Adam Dziadek

ORCID: 0000-0003-4584-5704

a b s t r a c t

A few years ago, while I was working at the Beinecke Library on materials which were to become a part of Aleksander Wat’s archive, I came across galleys of the book of poems Ciemne świecidło, prepared by the poet. The collection of galleys included many comments by the author regarding the layout of each text, fonts, both minor and (sometimes) significant corrections to individual words, as well as long text excerpts. One poem, Na spacerze, especially attracted my attention. Although in the galleys it was dedicated to Zbigniew Herbert, the dedication was removed from the final, 1968 version of the poem. I was wondering why this had happened, especially since the dedication in question introduced a significant intertextual relation: I believe that Na spacerze related directly to two poems by Herbert, U wrót doliny, first published in the book of poems Hermes, pies i gwiazda (1957) and Sprawozdanie z raju, first published in the book of poems Wiersze (London, 1964). The dedication to Herbert may have resulted from other reasons, such as friendly relations between the Wats and the Herberts – confirmed by the correspondence between the two families – or simply from mutual admiration for their poetic work. However, the relationships between the two texts suggest that the dedication resulted from the profoundly shared thoughts of both poets, who elaborated on biblical myths in a highly atypical, original way. The biblical protagonists of the poem Na spacerze go to Eden, which in fact is a labor camp; signposts in U wrót doliny lead to the unloading ramp in a concentration camp; in the dystopian vision of Sprawozdanie z raju, Eden is presented as a totalitarian state. Those poems by Wat would hence be a “hidden intertext” of Na spacerze, which allows for yet another possible way to read Herbert’s poem. It is worthwhile to take a closer look at this relation, which seems very interesting in the light of the elements of the pre-text.

Indicating these “hidden intertexts” is not the only goal here; I would also like to discuss intertextual relations in the context of genetic criticism, to highlight the importance of avant-texts in the shaping of intertextual relations, to treat avant-texts as a gate to the broad field of interpoetics, which can also include research into manuscripts or avant-texts, significant for later interpretations of selected texts, and which changes the perspectives of reading. Archival collections offer many interesting examples allowing for such a broad extension of intertextual fields of studied texts. In the case of the avant-text of Na spacerze, it is possible to identify more reference fields which expand the sphere of intertextual relations. Wat’s poems are only one example of the issue in question, which could be easily expanded to the works of other authors. The identification of avant-texts belongs to the researcher; an avant-text is never ready, it is listed in archives, stored in a specifically-designated place and waiting for being used and further developed. Creating an avant-text based on various, scattered archival materials is the task of researchers.

Today, an “avant-text” can be understood in several different ways. In this paper, its meaning is related to the concept of Jean Bellemin-Noël as enunciated in Le Texte et l’avant-texte, devoted to the galleys of one poem by Oskar Miłosz1. Bellemin-Noël interprets its meaning in the following way: “a collection of notebooks, manuscripts, >>variants<<, understood as everything that physically precedes the poem treated as a text, and that can co-create a system with it”2. Thus, the work on Wat’s archival materials approaches genetic criticism and is related to the analysis and reconstruction of the writing process; in this case, it is about various materials, in which the process of shaping the texts reveals itself. Hence, if we treat those scattered documents from Wat’s archives as “avant-texts”, then according to the principles of Bellemin-Noël’s concepts, they should be read and interpreted only together with the text to which they refer.

According to Pierre-Marc de Biasi, an “avant-text” can be understood in the context of “manuscript genetics”. Genesis documents (genesis dossier) comprise “a material collection of testaments and manuscripts referring to the writing process of the work which we intend to study”3. As de Biasi shows, the catalogue of “genesis documents” can be broad, including all the materials related to the creation of a given text, from archival materials to materials including “external information in relation to the text’s genesis”4 (such as borrowed books, the author’s correspondence and his/her library, etc.). Genesis dossier brushes aside manuscripts of a vague status, and introduces avant-text created by the researcher according to the principles of the scientific method; it comprises a collection of documents organized chronologically, from “plans, sketches, rough drafts, drafts, documentation, the final draft”5. According to de Biasi, an avant-text is significantly different from “studies into genesis”, as it is “a collection of documents regarding the genesis of the work which can be interpreted, whereas the study of textual genesis is a scientific discourse, in which the geneticist interprets and evaluates the writing processes using specialized tools: poetics, sociology, psychoanalysis, etc.”6 Therefore, an avant-text requires an organized, systematized shape – this is the researcher’s task, since the materials comprising genesis dossier are never organized by authors and they never occur in such a shape as to be readily available for analysis. The same situation applies in the case of Aleksander Wat’s Papers – those materials had been collated by the author’s wife (assisted by Alina Kowalczykowa – there is a lot of evidence of her work in Wat’s American archive) before donating them to the Beinecke Library, sorted into boxes and catalogued years after being donated (first the correspondence, and the remaining materials only after 2010)7. However, the fact that these materials are catalogued does not mean that Wat’s archive in Beinecke offers complete avant-texts, readily available for analysis; the researcher is obviously forced to use materials located in different places of the collection.

Situating the concept of “avant-text” in the context of intertextual studies has already been done, for instance, in the excellent thematic-bibliographic research paper on the intertextuality phenomenon published years ago in the Canadian journal Texte8. The paper included the concept of avant-text interpreted in the same way as in the already quoted book by Jean Bellemin-Noël. In the context of developing genetic criticism, this field of interest finally requires development, which is another goal of the present paper.

I will not dwell too much on the concept of intertextuality; even for its creator, it has become – in her own words – a “gadget” at some point of its dynamic development and incredible career in literary studies: “My concept of dialogism, ambivalence or what I called >>intertextuality<<, which I owe to both Bachtin and Freud, were to become gadgets discovered now at American universities.”9 Indeed, intertextual studies have incredibly expanded over a short period of time. Intertextuality, a term defined by Kristeva in 1966, fell on especially fertile ground – soon new variants and prefix varieties started to function (such as divisions into “transtextuality”, “hypertextuality”, “hypotextuality”, “metatextuality”, etc. proposed by Gérard Genette10), as well as specified forms (such as “autarkic intertextuality” by Lucien Dällenbacha11, or “obligatory intertextuality” and “aleatoric intertextuality” by Michaela Riffaterre12), and eventually, as if in an uncontrollable rush of terminological productivity, a proposal to replace “intertextuality” with “heterotextuality”13 was put forward. Over the more than thirty years of its existence, the term, coined towards the end of French structuralism, has been absorbed by almost every dominant trend in literature studies, structuralism, semiotics, hermeneutics, and phenomenology (Hans Robert Jauss, Brian T. Fitch), psychoanalysis (e.g. Jean Bellemin-Noël, Harold Bloom, Shoshana Felman), historical-literary, socioliterary, as well as cultural studies. While observing the expansion of the term and its various transformations, the following comment can be made: intertextuality has become a term that is both necessary and fashionable, and as such is over-exploited, falling into stereotypical conceptualizations, which consequently has led to the loss of its significance in humanities discourse. This is also evidenced by the fact that in the late 90s, the number of publications adopting intertextuality as their methodological basis significantly decreased. The term itself entered literary criticism discourse and became a genuine gadget serving only ornamental functions.

The term enjoyed a great deal of interest among literature theoreticians in Poland in the 80s and 90s of the 20th century, which gradually faded away14. I understand and use this term in the same way as defined years ago by Julia Kristeva15 – it comprises any conscious, deliberate, as well as unconscious (which I would like to highlight, as sometimes it is wrongly reduced to teleological relations) references to other texts; it is a processual phenomenon, which relies on both conscious and unconscious devices, which is closely associated with subject relations of writing and/or reading.

Studies that take into consideration avant-texts can significantly expand the field of intertextual relations, allowing for discovering “hidden intertexts” or “traces of intertext”, which are very important for the final version of possible interpretations of a given text. Whenever possible, avant-texts should not be overlooked in studies into particular works. A careful examination of avant-texts also brings to mind considerations regarding possible ways of editing and reading literary legacies. Digital technology and online publications make it possible for an edition to incorporate all the documents that comprise the avant-text. Thus, the work of reading does not end with the published text only, about which the author themselves made final decisions. Moreover, as shown by archival materials from Beinecke, texts published earlier are still subject to changes and modifications. Wat did not finish working on texts which had already been published; he transformed to a greater or lesser extent texts which he had published many years before in the Parisian Culture or London News, as well as in an earlier book of poems Wiersze (1957). Likewise, he continued to work on Wiersze śródziemnomorskie, and excerpts from JA z jednej strony i JA z drugiej strony mego mopsożelaznego piecyka. The practice can also be observed in other authors, such as Tadeusz Różewicz. However, this applies only to poems which had already been published, excluding the new poem, Na spacerze, which was supposed to be added to Ciemne świecidło. Avant-texts cannot be reduced to conscious, deliberate intertextual devices. Research into Wat’s archive allow us to make avant-texts the basis for psychoanalytical interpretation. In one of Wat’s notebooks, we can read about a dream he had during the night from February 24th to 25th 1961, which would later become the basis for the third installment of Sny sponad Morza Śródziemnego, which shows that at least some parts of the poem were inspired by dreams and thus were dictated by the unconscious16. And although writing down a dream renders it partially-deformed, the text is prompted by unconsciousness, like in the theater – at least some elements of the text emerge from the unconscious. This record of a dream is one of the most important interpretative contexts of the poem in question, as well as many later poems. Their reading cannot be fully detached from their avant-texts included in Wat’s notebooks.

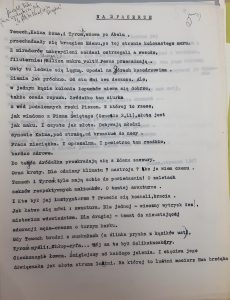

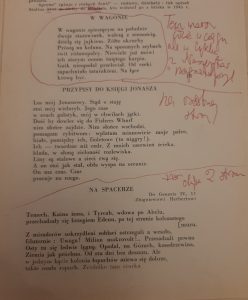

Sorting out the materials comprising the avant-text of the poem Na spacerze is a rather easy task. Below a typescript of the poem can be seen, copied from a manuscript (the poet did the work himself or his wife did it)17:

Box 11 Folder 359: As can be seen, this version does not yet include the dedication. The very practice of copying poems from manuscripts is typical of Wat, who wrote his poems down in various notebooks from which he would later tear individual pages. He would also write poetry on random pieces of paper, or even dust covers, as was the case of the following short poem *** Dla wiersza mego…from the cycle Z naszeptów magnetofonowych (Dla wiersza mego kim jestem? / Tym, kto śni mu się / natrętny. / Gdy otwiera oczy: stoję u wezgłowia, / uzurpator z nożem ofiarnika, / z którego pocieknie wolno / wystygła krew atramentu.)18:

Box 22 Folder 464: In another case, as shown in an excellent paper on textual materiality by Mateusz Antoniuk19, Wat wrote down a poem on a medicine pack. The collections from Aleksander Wat Papers at the Beinecke Library offer many such discoveries, sometimes completely surprising documents, which can be arranged into Wat’s avant-texts. Wat’s manuscripts (as well as many other authors’, such as Czesłąw Miłosz or Zbigniew Herbert) are often characterized by high complexity, which could be generally described as “semiography”, or more specifically, “manuscript semiography”, which goes beyond the scope of this paper (what I mean is, among other things, the fact that when a text that is written down and created, it is accompanied by not only deletions, corrections, modifications, but also drawings and sketches which enter into an inseparable relationship with the text; manuscripts by Czesław Miłosz especially stand out here – a lot of them contain characteristic symmetrical figures, which often take the shape of flowers20).

There is no dedication, but there are a few corrections which will be repeated in the later versions of the text, and finally incorporated into its final version. We have information on the following poem recorded as a numeral, which was supposed to be added to the book of poems Ciemne świecidło (the page numbers of this poem are written in smaller numerals). We can also see a very interesting note by Wat (upper left corner of the page), which introduces another intertextual relation – Phèdre by Racine becomes an important intertext of the poem. Wat writes: »początek trzeba wytłuścić wyrecytować / żeby “La fille de Minos et de Pasipha锫21. This quote indicates Phèdre by Racine (Act 1, Scene 1), and especially an excerpt from Hipolit: “Cet heureux temps n’est plus. Tout a changé de face / Depuis que sur ces bord les dieux ont envoyé / La fille de Minos et de Pasiphaé.” (Glad times are no more / All’s changed since the day /That, to our shores, the gods dispatched / the daughter Of Minos King of Crete: Pasiphae her mother”22). The note on the page was supposed to evoke the sound structure of the French text, one phrase from it, which triggered an intertextual relation, took over someone else’s text and someone else’s thought, which was to be expanded here. Eventually “boldface” did not appear in the final version; however, its incorporation into one of the avant-text’s elements opens other interpretation possibilities, significantly expanding the reference spectrum. Without this piece of information, we would not associate Wat’s text with Phèdre, since there are no indications that we should.

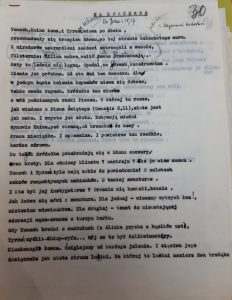

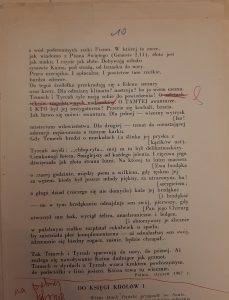

In the following version, devised on the basis of the same typescript, the dedication to Zbigniew Herbert appears. Above the dedication we can also see the following note: “Do Genesis IV, 17”23, which eventually did not appear in the final version either. You can see the page with the dedication below:

The next version of the work in progress can be seen below:

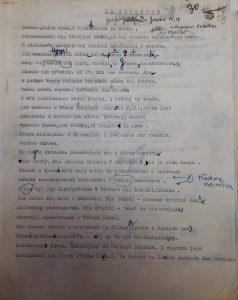

Box 11 Folder 355: The dedication is still there, earlier changes have already been incorporated into the text, there are minor corrections influencing the text’s rhythm, and we can still see the phrase “O zaletach seksów respektywnych małżonków”24, which would be crossed out later in the galleys. The words “tamtej” and “kto” are circled – we learn from the following documents that they are to be boldfaced.

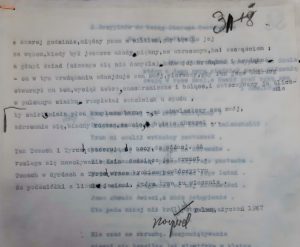

The galleys of the poem look as follows:

Box 11 Folder 369: As can be seen, the reference to Genesis and the dedication are still there. The reference to Genesis does not appear in the final version; most likely it was deemed unnecessary, especially since there is another reference that was preserved in the final version. The above-mentioned sentence disappears from the text, as if it had been too much, a surplus unnecessarily narrowing down or limiting the thematic scope of the wives’ conversation. It is as if the poet assumed that other parts of the text were enough to evoke the erotic context of the conversation as well – it was present in the designed book of poems almost until the end.

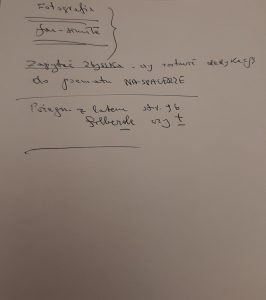

Another element of the text partially explains why the dedication is gone. It is a loose sheet of paper with various notes regarding the edition of the book of poems Ciemne świecidło:

Box 11 Folder 359: This note was not written by the poet; it was made by Andrzej Wat, probably writing down his father’s comments regarding editing the book of poems, as indicated by the handwriting. As can be seen, they refer to a photograph (most likely of the author) which was supposed to be printed in the book of poems, as well as to the poem Pożegnanie jesieni. There is also a note “Zapytać Zbyszka – czy zostawić dedykację do poematu NA SPACZERZE”25. There is no doubt that “Zbyszek” refers to Herbert. It is difficult to explain why the dedication was eventually removed, though probably it was Herbert’s decision. Herbert might have been worried about possible negative consequences of the dedication in a poem about an openly anti-Soviet character. Wat was working on the book of poems in 1967, which eventually would be printed in an emigrant publishing house “Libella” in Paris – this is just one possible explanation for removing the dedication.

The existence of a dedication that was there originally and later deleted remains an observed fact, a research fact that is difficult to ignore while reading Na spacerze, especially when we have access to the materials comprising the avant-text of the poem.

What is the relationship between Na spacerze, U wrót doliny and Sprawozdanie z Raju? The first and the third poem both refer to Genesis, the second one to the Apocalypse. It is difficult not to associate the poems with twentieth-century history, Wat’s experience of a Soviet labor camp, and the fact that Herbert lived in a totalitarian state are two different and at the same time similar historical experiences, or rather extreme existential experiences. There is a special kind of dialogue between these texts; they complete one another, develop biblical motifs, and elaborate on them in many different ways. Herbert uses raw, aloof language, which resembles the language of formal documents, declarations, or announcements, yet he does not refrain from irony, whereas Wat stretches out his poems, uses metaphors, creates elaborate descriptions, circumlocutions, and comparisons, and the blade of his irony is as loud as the rumbling calls of Cain. Both texts use parables – Wat directly refers to the non-literary reality, to a specific historical experience, whereas Herbert employs Aesopian language. Interestingly, Wat left behind an unfinished, moving short story Po śmierci in which he describes a vision of a technocratically organized and managed paradise26. According to Jan Zieliński, the short story may have been written during Wat’s stay in Sopot, where he was supposed to work on a script for a movie about a German philosopher locked up in a hotel, which is at the same time both a concentration camp and the afterworld. According to Zieliński, this may be one of the “parapsychic experiences” (referred to as such by Wat himself) which he had in Sopot in the summer of 1954.

The motif of Cain is developed by Wat in the excellent Poemat bukoliczny (also an unfinished poem – we owe the fact that it exists in the literary world to the efforts of Ola Wat and a lot of editing work by Krzysztof Rutkowski and Jan Zieliński). There are many indications (especially the avant-texts at Beinecke) that the two poems were written almost parallel. At some point, Wat decided to abandon the longer poem and shifted to the much shorter Na spacerze. Frank L. Viogda characterized Poemat bukoliczny as a “midrash”27, i.e. a parable constituting a comment or interpretation of selected excerpts from the Bible (this poem also includes many characteristics of other genres, such as bucolic, farse, etc.). Na spacerze, similarly to other texts by Wat from the cycle Przypisy do ksiąg Starego Testamentu¸ is also a midrash, full of irony, or even sarcasm, emotionally moving due to its intellectual reflection and subtle sensuality. How can one tell the story of a world in which happen such horrible events as senseless acts of violence and revolutions which even God cannot control (there is a suggestion in the poem that God is responsible for it – this motif is confirmed and further developed in Poemat bukoliczny)? An eclectic, ironic text which defies conservative, poetics textbook classifications becomes the only possible form of expression. The world, history, and laughter (bitter laughter!) – these are the only things left in the vision of history presented in the text.

Research into avant-texts allows for uncovering interesting intertextual relations which complete previous interpretations of individual texts in a significant way. They also help realize that any text once published remains open, unrestrained and limitless – thanks to studying avant-texts, the perspective of a given text becomes significantly expanded and allows for many substantial questions closely linked to textual genesis, whose status is never clearly defined. Intertextual space is not limited only to conscious, teleological references, since it opens itself to the unknown and difficult to grasp field of the unconscious.

translated by Małgorzata Olsza

This text is devoted to avant-texts and their influence on intertextual relations. The avant-text research makes it possible to reveal intertextual relations that significantly complement the previous interpretations of indicidual works. They also help realize the fact that any text once printed remains open, uninhibited and unbound – thanks to the research into its avant-texts, reading perspectives are significantly expanded and allow to pose a lot of significant questions related to the genesis of the text. Intertextual space is not limited only to conscious, teleological references, because it opens to the field of the unconscious.

* The present paper is a part of work in progress – a book on genetic criticism entitled Semiografia rękopisu.

1 Jean Bellemin-Noël, Le texte et l’avant-texte: Les brouillons d’un poème de Milosz. (Paris: Libr. Larousse, 1972).

2 Bellemin-Noël, 15. [translation mine, PZ].

3 Pierre-Marc de Biasi, Genetyka tekstów, trans. Maria Prussak and Filip Kwiatek (Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2015), 52.[translation mine, PZ].

4 Biasi, Genetyka tekstów.

5 Biasi, 53.

6 Biasi, 54.

7 Ryszard Zajączkowski wrote about it in Ryszard Zajączkowski, “W archiwum Aleksandra Wata,” Pamiętnik Literacki, no. 1 (2007): 145–61; see also: Adam Dziadek, “Aleksander Wat w Beinecke Library w Yale,” Teksty Drugie, no. 6 (2009): 251–58.

8 Texte Revue de Critique et de Théorie Littéraire., no. 2 (1983). This thematic issue of the Canadian journal Texte entitled L’intertextualité, intertexte, autotexte, intratexte offers an incredibly rich, detailed bibliography of works belonging to several different research fields – all devoted to the question of intertextuality.

9 Julia Kristeva, “Mémoire,” L’Infini (Périodique), no. 1 (1983): 44. The history of the concepts has been analyzed, among others, by Renate Lachmann – see Renate Lachmann, “Płaszczyzny pojęcia intertekstualności,” trans. Małgorzata Łukasiewicz, Pamiętnik Literacki 82, no. 4 (1991): 209–15. I wrote about it more extensively in Adam Dziadek, “Stereotypy intertekstualności,” in Stereotypy w literaturze:

(i tuż obok), ed. Włodzimierz Bolecki and Grzegorz Gazda (Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2003), 67–82.

10 Gérard Genette, Palimpsestes: la littérature au second degré. (Paris: Éd. du Seuil, 1982). Excerpts in Polish: Gérard Genette, “Palimpsesty. Literatura drugiego stopnia,” in Współczesna teoria badań literackich za granicą: antologia. T. 4 cz. 2, ed. Henryk Markiewicz, trans. Aleksander Milecki (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1992), 317-366.

11 Lucien Dällenbach, “Intertexte et autotexte,” Poétique, no. 27 (1976): 282–96.

12 Michael Riffaterre, “La trace de l’intertexte,” La Pensée, no. 215 (1980): 4–18.

13 See Per Aage Brandt, “La Pensée du texte (de la littéralité de la littéralité),” in Essais de la théorie du texte, ed. D’Arco Silvio Avalle et al. (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1973), 184–215.

14 I list only several selected publications here, most important from the Polish perspective: Michał Głowiński, “O Intertekstualności,” Pamiętnik Literacki, no. 4 (1986); (Henryk Markiewicz and Janusz Sławiński, eds., Nowe problemy metodologiczne literaturoznawstwa [Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1992], 185–212). A selection of translated texts on intertextuality: “Pamiętnik Literacki” 1988, vol. 1 and “Pamiętnik Literacki” 1991, vol. 4 (especially papers by M. Pfister and R. Lachmann); Henryk Markiewicz, “Odmiany intertekstualności,” in Literaturoznawstwo i jego sąsiedztwa (Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawn. Nauk., 1989), 198–228; Krzysztof Kłosiński, Mimesis w chłopskich powieściach Orzeszkowej (Katowice: Wyd. Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 1990); Jerzy Ziomek, Janusz Sławiński, and Włodzimierz Bolecki, eds., Między tekstami: intertekstualność jako problem poetyki historycznej (Warszawa: Wydawn. Nauk. PWN, 1992); Ryszard Nycz, “Intertekstualność i jej zakresy: teksty, gatunki, światy,” Pamiętnik Literacki : czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej, no. Tom 81, Numer 2 (1990); (Ryszard Nycz, Tekstowy świat: poststrukturalizm a wiedza o literaturze [Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IBL, 1995], 59–82); Stanisław Balbus, Między stylami (Kraków: Universitas, 1993); Teresa Cieślikowska, W kręgu genologii, intertekstualności, teorii sugestii (Warszawa: Wydawn. Naukowe PWN, 1995).

15 Julia Kristeva, “Le mot, le dialogue et le roman,” in Sēmeiotikē: recherches pour une sémanalyse (Paris: Seuil, 1969), 143–73.The latest translation of this text into Polish: Julia Kristeva, “Słowo, dialog i powieść,” in Séméiotikè: studia z zakresu semanalizy, trans. Tomasz Stróżyński (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, 2017), 59–83. Previously the text was translated by Wincenty Grajewski and published in: Edward Kasperski and Eugeniusz Czaplejewicz, eds., Bachtin: Dialog, Jezyk, Literatura (Warszawa: Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1983).

16 See Aleksander Wat, Notatniki, ed. Adam Dziadek and Jan Zieliński (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IBL, 2015), 680–81; see also Adam Dziadek, “Przed-teksty w „Notatnikach” Aleksandra Wata,” in Archiwa i bruliony pisarzy odkrywanie, ed. Maria Prussak (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IBL, 2017), 123–55.

17 All the materials presented in this text come from the collection houses at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, Aleksander Wat Papers, GEN MSS 705, Series II Writings. Reference to the exact location in the collection is given next to each document. The documents are published with the permission of Andrzej Wat’s copyright holders and his son, Pierre Wat.

18 Who am I for my poem? / The one of whom it dreams / bothersome / When I open my eyes I am standing at the headboard / an usurper with devotion’s knife / out of whom will slowly leak / cool blood of ink [translation mine, PZ]

19 Mateusz Antoniuk, “Jak czytać stronę brulionu: krytyka genetyczna i materialność tekstu,” Wielogłos, no. 1 (2017): 39–66. For me, it is a model text illustrating genetic criticism in practice, in which the avant-text of one of the poems by Aleksander Wat was carefully recreated, with attention to maintaining the chronological order of creating and copying different versions of the text.

20 See Mateusz Antoniuk, Słowo raz obudzone. Poezja Czesława Miłosza: próby czytania (Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka, 2015).

21 »The beginning should be in bold, recited / so that “La fille de Minos et de Pasipha锫 [translation mine, PZ]

22 Jean Racine, Phèdre, trans. Richard Parish (London: Bristol Classical Press, 1996).

23 At Genesis IV, 17 [translation mine, PZ]

24 On the advantages of sex of respective spouses [translation mine, PZ].

25 Ask Zbyszek – should we keep the dedication to Na spacerze? [translation mine, PZ].

26 The short story was first published by me in “Teksty Drugie” 2009 No 6, p. 235-250. A transcript of the story based on an archival notebook was published in Wat, Notatniki.

27 Frank L. Vigoda, “Midrash Cain: A „Pastoral Poem”,” Modern Poetry in Translation, no. 18 (2001): 199–219.

Bibliography:

Antoniuk, Mateusz. “Jak czytać stronę brulionu: krytyka genetyczna i materialność tekstu.” Wielogłos, no. 1 (2017): 39–66.

———. Słowo raz obudzone. Poezja Czesława Miłosza: próby czytania. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka, 2015.

Balbus, Stanisław. Między stylami. Kraków: Universitas, 1993.

Bellemin-Noël, Jean. Le texte et l’avant-texte: Les brouillons d’un poème de Milosz. Paris: Libr. Larousse, 1972.

Biasi, Pierre-Marc de. Genetyka tekstów. Translated by Maria Prussak and Filip Kwiatek. Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2015.

Brandt, Per Aage. “La Pensée du texte (de la littéralité de la littéralité).” In Essais de la théorie du texte, edited by D’Arco Silvio Avalle, Jens F Ihwe, Teun A. van Dijk, Peter Madsen, Charles Bouazis, and Per Aage Brandt. Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1973.

Cieślikowska, Teresa. W kręgu genologii, intertekstualności, teorii sugestii. Warszawa: Wydawn. Naukowe PWN, 1995.

Dällenbach, Lucien. “Intertexte et autotexte.” Poétique, no. 27 (1976): 282–96.

Dziadek, Adam. “Aleksander Wat w Beinecke Library w Yale.” Teksty Drugie, no. 6 (2009): 251–58.

———. “Przed-teksty w „Notatnikach” Aleksandra Wata.” In Archiwa i bruliony pisarzy odkrywanie, edited by Maria Prussak, 123–55. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IBL, 2017.

———. “Stereotypy intertekstualności.” In Stereotypy w literaturze: (i tuż obok), edited by Włodzimierz Bolecki and Grzegorz Gazda. Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2003.

Genette, Gérard. Palimpsestes: la littérature au second degré. Paris: Éd. du Seuil, 1982.

———. “Palimpsesty. Literatura drugiego stopnia.” In Współczesna teoria badań literackich za granicą: antologia. T. 4 cz. 2, edited by Henryk Markiewicz, translated by Aleksander Milecki. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1992.

Kasperski, Edward, and Eugeniusz Czaplejewicz, eds. Bachtin: Dialog, Jezyk, Literatura. Warszawa: Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1983.

Kłosiński, Krzysztof. Mimesis w chłopskich powieściach Orzeszkowej. Katowice: Wyd. Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 1990.

Kristeva, Julia. “Le mot, le dialogue et le roman.” In Sēmeiotikē: recherches pour une sémanalyse, 143–73. Paris: Seuil, 1969.

———. “Mémoire.” L’Infini (Périodique), no. 1 (1983): 39–54.

———. “Słowo, dialog i powieść.” In Séméiotikè: studia z zakresu semanalizy, translated by Tomasz Stróżyński, 59–83. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, 2017.

Lachmann, Renate. “Płaszczyzny pojęcia intertekstualności.” Translated by Małgorzata Łukasiewicz. Pamiętnik Literacki 82, no. 4 (1991): 209–15.

Markiewicz, Henryk. “Odmiany intertekstualności.” In Literaturoznawstwo i jego saąsiedztwa, 198–228. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawn. Nauk., 1989.

Markiewicz, Henryk, and Janusz Sławiński, eds. Nowe problemy metodologiczne literaturoznawstwa. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1992.

Michał Głowiński. “O Intertekstualności.” Pamiętnik Literacki, no. 4 (1986).

Nycz, Ryszard. Tekstowy świat: poststrukturalizm a wiedza o literaturze. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IBL, 1995.

Racine, Jean. Phèdre. Translated by Richard Parish. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1996.

Riffaterre, Michael. “La trace de l’intertexte.” La Pensée, no. 215 (1980): 4–18.

Ryszard Nycz. “Intertekstualność i jej zakresy: teksty, gatunki, światy.” Pamiętnik Literacki : czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej, no. Tom 81, Numer 2 (1990).

Vigoda, Frank L. “Midrash Cain: A „Pastoral Poem”.” Modern Poetry in Translation, no. 18 (2001): 199–219.

Wat, Aleksander. Notatniki. Edited by Adam Dziadek and Jan Zieliński. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IBL, 2015.

Zajączkowski, Ryszard. “W archiwum Aleksandra Wata.” Pamiętnik Literacki, no. 1 (2007): 145–61.

Ziomek, Jerzy, Janusz Sławiński, and Włodzimierz Bolecki, eds. Między tekstami: intertekstualność jako problem poetyki historycznej. Warszawa: Wydawn. Nauk. PWN, 1992.

Texte Revue de Critique et de Théorie Littéraire., no. 2 (1983).