (A. Bańkowska) |

2007 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (P. Beręsewicz) |

2008 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (F. Maj) |

2010 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (M. Kędroń, B. Ludwiczak) |

2010 |

||

|

Przygody Tomka Sawyera (J. Polak) |

2012 |

||

|

The Prince and the Pauper (1881) |

Książę i biedak: powieść (anonim) |

1908 |

|

|

Książę i żebrak (M. Tarnowski) |

1936 |

||

|

Królewicz i żebrak (M. Feldmanowa [Kreczkowska]) |

1939 |

||

|

Królewicz i żebrak (T. Dehnel) |

1954 |

||

|

Królewicz i żebrak (I. Jasiński) |

1993 |

||

|

Królewicz i żebrak (A. Bańkowska) |

1998 |

||

|

Królewicz i żebrak (K. Tropiło) |

1998 |

||

|

Książę i żebrak (M. Machay) |

2009 |

||

|

Książę i żebrak (M. Bortnowska) |

2010 |

||

|

Przygody Huck’a (T. Prażmowska) |

1898 |

||

|

Przygody Hucka: powieść dla młodzieży (M. Tarnowski) |

1934 |

||

|

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) |

Przygody Hucka (K. Tarnowska) |

1974 |

|

|

Przygody Hucka Finna (J. Konsztowicz) |

1997 |

||

|

Przygody Hucka (M. Machay) |

2008 |

||

|

Przygody Hucka Finna (A. Kuligowska) |

2012 |

||

|

J.R.R. Tolkien |

The Hobbit, or There and Back Again (1937) |

Hobbit czyli Tam i z powrotem (M. Skibniewska, W. Lewik) |

1960 |

|

Hobbit albo Tam i z powrotem (P. Braiter) |

1997 |

||

|

Hobbit czyli Tam i z powrotem (A. Polkowski) |

2002 |

translated by Eliza Cushman Rose

The classics of English children’s literature are works that have survived the test of time. These are wise and beautiful books that are simultaneously exceptionally challenging to translate. The eighty-year period of the “Golden Age” of English-language children’s literature was inaugurated with Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and continued with works by authors such as Louisa May Alcott, J.M. Barrie, L. Frank Baum, Frances H. Burnett, Kenneth Grahame, Rudyard Kipling, Hugh Lofting, A. A. Milne, L.M. Montgomery, Edith Nesbit, Beatrix Potter, R.L. Stevenson, P. L. Travers and Mark Twain, who together comprise the canon of best-known literary works for children. The first Polish translations of these English-language classics appeared, in turn, around 150 years ago, towards the end of the nineteenth century. The work of translating the canon has continued throughout the entire twentieth century and into the present day, frequently producing substantial translation sets for individual titles. Polish translation theory has thus far lacked a means for treating the English-language canon and the history of its translations from any other perspective but that of close-reading and comparative analysis of the original and translated texts of individual titles. This essay’s objective is to propose the model of the macropoetics of translation, which might facilitate research on Polish translations of English-language masterpieces for younger readers in the form of overviews, profiles, and intersections, leveraging perspectives that are quantitative (the volume of translations), chronological (how they emerged over time) and qualitative (their reception and critical status), all in keeping with Franco Moretti’s proposition of “distant reading.”

1 H. Carpenter, Secret Gardens. A Study of the Golden Age of Children’s Literature, London–Sydney 1987, p. X. Kenneth Grahame’s collected stories – The Golden Age (1895) – which has been written about and printed twice in Poland under different titles: Wspomnienia z krainy szczęścia: wybór opowiadań, translated to Polish by Andrzej Nowicki (Warsaw 1958) and Złoty wiek; Wyśnione dni, translation and afterword by Ewa Horodyska (Wrocław 1991).

2 H. Carpenter, loc. cit.

3 W. Krzemińska, Literatura dla dorosłych a tworząca się literatura dla młodego czytelnika, [in:] idem, Literatura dla dzieci i młodzieży. Zarys dziejów, Warsaw 1963, p. 30.

4 A fully fledged consumer, but not the only one – it is worth noting the specific phenomenon of the double addressee (or perhaps multiple addressees) of “the masterpieces of children’s literature, which can be read in various spaces, at various times, and on multiple levels of interpretation.” Z. Adamczykowa, Literatura “czwarta” – w kręgu zagadnień teoretycznych, [in:] Literatura dla dzieci i młodzieży (po roku 1980), vol. 2, ed. K. Heska-Kwaśniewicz, Katowice 2009, p. 18.

5 Following Humphrey Carpenter, I take as the beginning of the “Golden Age” the first edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) because of its rank among the international masterpieces of children’s classics. However, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland would never have come about without the precedent of English “pure nonsense,” which grew out of traditional nursery rhymes and counting-out games. As origins, or perhaps forerunners of the Golden Age, we might also mention the works of Edward Lear, whose nonsense poems began to appear in the 1840s (A Book of Nonsense, by Derry Down Derry – 1846; Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets – 1871). Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby (1863) also predates Carroll’s masterpiece by two years, and is likewise acclaimed as a classic of children’s literature. In Poland, however, Kingsley’s writing enjoys little popularity: the sole translation of The Water-Babies by Ewa Horodyska did not appear until 1996, titled Wodne dzieci: baśń dla dziecka lądu; however, his tales about Greek heroes, (The Heroes, Greek Fairy Tales – 1856) enjoyed greater success, translated by Wacław Berent in 1926 and titled Heroje czyli Klechdy greckie o bohaterach. Another masterpiece of children’s literature predating Carroll is the fantasy novel by the author of Vanity Fair, William Thackeray’s The Rose and the Ring (1854), translated to Polish by Zofia Rogoszówna in 1913 and by Michał Ronikier in 1990.

6 “Many thousands of books were destroyed in air-raids, while […] the 1944 Education Act, which abolished fees in state secondary education, gave at least a theoretical impetus to reading. By the end of the war, children’s literature, now established as a respectable full member of the publishing world, was ready to enter an era of unprecedented richness and prosperity.” P. Hunt, Retreatism and Advance, [in:] Children’s Literature. An Illustrated History, ed. Peter Hunt, Oxford – New York 1995, p. 224. World War II certainly left its mark on English children’s literature, but the transition between the interwar and postwar periods took place quite smoothly: Hugh Lofting began publishing his series in the 1920s, but a number of his Doctor Dolittle books did not appear until the war had ended (eg. Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake – 1948). P. L. Travers’ Mary Poppins series, first introduced in 1935, was continued until the ‘80s, while Tolkien, who published The Hobbit in 1937, did not publish The Lord of the Rings until 1954, even though he began working on it before World War II.

7 M. Adamczyk-Grabowska, O książkach dla dzieci. “Akcent” 1984, issue 4, p. 17.

8 These two features, constituting a major distinction between the translation of literature for adults and children, are elaborated by Michał Borodo (following the Finnish scholar Riitta Oittinen) in his article Children’s Literature Translation Studies? – zarys badań nad literaturą dziecięcą w przekładzie. “Przekładaniec” 2006, issue 1, p. 16.

9 Among often-translated international children’s classics, leading the way is Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s The Little Prince (translated into 300 languages). In April of 2017 this title was proclaimed “the world’s most frequently translated book (with the exception of religious works)”; the runner-up is Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio (translated into over 260 languages), while third place goes to the founding book of the Golden Age of English-language children’s literature – Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which, after Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress is the most frequently translated English-language work, having been translated into over 170 languages both living and dead, including Basque, Tongan, Yiddish, Old English, Cockney English, Zulu, Gothic, Latin, Esperanto and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece, vol. I, eds. John A. Lindseth, A. Tannenbaum, New Castle 2015, p. 739–740; E. Rajewska, Dwie wiktoriańskie chwile w Troi, trzy strategie translatorskie, Poznań 2004, p. 33; Joel Birenbaum, “For the anniversary of ‘Alice in Wonderland,’ translations into Pashto, Esperanto, emoji and Blissymbols” – http://www.alice150.com/wall-street-journal-article-of-june-12-for-the-anniversary-of-alice-in-wonderland-translati ons-into-pashto-esperanto-emoji-and-blissymbols/ [10 Jul. 2017].

10 F. Moretti, Literature, measured (Pamphlet 12), Stanford Literary Lab, April 2016 –https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet12.pdf [10 Jul. 2017]; F. Moretti, Distant Reading, London – New York 2013.

11 Idem, Wykresy, mapy, drzewa. Abstrakcyjne modele na potrzeby historii literatury, trans. T. Bilczewski and A. Kowalcze-Pawlik, Kraków 2016.

12 The first Polish translation of works belonging to the English children’s canon was published in 1875. However, allotting some time for the translation and publication processes at the end of the nineteenth century, it seems that we can take the early 1870s as the beginning point of Polish translations of the Golden Age titles.

13 M. Adamczyk-Grabowska, Polskie tłumaczenia angielskiej literatury dziecięcej. Problemy krytyki przekładu, Wrocław 1988, p. 5. This text’s partial American addendum is Bogumił Staniów’s library studies book, titled Książka amerykańska dla dzieci i młodzieży w Polsce w latach 1944 – 1989. Produkcja i recepcja published in Wrocław in 2000.

14 In 2010, Anna Danuta Fornalczyk’s study Translating anthroponyms as exemplified by selected works of English children’s literature in their Polish versions was published in the series “Warsaw Studies in English Language and Literature.” In this text, the author undertakes a linguistic analysis of Polish translations of character names in the works of Lewis Carroll, J.M. Barrie, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Rudyard Kipling, Hugh Lofting and A.A. Milne.

15 The textual basis of Adamczyk-Grabowska’s research is “9 utworów angielskiej literatury dziecięcej uznawanych powszechnie za klasykę w tej dziedzinie piśmiennictwa z ich 17 przekładami”. The author chooses six authors and analyzes their most famous works: William Thackeray’s The Rose and the Ring, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, Rudyard Kipling’s Just so stories, Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in The Willows, J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Peter Pan and Wendy as well as A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at the Pooh Corner. M. Adamczyk-Grabowska, op. cit., p.44.

16 Here, by “translation average” I mean the value resulting from a simple division of the total existing Polish translations of the canon (ninety) by the number of translated works.

17 There are several conversations ongoing in Polish translation theory circles on the subject of adaptation (as well as the adaptive character of translating children’s literature). Many have written on adaptability, including Irena Tuwim (Sprawa adaptacji. O przekładach książek dla dzieci i młodzieży. “Nowa Kultura” 1952, issue 26, p. 10) and Stanisław Barańczak (Rice pudding czy kaszka manna. “Teksty” 1975 issue 5, p. 72-86), while Monika Adamczyk-Grabowska has polemicized with the concept of adaptation, although in her already-mentioned book Polskie przekłady angielskiej literatury dziecięcej she locates the study of adaptations within the field of translation studies.

18 The question of titling translated works is an interesting one, since it becomes a distinct indicator of the impact of the first translation, which so often becomes canonical and authoritative. The Polish title of Burnett’s The Secret Garden has never been modified throughout the hundred-so years its translation set has been expanding: not one of its translators took issue with Włodarkiewiczowa’s Tajemniczy ogród – a choice that is not, in fact, a perfect equivalent of the original. Similarly canonical and unalterable is Bernsztajnowa’s translated title of Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables – Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza – which has studiously kept hidden the original name of the house where Anne Shirley lived: green gables more literally translates to ”zielonego dachu” than “zielonego wzgórza”, since “gable is an architectural term for the wall connecting two parts of a pitched roof”. (M. Nowak, Strategie tłumaczeniowe w przekładzie antroponimów i toponimów w powieści “Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza Lucy Maud Montgomery”, unpublished text). The titles given to Milne’s works make an interesting case that I’ve already mentioned – the title of Tuwim’s influential translation, whose status is indisputable, has been countered only once by Monika Adamczyk-Grabowska, who called her translation Fredzia Phi-Phi, in defiance of the timelessness of Tuwim’s translation. The new translation, however, (together with its title) was rejected by the majority of its critics and readers, and subsequent translations by Drozdowski and Traut revert back to Tuwim’s canonical title (fig. 2.14). Grahame’s book has a similar story: Godlewska’s first translation – O czym szumią wierzby (1938) – was countered by Bohdan Drozdowski’s Wiatr wśród wierzb (2009). The new translation, however, never managed to oust the prewar title from its prominence, and Maciej Płaza’s newest translation from 2014 returned to O czym szumią wierzby. In many cases, the titles of the most acclaimed works differ only marginally between translations: such is the case with Carroll, Barrie, Potter and Baum.

19 The translation careers of Barrie’s books unfolded somewhat uniquely: Słomczyński’s full-fledged translation is predated by two Polish translations of works from Peter Pan’s world: Przygody Piotrusia duszka, an anonymous translation published in Warsaw in 1913 by M. Arcta, and Przygody Piotrusia Pana in May Byron’s text for children and Alicja Strasmanowa’s translation, distributed in Warsaw by Księgarnia Literacka in 1938. Both adaptations are liberal and succinct with Barrie’s masterpiece, and for a number of years, these were the only available versions of Peter Pan’s stories. Aside from these, one other work was translated: Zofia Rogoszówna’s Przygody Piotrusia Pana from 1913, which is a translation of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), a text five years older than Peter Pan and Wendy. The two are often mistaken for one another.

20 Most volumes of Travers’ popular series were not translated repeatedly – Irena Tuwim remains the sole translator for four of the novels (Agnieszka – 1938, Agnieszka wraca – 1960, Agnieszka otwiera drzwi – 1962, Agnieszka w parku – 1963), while the fifth and sixth parts of the series were translated only in 2014, by Stanisław Kroszczyński (Mary Poppins w kuchni; Mary Popppins od A do Z). The two remaining books of the series were both translated twice: Mary Poppins na ulicy Czereśniowej and Mary Poppins i Numer Osiemnasty – translated by Krystyna Tarnowska and Andrzej Konarek in 1995, and Mary Poppins na ulicy Czereśniowej and Mary Poppins i sąsiedzi – translated by Stanisław Kroszczyński in 2009 and 2010.

21 The impact of film adaptations – especially in the case of Disney animations – on the popularization, rise in interest, and impetus to translate a number of these children’s classics is an extensive subject worthy of further discussion, but if falls beyond the scope of this essay.

22 “English children’s literature arrived quite late to Poland. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries this was due to the English language’s lack of popularity. French and German were widely known, and it was often through these languages that English classics, for children and adults alike, made their way to Polish readers.” M. Adamczyk-Grabowska, op. cit., p. 41.

23 Beatrix Potter might have been known among Polish readers earlier, but not for her acclaimed book on Peter Rabbit. In 1969 Stefania Wortman, the translator of Baum’s books, among many others, translated the tale The Tailor of Gloucester (1903), which was published with illustrations by Antoni Boratyński, a representative of the so-called Polish illustration school.Yet the famous book belonging in this essay’s canon, The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), was translated for the first time in the late year of 1991, at once by two translators: Mirosława Czarnocka-Wojs (in the collection Bajki dla najmłodszych, ill. Jadwiga Abramowicz) and Małgorzata Musierowicz. Musierowicz’s translation is accompanied by her own idiosyncratic illustrations.

24 In the interwar period “translations comprised about 20% of children’s book production, of which translations from English made up the greatest portion, which refreshingly raised the bar for for Polish writing thanks to its special character of optimism, humor, and unimpeded fantasy.” M. Adamczyk-Grabowska, op. cit., p. 42. And in fact, one glance at the map of Polish children’s literature might prompt an interesting hypothesis: the “golden age” of Polish children’s literature, embodied by Korczak, Makuszyński, Brzechwa, Tuwim, Kownacka and Porazińska, began in the twenty-year interwar period – enough time after the resurgence of enthusiasm for translating the English children’s classics that the children who read those classics could grow up and begin to write their own. It is entirely possible that the finest examples of Polish children’s literature came about precisely thanks to the translations of English classics having provided authors with an adequate foundation, but this thesis demands its own research that falls beyond the scope of this essay.

25 Here I will mention only a few exemplary works: M. Kaczorowska, Alice – Ala – Alicja. Język przekładów wobec

języka powieści. Próba oceny, [in:] Między oryginałem a przekładem VIII. Stereotyp a przekład, ed. U. Kropiwiec,

M. Filipowicz-Rudek, J. Konieczna-Twardzikowa, Kraków 2003, p. 235–265; J. Knap, Od Alinki po Alicję – polskie dzieje wydawnicze Alicji w Krainie Czarów. “Guliwer” 2008, issue 1, p. 30–43; J. Kozak, Alicja pod podszewką języka. “Teksty drugie” 2000, issue 5, p. 167–178; R. Stiller, Powrót do Carrolla. “Literatura na świecie” 1973, issue 5,

p. 330–363.

26 I managed to find thirteen texts devoted to the translations of Milne’s most famous book, including: M. Adamczyk-Garbowska, Albo Fredzia Phi-Phi albo Kubuś Puchatek, z M. Adamczyk-Garbowską rozmawia P. Wasilewski. “Tak i Nie” 1988, issue 9; J. Jarniewicz, Jak Kubuś Puchatek stracił dziecięctwo. “Odgłosy” 1987, issue 10; J. Kokot, O polskich tłumaczeniach Winnie-the-Pooh A.A. Milne’a, [in:] Przekładając nieprzekładalne, ed. O. Kubińskiej, W. Kubińskiego, T.Z. Wolańskiego, Gdańsk 2000, p. 365–378; J. Szpyra, Awantura o Misia, czyli o polskiej krytyce przekładu. “Zdanie” 1987, issue 9, p. 48–51; A. Nowak, Fredzia, której nie było, czyli Penelopa w pułapce. “Dekada Literacka” 1992, issue 39, I. Szymańska, Przekłady polemiczne w literaturze dziecięcej. “Rocznik przekładoznawczy” 2014, issue 9, p. 193–208.

27 Five texts: G. Skotnicka, No, to sobie poprzekładamy. “Nowe Książki”1997, issue 3; M. Zborowska-Motylińska, Canadian Culture into Polish. Names of People and Places in Polish Translations of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. “Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Litteraria Anglica” 2007, issue 7, p. 153–161; J. Zarzycka, Igraszki z tłumaczeniami. “Dekada Literacka” 1994, issue 14, p. 9; I. Szymańska, Przekłady polemiczne w literaturze dziecięcej. “Rocznik przekładoznawczy” 2014, issue 9, p. 193–208; M. Nowak, Strategie tłumaczeniowe w przekładzie antroponimów i toponimów w powieści “Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza Lucy Maud Montgomery”, unpublished text.

28 Three texts: Bernadeta Niesporek-Szamburska, Współczesny przekład literacki dla dzieci – sztuka czy kicz? (Na materiale polskich tłumaczeń “Piotrusia Pana” J. M. Barriego), [in:] Sztuka a świat dziecka, ed. J. Kida, Rzeszów 1996, p. 133–146; A. Pantuchowicz, “Nibylandie”: niby-przekłady “Piotrusia Pana”?. “Rocznik przekładoznawczy” 2009, issue 5, p. 145–152; A. Michalska, Jeszcze raz w Nibylandii. O polskich przekładach “Piotrusia Pana” Jamesa Matthew Barriego. Rekonesans eseistyczny, [in:] Wkład w przekład 3, Kraków 2005, p.81–96.

29 Two texts: W. Grodzieńska, Trzy przekłady książek dla dzieci. “Kuźnica” 1947, 15 Dec., p. 10; B. Kaniewska, Komizm i kontekst. Uwagi o polskim przekładzie „Tajemniczego ogrodu”, [in:] Komizm a przekład, ed. P. Fast, Katowice 1997, p.125–135.