Marta Kaźmierczak

a b s t r a c t

Assumptions and aims

The present contribution is an attempt to explore the interrelation between the notions of quality and seriality in literary translation. Its aim is not, however, judging the “excellence” of the target texts in a normative way, but rather observing certain “quality patterns” in translation poetics.

The concept of translation series has been well established and influential in Polish translation studies, with the methodological point of departure in Edward Balcerzan’s observation made in 1968 that for literary translations it is a series that is the essential mode of existence1. The appearance of even one translation initiates a series which then becomes a potential one. If several translations exist, a series becomes partially realised; partially – because its nature is infinite. The scholar thus insists on a developmental character of the series2.

In the Western translation studies the coexistence of renditions of one and the same work is usually discussed under the name “retranslation.” While the Polish notion of seriality primarily celebrates the plurality of secondary texts, the Western tradition has been dominated by Antoine Berman’s retranslation hypothesis, which assumes the inevitable failure of translation as the premise of successive approximations to the original3. Nevertheless, it also presupposes a striving for improvement in the successive versions4. This “corrective purpose,” although not the only function of translation is also part of Balcerzan’s understanding of translation. George Steiner, too, perceives a succession of alternative versions as “an act of reciprocal, cumulative criticism and correction”5.

Not only the notion of the developmental nature of the series but also certain expressions naturally suggested by the discourse somewhat favour the assumption of a quality increase. Scholars tend to talk of a development (which carries a suggestion of improvement) rather than of accretion, let alone of a degeneration of a series. The marketing uses of “new translation” labels likewise show that the latest addition to a series is believed to hold an attraction6.

However, for a translation series to display a steady growth of quality the following (not always likely) conditions would have to be fulfilled:

1. Translators would have to be aware of the previous elements in the series.

This is not always true, as show investigations by Anna Legeżyńska, who theorised the internal structure of the series7, i.e. the status of particular translations in a series and relations between them. On the one hand, some earlier translations would be marginalised (for various reasons) and would not become points of reference for future ones. On the other hand, additions to the series may be systemic ones (and indeed enter into a dialogue with the previous elements), but some are occasional and show the translators’ lack of knowledge of the work of their predecessors or interest in it. Marta Skwara, in turn, emphasises that a rendition may simply fall into oblivion before a new one appears8.

2. The intent of a translation would have to be to outdo the previous renditions.

Admittedly, dissatisfaction with inadequacy of the existing rendition(s) counts among important retranslation motivations. Even when a translator claims that his aim is showing a different facet of a given work, supplementing rather than negating someone else’s work, still the competitive factor always looms somewhere in the background, as pointedly formulated by the acclaimed translator and critic Stanisław Barańczak,9 who is also one of the “voices” considered in the empirical part of this paper.

However, new translations often emerge for a range of reasons connected not with quality concerns but rather with economic, copyright or ideological factors. To cite a few possibilities:

– A publisher may commission a new translation at a cost lower than that of royalties for the old one – which is not conducive to high quality of the new additions to a series (such consequences of the Polish copyright law were explored by Anna Moc10).

– Józef Zarek cites an instance of a 1980s “underground” Polish collection of Jaroslav Seifert’s poems where translations were signed by pseudonyms; previously published renditions could not be reprinted as they would have given away their authors’ identities11.

– Commissioning a translation may be a matter of ideological patronage and of political exigencies, as pointedly illustrated by the Finnish classic in early-20th-century German versions studied by Pekka Kujamäki12. In such cases new renditions emerge to accommodate socio-historical circumstances, and not out of striving for artistic optimality.

– In recent decades British theatres have encouraged a proliferation of rewrites of world classic drama by “star dramatists”, through whom they intend to attract audiences, a trend described by Helen Rappaport, one of the marginalised language professionals, who “assist from the original”13.

3. Translators would have to be familiar with the state-of-the-art literary studies on a given author or work and also with translation criticism on their predecessors’ versions.

Again, as practice shows, in-depth preparatory studies are not always conducted (or possible), and, especially with poetry, the task may be undertaken for a sheer aesthetic fascination with the original. Jarek Zawadzki’s anthology of Polish school-canon poetry rendered into English14 could exemplify it and this is said by no means with the intention of discrediting his work.

4. Translators would have to be allowed to borrow the most fortunate solutions from their predecessors.

Indeed, Legeżyńska concludes that in this field progress is a collective achievement, and “the rule of plagiarism does not apply”15, at least not on the lower stylistic levels. Practice, however, seems to prove the contrary: translators avoid repeating devices and phrasings after others, and if they do copy, they usually incur criticism16. Furthermore, Grzegorz Ojcewicz has convincingly demonstrated the barrier of plagiarism as a limitation to the development of series. In a short poem, he claims, the successive translations gradually exhaust all possible local solutions and bring the series to its boundaries17.

All in all, as Balcerzan himself famously18 observed, one should not be deceived to believe that he translates best who translates last19. There can be, as noted by Dorota Urbanek, internal and external factors20 conducive to extending the number of retranslations. As a result, the quality of a real-life series, if plotted in a chart, will not often resemble a steadily ascending curve.

What will such a chart look like? I intend to explore it by surveying the Polish renditions of T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Choosing for analysis a modern work of classic status, and one which has attracted translators of stature, I hope to observe an actual quest for quality – if there is one – rather than the need for updating as a retranslation factor. Secondly, although there has been in Poland a period of ideological rejection of Eliot’s poetry (the 1940s were his Purgatory, as one of his translators puts it21), the translations post-date it and apparently none of them was produced to serve political exigencies. The analysis can therefore be expected to yield results connected with poetics of the work(s).

Approach adopted in this study

The phenomenon of translation series has been the subject of theoretical reflection as well as of empirical studies22. To cite Skwara’s enumeration, it can be harnessed, as both material and method, to establishing hierarchies among existing renditions, and besides it to analysing various poetics, languages, dictions characteristic of particular epochs or particular writers, to exploring the diverse interpretations of one text embodied in its renditions, or probing linguistic and cultural differences23. However, Skwara first of all aptly names the limitations of the concept as a methodological tool: she points to the series’ constructed, somewhat artificial character and to the danger of isolating the translations from their socio-historical functioning in the target context24.

Translated poetry is a field in which, on the one hand, seriality becomes most pronounced, and on the other, where quality assessment is most problematic and most often judged subjective. Taking the poetics of a text as a starting point seems to provide a means for objectivising this measurement, a belief reflected in the various concepts of dominants of translation, to name the semantic dominant proposed by Stanisław Barańczak25 and translational dominant theorised by Anna Bednarczyk in response to the former26. These concepts have been proved highly operative, especially if we guarantee the intersubjectivity of such a benchmark tool (as I have argued on an earlier occasion)27.

Yet the poetics of a work often cannot be reduced to one key element. This causes the volatility of approaches in translation criticism. Dorota Urbanek observed that there was no established methodology to analyse series and proposed a rudimentary procedure28. Lance Hewson in his book-length study29 stresses the need for making this field less impressionistic on the one hand, and for measuring interpretative effects (comparing the interpretative potential of the source and target texts) on the other. With his novelistic examples he proposes to do so in a formalised way, by counting specific transformations (or rather their effects) in chosen segments and relating the results to the whole to get the proportion, so as to assess the scale and interpretive effects of changes. An attempt at a similar objectivisation with respect to poetry translation criticism appears worth undertaking.

In the present case, four fields will be studied, important for the overall poetics of the original work: musical qualities of Eliot’s verse, the motif of indecision treated as the thematic core of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, the poetic diction and the intertextual dimension of the piece. The discussion will be organised around subsets of smaller components or aspects observed in the source text, whose retention or loss can be checked in a more specific manner. The appraisal will be aimed not so much at gauging the effectiveness of the solutions of individual translators as at registering the fluctuations or increase of quality in a given aspect of the poem’s poetics. The overimposition of these provides a resultant showing the overall adequacy of translation at the particular points of the series’ development. The aim of the survey is not to discover how Eliot’s early signature poem has been interpreted by the successive Polish translators, but rather to test a certain (set of) assumption(s) about translation series as such. With this in mind, only a brief repertoire of features will be analysed and some aspects will not be given a full discussion but instead the results of it will be summarised.

The Polish Prufrocks

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock30, the piece considered to have ushered in modernist poetics, was written in 1911 and published in T.S. Eliot’s first collection of verse, Prufrock and Other Observations, in 1917. The Polish reception of Eliot began in the 1930s, with only five poems (Prufrock not among them) translated and published in periodicals by the poet Józef Czechowicz31. The Second World War prevented any wider cultural influences from the Anglo-Saxon culture, and later, in the Stalinist period, there were ideological barriers to the reception of a poet so intellectual, so religious, hermetic and conservative. A handful of poems appeared in literary magazines, including a 1948 translation of the Love Song by Władysław Dulęba32, which gained a greater resonance only when reprinted in Eliot’s first Polish collection in 196033. The second rendition, by Michał Sprusiński, dates to 1978, appearing in a collection of totally new texts34. Until the 1990s these two translations remained the only available Polish versions of Prufrock – at least in practical terms35. The successive three appeared within a decade and can be considered a synchronic segment of the series. Adam Pomorski first published his proposition in 1993 and it later came to open his comprehensive presentation of Eliot’s poetry36. Stanisław Barańczak followed in 199837. The latest version comes from Krzysztof Boczkowski (2001), who has been returning to Eliot throughout the past forty years. This text was reprinted in 201338 and 2016, therefore also in the sense of circulation it remains the “last say” so far.

1. Phonoaesthetic qualities

It seems appropriate to begin the survey with phonoaesthetic qualities because in The Love Songof J. Alfred Prufrock it is rhythm that organises the succession of images and thoughts, and sound correspondences often prove striking. Marjorie Perloff argues that what was most arresting in 1917, and remains most attractive for the modern reader, is the way the poem sounds39. She goes on to show subtle assonances and echoes in the opening lines of the poem and to prove that they are brought about by deliberate careful word choices40. Joan Fillmore Hooker in a specifically translational context stresses that re-creating the sound and rhythm is a sine qua non of achieving equivalence with Eliot’s original41.

In this area the two earliest Polish renditions score lowly: while there are passages that show rhythmical patterns, some longer stretches of text are not cadenced at all. This is particularly the case with Władysław Dulęba’s text, confirming Magdalena Heydel’s observations about his translation of Gerontion42. Michał Sprusiński employs specific pulse patterns at times, but alongside passages that sound flat and very prose-like. Lines quoted further in the paper will not infrequently show insufficient regard for rhythmic organisation.

Unlike in the original, where echoes, alliterations and internal rhymes permeate the text, in the two first Polish versions they remain incidental. The rhymes are mostly imperfect or approximate, they are re-created in the first two stanzas and in the “Michelangelo” couplet, and then appear only occasionally. Dulęba and Sprusiński seem not to have been aware of the essential character of musical qualities of Eliot’s poem. As Heydel justly remarks43, some defects of early Polish renditions of Eliot were due to the lack of access to the wider, active context of the 20th-century poetry of the English language, enforced by the Iron Curtain; inability to understand the phonic organisation of this poetry may have belonged to such issues.

The later translations are musicalised to a much greater extent. Adam Pomorski re-creates the sound-structure of The Love Song in a masterly way, with identifiable rhythms, numerous rhymes, occasional internal echoes. At times he even amplifies the rhyming scheme, which can be judged a compensatory gesture, seeing that rhymes in Polish are (or used to be) much more important and prominent than in the Anglo-Saxon tradition. The sound of Śpiew miłosny J. Alfreda Prufrocka bears out Jean Ward’s opinion that Pomorski’s translations from Eliot are faultless with respect to rhythmical qualities44. Stanisław Barańczak, the acclaimed poet-translator, considered the master of form and known for almost breakneck stunts in re-creating versification, is also highly attentive to musicality. He builds a rhyme scheme and internal echoes, yet does not enhance this quality of Eliot’s poem. These two translators introduce as well certain sound correspondences comparable with the original euphony. Importantly, they achieve the phonic equivalence without falling into the trap mentioned by Umberto Eco: of sweetening what was meant to sound acrid45. Krzysztof Boczkowski is well aware of the intricacies of Eliot’s versification, as proved by his comment drawing the readers’ attention to the only segment where the poet altogether refrained from rhyming46. Consistently, rhymes feature in this translation and Boczkowski employs some rhythmic organisation, yet less skilfully than Pomorski or Barańczak. Moreover, his solutions can be banal (and not in places where Eliot is intentionally kitschy), e.g. in the poem’s coda featuring the singing sirens he twice uses a hackneyed pair: wdal – fal (‘away’ – ‘of waves’).

The strophe comprising lines 99–110 (beginning with “And would it have been worth it, after all, / Would it have been worth while”) typifies sound patterns in particular texts. Where Eliot relies more on verbal iterations than on actual rhyming, Pomorski offers a scheme even overmarked, with an added internal rhyme (“To nie to, o co mi szło,” l. 109) and only one unrhymed verse (l. 107, E):

I cóż by koniec końców z tego przyszło nam, A

Cóż z tego w rzeczy samej, B

Z zachodów słońca i z podwórek, i z wodą spłukiwanych bram, A

Z powieści i z herbaty, i z sukien w powłóczystym stylu – C

Z tego i jeszcze z rzeczy tylu? C

Rozum wszystkiego nie ogarnia! D

Jeżeli nawet schemat nerwów rzuci na ekran latarnia: D

Cóż nam z tego w rzeczy samej, B=

Skoro moszcząc poduszkę czy zrzucając szal, E (asson. with A)

Zwrócona w stronę okna, powie, kręcąc głową: F

„To nie to, o co mi szło, g-g

Nie to, daję słowo” (Pomorski, l. 99–110). F

In the same segment Barańczak uses two full rhymes, two tautological ones and leaves three line-ends unpaired, while Boczkowski resorts to a tautological rhyme once, thus achieving three rhymes altogether. Both Dulęba and Sprusiński employ only two rhyming pairs in this strophe, the same ones: ulicach – spódnicach and szale – wcale, solutions suggested by the lexical contents of the poem itself (cf. “streets,” “skirts,” “shawl,” “at all”).

With irregular dispersion in the poem, rhymes may easily be compensated in translation in different positions. However, it seems important that the couplet “In the room the women come and go / talking of Michelangelo” (ll. 13–14, 35–36) retained its intentionally clumsy, doggerel rhyme. Dulęba, Sprusiński and Pomorski managed to preserve the name of the artist in the line-end and to find for it unobtrusive matches. The first translator retains the peripatetic character of the conversation (“W salonie, gdzie kobiet przechadza się wiele”), whereas Pomorski achieves the maximal naturalness of the target-language phrase: “Panie w salonie rozprawiają wiele / O Michale Aniele” (‘Ladies in the drawing room debate Michelangelo extensively’). Barańczak, while offering a strong assonance, changes the segmentation of the phrase, dividing it into three verbless sentences:

W salonie – panie, pań, paniami, paniom.

Konwersacja. Temat: Michał Anioł. (Barańczak, l.13–14)

The repetition of variously inflected plural noun panie (ladies) creates a shortened and reshuffled declension paradigm, a device which in Polish suggests a recurrence of a topic. In this way women themselves become the subject of the talk, which is referred to by the Latinate noun konwersacja (rather than the native and neutral rozmowa). The couplet remains ironic towards the assumed elegance of the salon, but its form becomes much more sophisticated. In fact, Barańczak’s option is the most caustic one – an asset if one realises the irony inscribed in the rhyme which presupposes an Anglicised pronunciation of the painter’s name47. On the other hand, the sophistication is not necessarily a desirable characteristic in the lines meant to suggest a meaningless talk48. As for Boczkowski, he introduces only a weak echo: panie – Anioł. Both his and Barańczak’s move may have been motivated by avoidance of solutions already used by their predecessors.

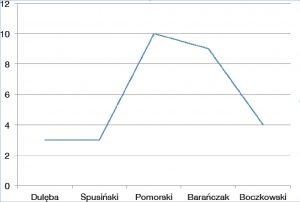

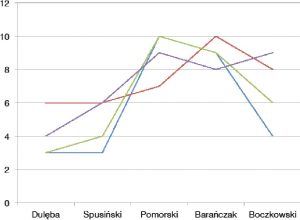

The observed characteristics can be summarised as in Table 1 below, which transposes the discussed translational choices into an arithmetical score. If the results are then plotted in a line chart, they illustrate fluctuations of this one facet of the poem’s poetics in the analysed Polish series. The musical quality of Eliot’s voice peaks with the third and fourth rendition.

Table 1. Re-creation of musical qualities of the verse in the particular translations

|

Components |

Translator |

||||

|

Dulęba |

Spusiński |

Pomorski |

Barańczak |

Boczkowski |

|

|

rhythm (x2) |

– |

– |

++ |

++ |

+ |

|

rhymes |

0,5 |

0,5 |

+ |

+ |

0,5 |

|

‘M.’ couplet |

+ |

+ |

+ |

0,5 (sophistication) |

– |

|

sound effects |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

0,5 |

|

Score: _/10 |

3 |

3 |

10 |

9 |

4 |

Note on the tables: in all sections the score will be calibrated as “out of ten” to make possible the final overimposition of particular results on a chart with one scale.

+ means a fully successful re-creation in the target text

(x2) – a crucial element given double weight in the calculation.

Chart 1: Phonoaesthetic qualities in the surveyed series

2. Thematic core: Uncertainty and indecision

Most scholars and readers of translations would probably agree that the thematic core of a given text is part of any translation invariant and a factor of translation quality. In the case of The Love Song uncertainty and indecision constitute the thematic vein of the poem, with Prufrock’s reluctance or inability to ask the “overwhelming question” from ll. 10 and 93. The theme also penetrates into the poetics of the dramatic monologue, inasmuch as the way in which it is written in many respects itself communicates and discloses the persona’s predicament. Selected excerpts will serve investigating how the translators deal with this.

Uncertainty, the “deliberate theme” of the whole 1917 collection,49 is brought to the fore in the famous first stanza of its first poem. The instability of the speaker’s self is represented in the splitting into “you and I.” This, dédoublement of the persona in the manner of Laforgue, self-ironically expresses the speaker’s struggle with his own self50. The initial formulation is maintained in all the renditions, but the further references to “you” have caused some translational difficulties. In this very stanza, Dulęba unnecessarily employs the emphatic accusative form ciebie – instead of the short cię – which implies that the person “led on” to the overwhelming question is an actual second character51. Later on the same translator inserts the pronoun (ty) in a context that in Polish demands its skipping:

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet (l. 26–27).

I będzie czas, i będzie czas,

Bym przygotował twarz

Na spotkanie tych twarzy, które ty widujesz (Dulęba, l. 26–28).

Eliot’s “you” here is apparently the English pronoun meaning ‘people in general’, ‘one’. The overliteral translation unnecessarily renews the distinction between “I” and “you,” and by emphasis implies that they have a different social experience. Apparently, for Dulęba, there are actual two people paying the visit. To compare, Sprusiński’s version, although still quite literal, sounds grammatically acceptable for a man talking to himself: “na spotkanie twarzy, które spotkasz” (“you” is implicit in the 2nd-person verb spotkasz).

Pomorski, in turn, pursues Eliot’s device even further. His Prufrock occasionally refers to himself using the second person plural, which proves a successful way of conveying self-irony. Thus, “With a bald spot in the middle of my hair” (l. 40) becomes especially effective as “Bo łyse plamy w swoich włosach mamy” (‘Because we’vegot bald spots,’ note the internal rhyme, too), and “Would it have been worthwhile…?” (l. 99) is rendered as “I cóż by… z tego przyszło nam?” (‘And what good for us would have come of that?’).

Indecision looms in the mantra “There will be time.” The predicament itself is invoked verbally in the following passage and underscored by the enumerations and sound repetitions:

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea (l. 32–34).

Prufrock’s aboulia is reproduced in all translations, but with a varied degree of artistry. In Dulęba’s translation, the fragment belongs to the most felicitous ones:

A przecież czas na sto niezdecydowań,

Na sto spostrzeżeń i sprostowań,

zanim podadzą herbatę (l. 33–35).

The three nouns, semantically appropriate (while not literally copying the source text), echo each other closely. The text generates a slight estrangement effect, because the abstract noun ‘indecision’ – niezdecydowanie – sounds unaccustomed when used in plural in Polish. Even though the original time-adverb “yet” is unnecessarily treated as the conjunction of contrast (przecież), which proves Dulęba’s somewhat insufficient understanding of the text, it remains clear in his rendition that Prufrock is postponing a decision.

Sprusiński’s version proves the one least satisfying phonically and this fragment illustrates my earlier claim of rhythmical deficiencies of his text. Moreover, the word choices are not echoed in the successive stanza (Eliot’s “In a minute there is time / For decisions and revisions,” l. 47–48). Decyzje do not reiterate the sound of niepewności – the latter pair of lines is clasped together by a near rhyme, but not linked in a pattern with the former set:

Jeszcze czas na sto niepewności,

Sto objawień i poprawek,

Zanim podadzą tost i herbatę (Sprusiński, l. 32–34).

Oto jest czas w minucie

Decyzji i poprawek, które minuta odwróci (l. 47–48).

The three later translators try to emphasise the paralysis of will by additional devices. Pomorski profiles Prufrock’s indecision by deploying the verb uchylać się (to evade, dodge), with the ‘hundred decisions’ as the object. In the following line, he applies inversion, putting the numeral in postposition: wizji stu (‘visions hundred’).

Czas mój i twój, czas na to,

Żeby uchylić się od stu decyzji,

Od wizji stu i stu rewizji

W oczekiwaniu na grzankę z herbatą (Pomorski, l. 31–34).

Barańczak conveys hesitancy by means of formulations perceptibly broken off (l. 32: ‘time for you to; time for me to’ – compare Eliot’s “Time for you and time for me,” l. 31). Then he reduces indecisiveness to absurdity by having Prufrock admit that he may change his mind even at the sightof (na widok) toasts and tea:

Czas, abyś; czas, abym; czas na to

Nie kończące się niezdecydowanie,

Na to, by mieć coś w planie, lecz wciąż zmieniać zdanie,

Nawet na widok grzanek i filiżanek z herbatą (Barańczak, l. 32–35).

Boczkowski counts hesitations in thousands (tysiąc) rather than hundreds and gives the stanza a strong closure thanks to a paronomasia joining “tea” with “biscuit” (herbata – herbatnik), the latter replacing the source-text’s “toast”:

I czas na tysiąc wahań wśród decyzji,

Na tysiąc wizji oraz ich rewizji,

Nim po herbatnik sięgniesz i herbatę (Boczkowski, l. 31–34).

In Prufrock’s voice indecision couples with self-consciousness and shyness, as shows the recurrent phrase “Do I dare,” complemented in a most metaphysical or most mundane ways: “Disturb the universe?” (l. 46), “to eat a peach?” (l. 123). Another signal of self-doubt is the question “(how) shall I presume” (ll. 54, 61, 68). The key phrases reappear in all Polish versions. Three translators resume the lexical variation of “dare” and “presume.” Sprusiński and Barańczak harness two reflexive verbs, ośmielić się and odważyć się, if not necessarily following the source-text pattern of distribution (cf. Table 2). Pomorski adheres to one lexical basis, but juggles with two verbs: śmieć, ośmielić się, and the verbal phrase zdobyć się na śmiałość (‘dare – have the nerve to – pluck up courage’). Dulęba and Boczkowski consistently apply just one verb in all the contexts connected with this motif, which, in turn, enhances the intratextual coherence. It can therefore be said that both kinds of translational behaviour contribute to maintaining quality.

Table 2. Expressions of self-consciousness in particular translations

|

Phrase Translator |

Do I dare |

Do I dare |

(How) should I presume? |

|

Dulęba |

Czy ja się ośmielę |

Czy ośmielę się zjeść |

Jakże się więc ośmielę? |

|

Sprusiński |

Czy się ośmielę |

Odważyć się brzoskwinię |

Jakże się więc ośmielę? |

|

Pomorski |

Czy się ośmielę ład |

Przedziałek śmiałbym […]? |

Jakże się na śmiałość |

|

Barańczak |

Czy się odważę |

A jak będzie z jedzeniem brzoskwiń? |

Jakże się więc ośmielę? Jakże się więc odważę? |

|

Boczkowski |

Czy się ośmielę |

Czy brzoskwinię zjeść się ośmielę? |

Jakże się więc ośmielę? |

The attempted assertiveness constantly gets undercut. In line 80 Prufrock ponders if he could brace up and “force the moment to its crisis,” i.e. make a decisive move in his relationship. Three translators, Dulęba, Sprusiński and Boczkowski, talk about “overcoming a moment’s weakness.” While the overall result remains the same – strength is not gathered and Prufrock does not “presume” to put in his question – a significant departure from the original consists in implying that inability to act is a momentary, not a permanent state for the speaker:

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis? (l. 79–80)

Czyżbym teraz, po herbacie, po ciastkach i lodach

Znalazł siłę, by przemóc chwilę tej słabości? (Dulęba, l. 82–83)

Czyżbym po herbacie, keksach, lodach

Miał siłę przemóc ten słabościmoment? (Sprusiński, l. 79–80).

Czy po herbacie, lodach, pośród gości,

Będę miał siłę, by pokonać moment swej słabości? (Boczkowski, l. 79–80)

Pomorski avoids showing listlessness as a thing of the moment. His Prufrock asks rhetorically who, in such circumstances, could not give way to weakness. However, his formulation is – unusually for this rendition – awkward, involving ‘bowing/taking one’s hat off to weakness’ (przed słabością… uchylić czoła):

Któż po herbacie, lodzie i ptifurkach zdoła

Oprzeć się, przed słabością nie uchylić czoła? (Pomorski, l. 79–80)

Only Barańczak finds an idiom that means bringing matters to a head. Interestingly, the phrase literally translates back as “putting an issue on a knife’s blade,” which builds wordplay with the previous line, featuring – in this rendition – another piece of cutlery, a teaspoon (łyżeczka), and the action of putting it down:

I teraz, gdy łyżeczkę na spodeczek złożę,

Miałbym postawić rzecz na ostrzu noża? (Barańczak, l. 80–81)

[Now, having put the teaspoon down on the saucer,

Should I bring matters to a head / Should I ‘put the issue on a knife’s blade’?]

Finally, there is one more side to Prufrock’s frustrated (inter)actions: his inability to communicate. Having refused to act and having analysed this decision, the speaker finds himself speechless. His recognition of this is rendered as follows:

It is impossible to say just what I mean! (l. 104)

Nie potrafię wyrazić mych myśli! (Dulęba, l. 108)

Nie potrafię wyrazić ściśle, co myślałem, (Sprusiński, l. 104)

Rozum wszystkiego nie ogarnia! (Pomorski, l. 104)

Nie wiem, jak to powiedzieć… nie, nie jestem w stanie! (Barańczak, l. 105)

O co mi chodzi, wyrazić nie jestem w stanie! (Boczkowski, l. 104)

Four translators retain this important aspect of Prufrock’s condition, while giving it different shades. Dulęba’s option suggests a possibility of a generalised reading in ‘I can’t say what I think’ (although the verb used is a perfective one, wyrazić, not wyrażać). Sprusiński’s persona cannot precisely express what he was thinking at a past moment and, perhaps because of this imposed time perspective, does not sound upset about it, as reflected by the change in punctuation. Barańczak, conversely, is the most emphatic, having squeezed into one line two admissions of speechlessness. Boczkowski seems closest to the original formulation. In contrast, Pomorski inserts a completely different thought. As this line ends an enumeration (see extended quote in section 1), the multiplicity of things seems too much for the subject: ‘Reason will not embrace everything.’ Untypically for this rendition, the semantic shift was effected to achieve a sound embellishment; the verb form ogarnia provides a full rhyme for magiczna latarnia (“magic lantern” in “But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen,” l. 105). To compare, Barańczak sacrifices rather the lantern, while retaining the self-expression problems as well as the disturbing “medical” image recalling the beginning of the poem – he talks of ‘projecting on a screen / a nervous system’ (l. 106–107, line-end: na ekranie, and enjambment – cf. below).

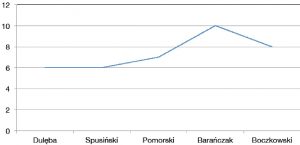

The five aspects that have been selected as touchstones for this category can be formalised as in Table 3 and Chart 2. The surveyed feature peaks in the series with Barańczak’s translation where it apparently reaches optimality. The newest translation scores high, nonetheless the curve does not remain level, let alone ascend further.

Table 3. Thematic core of indecision as represented in particular renditions.

|

Components |

Translator |

||||

|

Dulęba |

Spusiński |

Pomorski |

Barańczak |

Boczkowski |

|

|

“you and me” |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

indecision |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

“dare” / “presume” |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

“force the moment to its crisis” |

– |

– |

+/– |

+ |

– |

|

inability to communicate |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

|

Score: _/10 |

6 |

6 |

7 |

10 |

8 |

Chart 2: Thematic core of indecision as represented in the series

3. Language and poetic diction

As justly stressed by Hugh Kenner, Prufrock is primarily a voice52. Therefore, the linguistic shape of foreign-language renditions should preserve qualities of this voice and the tenor of its impossible love song. The critical impact of this dramatic monologue relied on its colloquial idiom and distinct oral character, on the immediate perception that it was written “in a language remote from established poetic diction,”53 to use Thomas Kinsella’s formulation.

A quality translation would presuppose a similar poetics: introducing into the target texts colloquial language and idiomatic speech. Conversely, breaches of idiomaticity are undesirable – as noted already by Wacław Borowy54, one finds Eliot’s formulations strange, yet not awkward. The discussion of this aspect is complemented by several more examples in Table 4.

Dulęba cast his version in a language rather neutral and standard (for his time) than colloquial. For instance, he calls a “sawdust restaurant” from l. 7 restauracja, while other translators prefer the expressive noun knajpy – ‘joints.’ The yellow fog in the second stanza (l. 16–17) has a muzzle (morda), but for its tongue Dulęba chooses the neutral word język, where, again, his successors opt for more marked solutions. He renders the imagined comment on the thinness of Prufrock’s limbs with the use of the elegant verb zeszczupleć, whereas later versions feature the more direct schudnąć (or the adjective chude). Occasional high-register choices in the earliest translation include the archaic particle zaiste (‘forsooth’ – bookish but not Biblical), and ronić – an equivalent for “dropping” (the question on the plate, l. 30) that is nowadays labelled by dictionaries as poetic55. Possibly neither stood out so much in 1948, but on the whole, Dulęba’s language sounds more formal than the original voice. On the other hand, the diction is undermined by some awkward words or expressions, like the collocation pościłem znojnie (‘I fasted in toil’). There even appears a notorious erratic form: the singular perfuma (for “perfume from a dress,” l. 65) might have been used with ironic intent, yet sounds incongruent with the speaker’s otherwise educated voice. In some cases one should make allowances for the diachronic changes in language. Still, rozdział for a parting in the hair might have been old-fashioned already then56 and now amuses, as the noun primarily denotes a ‘chapter.’

Sprusiński achieves slight colloquiality, e.g. in the infinitive-based questions (with interrogative particle elided) as in “Odważyć się brzoskwinię zjeść?” (“Do I dare to eat a peach?,” l. 122). However, the effect is undermined by his use of elements of elevated language. The recurring conjunction albowiem (compare: “For/And I have known,” ll. 49, 55, 62), and the verb wdziać for ‘putting on’ trousers seem far too solemn. Another heightening of tone is triggered by a change in imagery: for the rhyme’s sake wreathes woven by the mermaids become diadems. There is also a questionable collocation, “rozpięty na szpilce,” in one of the memorable images – that of the eyes that pin down (discussed below).

Jerzy Jarniewicz notes with approval what he calls the “demotic” Polish of Pomorski’s translations from Eliot57. In The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock Pomorski’s diction proves, indeed, colloquial and very idiomatic, with numerous fortunate collocations, the use of diminutive in the word chwilka (a short moment) or the syntactic choice reflecting “I am no prophet” – żaden ze mnie prorok (l. 83). Felicitous solutions much outnumber the single dubious – catachrestic – formulation.

Barańczak uses language equally or even more flexible and rich. The natural inflections of colloquial Polish are manifest e.g. when “and here’s no great matter” (l. 83) becomes the nonchalant parenthetical (nie żeby mi zależało) – ‘not that I care much.’ The only reservation concerns the expression w ogóle i w szczególe, which is idiomatic but seems too low in rendering the quantifier “all” in the lines: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead, / Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all” (l. 94–95). Lazarus is, after all, a role rehearsed by Prufrock yet rejected as too sublime; Barańczak’s choice seems to question this sublimity.

Boczkowski begins in a neutral style. However, he shows an inclination to step into a higher register unnecessarily. For instance, he translates “I am” into a markedly archaic and solemn compounded form jam in all three “I am” statements (“Lazarus,” “no prophet,” “not Prince Hamlet,” ll. 83, 94, 111). There are also examples of very convincing, natural formulations, yet it is only fair to note that some of them are repeated after Barańczak with minimal changes in grammar and order (example in Table 4). Instances of unnatural collocations happen. This version also occasionally lacks punctuation marks demanded by the Polish syntax, e.g. in the “Michelangelo” couplet or in the last two tercets. This is not a strategic dismissal of punctuation – as happens in modern Polish poetry often enough or as is done more consistently by Sprusiński in his translation – because the comma appears or is elided in comparable contexts, e.g. before an attributive clause: “głosy które milkną” vs. “oczy, co mnie utrwalą” (ll. 52, 56).

Table 4. Characterisation of diction employed in the translations

|

Translator |

level of colloquiality and idiomaticity examples |

awkward or inappropriate |

|

Dulęba |

neutral: restauracja, język, zeszczupleć |

pościłem znojnie (‘I fasted in toil,’ wrong collocation) |

|

Sprusiński |

slightly colloquial: |

albowiem (high-register conj.) |

|

Pomorski |

colloquial and very idiomatic: |

suknie w powłóczystym stylu |

|

Barańczak |

colloquial and very idiomatic: |

w ogóle i w szczególe |

|

Boczkowski |

neutral, moderately idiomatic: |

łzy wzajemne (‘reciprocal tears,’ wrong coll. with no corresponding ST unit) |

The style of The Love Song is predominantly colloquial, nonetheless there are changes of tone. As a result, in some segments a heightened register will be legitimate or even desirable58. For instance, Barańczak’s lexical choice adwersarz (adversary) does not impose false diction when it metonymically represents the equally sophisticated “insidious intent” (l. 9). Most conspicuously, however, in the poem’s coda the speaker switches from self-mockery to an almost romantic diction of longing:

I have seen them [mermaids] riding seaward on the waves

Combing the white hair of the waves blown back

When the wind blows the water white and black (l. 126–128).

The tercet voices the lyrical intensity which remains unattainable for Prufrock himself, something that he can only imagine at a distance. All translations reflect the shift of tone, yet the turn from the common to the poetical is most powerfully expressed by Pomorski, who applies a convoluted (while fully readable) Latinate syntax, that in Polish was used in Renaissance poetry:

Na falach, w morze, widziałem, pędziły,

Przeciwnej wichrząc białe włosy fali;

Toń biało-czarną wiatr podnosił z dali (Pomorski, l. 126–128).

Compare regular word-order and the normally required conjunction (‘I saw how they were speeding’):

Widziałem, jak na falach pędziły w morze,

Wichrząc białe włosy przeciwnej fali;

Wiatr podnosił z dali biało-czarną toń.

Especially striking are the inverted position of the main-clause verb, widziałem (‘I have seen’), and the splitting of the epithet from the noun in przeciwna fala (‘blown-back wave’) by putting a whole participial phrase in between. This local strategy parallels remarkably well a characteristic of Eliot’s early poems, namely the influence of French on his syntax and choice of expressions. While such an affinity is sometimes believed to facilitate translation into French59, it can hardly be conveyed in other languages, at least without causing affectation. Pomorski’s subtle Latinisation seems to compensate this masterfully.

Eliot’s unmistakable poetic voice is further defined by novel phrasings and imagery, challenging the post-Romantic clichés and intentionally disturbing. The lines evoking the threat of the “fixing” regard of others provide a representative example worth checking across the translations. Jean Ward notes that the two earlier versions do not fully convey the cruelty of the original image60. A comparison with the original bears out her claim:

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin (l. 56–57).

Oczy, co cię utwierdzą w ułożonym zdaniu,

I skoro jestem przytwierdzony, przybity szpilką (Dulęba, l. 59–60).

Oczy co cię utrwalą w formułce zdania,

I gdy jestem nazwany, rozpięty na szpilce (Sprusiński, l. 56–57).

Dulęba plays on two related verbs meaning ‘confirming’ and ‘fixing to something’ but, admittedly, utwierdzać carries rather positive connotations. Sprusiński’s choice of utrwalać reverberates semantically with cementing and smacks of being ‘preserved’ in formalin, but also has a positive value due to such dominant meanings as ‘making something durable,’ or ‘committing to memory’61. Still, the eyes are not profiled as the agent in this rendition. The effectiveness of Sprusiński’s rendition is also limited by the awkwardness of the phrase rozpięty na szpilce (illogical: ‘spread out / stretched on a pin’).

The nexus of the literal and the figurative meaning on which Ward insists62 is certainly achieved by Pomorski:

Gdy patrzą, jaką by mnie przyszpilić formułką,

A kiedy sformułują, nabiją na szpilę (Pomorski, l. 56–57).

The eyes ‘pin down’ by means of formulas, it is indisputably they that inflict pain. The effect is strengthened by the related noun-verb pairs: szpila – przyszpilić, formułka – formułować, which themselves seem to form a “net” catching the subject-insect. It is also strikingly appropriate that Pomorski employs the diminutive formułka, a disparaging word in Polish, alongside the augmentative szpila, which conceptualises the pin as bigger and hence more painful, and besides, figuratively evokes malicious remarks.

Barańczak, in turn, de-automatises reading by playing upon the accustomed phraseology with ‘eyes closing’ – here they enclose the speaker, though. The subject gets imprisoned in the formula, assigned a number (as would happen to an exhibition object), and only then the image of being pinned down and therefore immobilised follows:

Oczy, które mnie zamkną w gotowej formule,

I co wtedy? Gdy zamkną, numerkiem oznaczą,

Gdy, przyszpilony, już nie będę mógł uciekać (Barańczak, l. 56–58).

Boczkowski goes back to Sprusiński’s utrwalać, a verb judged not powerful enough by Ward, and buys an end rhyme (formule – szpikulec) by having Prufrock imagine himself driven on a pointed stick rather than on a pin:

Oczy, co mnie utrwalą w utartej formule,

A gdy mnie przeszywając wbiją na szpikulec,

Gdy przyszpilony wiję się na ścianie (Boczkowski, l. 56–58).

The usual referent for szpikulec is a skewer or spit, an implement bigger than those used for fixing an insect or worm. Przyszpilony, the passive participle for ‘fixed/pinned down’ in the next line (cf. orig. “When I am pinned”), does not sound logical, since a skewer would entail the state of being ‘stuck’ and a different verb. These flaws dilute the oppressiveness, and the image remains captured best by Pomorski and Barańczak.

Naturally, this single fragment could not on its own be a measure of the success of the respective translations in representing Eliot’s specific use of imagery. Yet the chosen example is quite representative of the surveyed target texts in that respect. It could not be said that any of the translators disregards the original poetics, yet Dulęba and Sprusiński occasionally take off the edge of Eliot’s striking wording. Barańczak re-creates the ultimate sense of the image while often, as was his wont in general, does not hesitate to introduce a new micro-image (like here) or to de-automatise reading by his favourite enjambment (see e.g. l. 106–107 referred to in section 2 and l. 29–30 cited in section 4). Boczkowski frequently earns his rhyme scheme at the cost of substitutions (as here) or amplifications, which at times affect the author’s diction in an undesirable way. Pomorski often – although not always – comes off best in the comparisons.

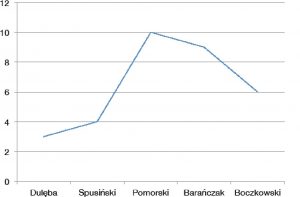

These features provide material for this section’s measurement in Table 5 and Chart 3. For concision, the conducted analysis underlying the results in the table cannot be reported in full. Examples of paronomasias – which contribute to the sound of Eliot’s voice and are taken into account – have been cited in other sections of the paper and are representative of the particular translations.

Table 5. Features of the poem’s language as represented in particular translations

|

Components |

Translator |

||||

|

Dulęba |

Spusiński |

Pomorski |

Barańczak |

Boczkowski |

|

|

colloquial diction |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

|

idiomaticity |

– |

0,5 |

+ |

+ |

0,5 |

|

appropriateness |

+ |

– |

+ |

0,5 |

+ |

|

capturing imagery |

0,5 |

0,5 |

+ |

+ |

0,5 |

|

paronomasias |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Score: _/10 |

3 |

4 |

10 |

9 |

6 |

Chart 3: Language characteristics in the surveyed translation series

4. Intertextuality

Intertextual references are crucial for the poem and typical of Eliot’s peculiar diction, abounding in subtle and fragmentary signals of dialogue63. In The Love Song their use characterises the speaker as an educated man, but they also serve his direct self-representation. Beginning with the epigraph, intertexts influence the readers’ expectations, activate contexts and interpretive frames.

From the tight web of allusions, a selection of eight will be surveyed. They represent varied spheres of reference and still form a wide grid. Since successful rendering of intertextuality consists not in achieving a formal correspondence of markers but in conveying their pragmatic implications, in the case of Eliot’s cryptic allusiveness, additional means like the use of explanatory notes for target texts will also be considered (if such a paratext comes from the translator and not a later editor).

All the five translators retain the epigraph which by recalling Inferno’s Guido Montefeltro evokes the concepts of being trapped in hell, of secrecy, of duality. They supplement it by attribution and a quote from Edward Porębowicz’s canonical Polish rendition of Dante’s epic.

As for the intertextual signals in the body of the text, the most legible of them reappear in all translations. When Prufrock declares that he is “no prophet” despite having seen his “head upon the platter” (l. 82–83), the allusion to John the Baptist remains clear in all renditions, the varied lexical choices for the “platter” (półmisek, taca, misa) notwithstanding. The reference to Lazarus (l. 94) did not cause difficulties either. The speaker’s self-representation is completed by another negative juxtaposition – with Hamlet. Instead, he compares himself to “an attendant lord,” “almost the Fool” (ll. 112, 119). In Dulęba’s and Boczkowski’s versions a characteristic is not appropriate for Polonius (featuring in only a few scenes, rather than opening them, cf. “start a scene or two,” l. 113), but other clues make it fully possible to identify the character. Descriptions in all other renditions evoke Polonius as well.

The motif of mermaids (l. 124) should also be easy to handle, yet only three translators employ the noun syreny which denotes the mythological creatures. Dulęba writes about ‘the singing of drowned women /water demons’ (śpiewy topielic, l.130). The context of an alluring call evokes the Sirens, but the lexical choice, oriented on achieving a near rhyme (flaneli – topielic), is not fortunate. Pomorski, strangely, chooses a hypocoristic, syrenka (l. 124), which associates with children’s fairy-tales and thus decreases the seriousness of the passage. This surprises vis-à-vis his majestic rendering of the description of mermaids riding seawards (cited in section 3) and the endnote64 where Pomorski cites as a possible context Donne’s Song (in Barańczak’s translation, containing the non-diminutive form Syreny).

Lines 28–29 bring together two allusions, a biblical and a classical one. Especially the latter proves inconspicuous, embedded as it is in the poet’s own phrase:

There will be time to murder and create

And time for all the works and days of hands (l. 28–29).

Będzie czas, by zabijać i tworzyć,

Czas na działanie i czas rąk,

Które […] (Dulęba, l. 29–31).

Czas zabijania i tworzenia,

Czas pracy i czas dłoni (Sprusiński, l. 28–29).

Czas zabijania i czas płodzenia,

Prac i dni wszystkich czas nastanie (Pomorski, l. 28–29).

Nastanie czas na mord i czas na tworzenie, nastanie

Czas na prace i dnie ludzkich rąk (Barańczak, l. 29–30).

Będzie czas zabijania oraz czas tworzenia

I czas na dni i prace (Boczkowski, l. 28–29).

The source-text phrase “There will be time to murder and create” (l. 28) only distantly echoes Eccles. 3:3 (both King James Bible65 and American Standard Version66 have: “There is… A time to kill, and a time to heal”). Nonetheless, the context of Eliot’s whole enumeration naturally suggests the Preacher’s “time to every purpose.” In Polish, whether the phrase will be perceived as a Biblical one depends on the grammatical structure used: the word czas (‘time’) must be followed by a nominal phrase, a gerund in genitive (‘time of doing something’). Dulęba uses the structure with a clause of purpose – ‘time to do.’ Sprusiński’s version does echo the Polish Bible, which renders the phrase paraphrased by Eliot as “czas zabijania i czas leczenia,”67 with the said gerundial structure. Boczkowski, with the same lexical and structural choices, enhances the effect by falling back on Ecclesiastes for the repetition of the noun czas (time): “czas zabijania oraz czas tworzenia” (l. 28). Pomorski follows the Biblical structure but interprets “creating” as “producing” in the sense of ‘breeding’ – this move does not undermine the link of the line with its pre-text, yet it narrows down the senses inscribed in it in Eliot’s receiving text. Barańczak’s solution is the reverse: lexically, he follows Eliot rather than the Bible and talks of ‘murder’ (alongside ‘creating’), whereas his choice of a prepositional syntax hardly evokes the Biblical echo for the target reader.

The allusion to Hesiod’s title Works and Days was preserved by Pomorski and Barańczak. Boczkowski reversed the order of the nouns (dni i prace) for the sake of rhyme (prace – tacę) and provided explanation of the intertextual link in an endnote68. The inversion makes it very difficult for the reader to notice the intended reference if unaided; therefore the use of the paratext becomes a remedy against the blurring of the signal. On the text level, however, the allusion cannot be considered successfully re-created. As for Dulęba and Sprusiński, they both omitted “days” altogether, and conceptually joined work (or in the former’s case even “action”) immediately with the “hands” (ręce / dłonie), indeed important for the imagery, for they are about to drop the fatal question on Prufrock’s plate…

An allusion to a classical title, if only rendered in accordance with the target-system tradition, has every chance to be recognised by an educated foreign reader. However, a reminiscence from English metaphysical poetry is much less likely to resonate for a Polish recipient. This proves true when Eliot’s phrasing recalls that of Andrew Marvell:

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it toward some overwhelming question (Eliot, l. 92–93)

Let us roll all our strength, and all

Our sweetness, up into one ball (Marvell, l. 41–42)69.

The allusion is not preserved by Dulęba. Admittedly, when he translated the poem, no Polish version of To His Coy Mistress was available. Still, his use of the word gałka (‘knob’) suggests that he was not conscious of the presence of the reference:

Ściskać wszechświat do rozmiarów gałki

I toczyć ją do nieodpartych pytań (Dulęba, l. 96–97).

Sprusiński’s Prufrock also talks about moulding into a knob (“Zgniatanie wszechświata w gałkę, / Aby go toczyć w pytania nieodparte”), although by the time of his creation, a translation of Marvell’s poem, by Jerzy S. Sito, had appeared. In this 1963 text the relevant lines read: “Tedy Moc całą, Chęć i Słodycz wszelką / Utoczmy razem w jedną kulę wielką”70). Sprusiński indicates the source of allusion in his afterword71, yet the only point in common between the two Polish excerpts is the verb

(u)toczyć, anyway suggested directly by the source texts. When both Dulęba’s and Sprusiński’s translations were reprinted in the 1990 critical edition of Eliot’s works, no connection with the metaphysical poem was indicated by the editors, which suggests that in Poland even scholars perhaps remained little aware of the intertextual importance of this line. It is Pomorski who introduces into the series the motive of ‘rolling a ball.’ He creates a verbal echo between his formulation in Eliot’s poem and the distich from Marvell which he quotes in an endnote in, apparently, his own rendition:

Że małą kulkęutoczywszy z globu,

Do przygnębiającego turlasz ją pytania (l. 92–93).

Tę słodycz, co w nas wzbiera czule,

I moc utoczmy w jedną kulę (Marvell, Do pani cnotliwej)72.

Stanisław Barańczak is in a unique position in this case, because he himself translated To His Coy Mistress. When rendering Prufrock, however, he has not made the reverberation between the two texts especially prominent. Compare:

Wgryzać się w taką kwestię z uśmiechem, zgniatać w kulę

Wszechświat i toczyć go w stronę jakichś przygważdżających pytań (Barańczak/Eliot, l. 93–94).

Całą więc naszą moc i całą czule

Wezbraną słodycz zlepmy w jedną kulę (Barańczak/Marvell, l. 41–42)73.

The lexeme kula (for “ball”) does appear, but in the translation from Marvell the word for ‘rolling’ (toczyć) did not feature. The similarity could have been enhanced by using the verb lepić in Prufrock (from the imperative zlepmy in the Polish Marvell). However, Barańczak prefers zgniatać, which is closest to Eliot’s original “squeezing” in terms of imagery. Barańczak’s rendition of To His Coy Mistress is invoked once more in the series of the Polish Love Songs: the author of the latest version explains the reference in an endnote74, quoting Barańczak’s Do nieskorej bogdanki. Nonetheless, Boczkowski, too, employs the verbs toczyć and zgnieść (finite form) and refrains from strengthening the actual textual link:

Wszechświat zgnieść w jedną kulę

I toczyć go w kierunku ostatecznych pytań (Boczkowski, l. 92–93).

References in Eliot’s poem are as a rule of low level of explicitness75, some practically classify as covert ones. Dispersed, fragmented and de-contextualised, they may escape a foreign reader’s notice even if translated with all due diligence. Bearing this in mind, one can treat added explications of intertextual links as elements contributing to translation quality76, provided that this compensates the differences in cognitive baggage, and not exempts translators from re-creating the links. As acknowledged in Table 6, Pomorski and Boczkowski offer their recipients ample notes, many of which serve namely giving information on the sources of allusions77.

The same two translators enhance the overall intertextual aura by introducing additional markers that can be treated as compensations. In the most recent version line 49 – “Bo już poznałem wszystkie dni i nocy sprawy” – strangely resonates with the first line of Franciszek Karpiński’s late-18th-century religious poem absorbed into popular devotion: “Wszystkie nasze dzienne sprawy”78. The concurrence is admitted by Boczkowski in a note79. In fact, the solution seems motivated by searching for a rhyme to the rendition of the famous line “I have measured out my life with coffee spoons” (l. 51) – which ends with the noun phrase łyżeczkami kawy. Nonetheless, the move strengthens the allusive diction. Pomorski’s version of TheLove Song actually opens on a note familiar to Polish readers of poetry, with the first line: “Cóż zatem, pójdź ze mną.” There is no “you and I,” but instead: pójdź ze mną, ‘go with me,’ a formulation which evokes the Latin phrase Vade mecum, used as cycle title by the major 19th-century poet Cyprian Kamil Norwid80. Naturalisation in the sphere of intertextuality is often dismissed or condemned by translation scholars81. Nevertheless, such procedures with respect to Eliot, of all writers, have on occasions been praised by critics82. Given that the intertextual dimension is a very important facet of Eliot’s poetics, adding those native notes to the two Polish Love Songs should probably be appreciated rather than denounced. The remaining translators do not compensate the implicitated or lost markers by any references to source, target or third cultures.

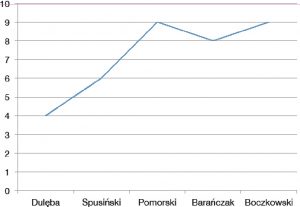

The eight surveyed markers and the two strategies give basis for the formalisation in Table 6. With this aspect, the curve in the chart comes closest to a growth curve but even in this sphere is not exactly like it.

Table 6. Re-creation of intertextuality in the respective translations

|

Components |

Translator |

||||

|

Dulęba |

Spusiński |

Pomorski |

Barańczak |

Boczkowski |

|

|

S’ io credesse |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

“time to murder and create” (Eccles 3,1-8) (l. 28) |

– |

+ |

(+) |

(+) |

+ |

|

“works and days” |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

|

head upon a platter |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

“squeezed… into a ball”(Marvell) (l. 92-93) |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Lazarus (l. 94) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

“attendant lord” |

(+) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

(+) |

|

mermaids (l. 124) |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

|

compensations |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

|

presence and reliability of paratext (translator’s) |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

|

Score: _/10 |

4 |

6 |

9 |

8 |

9 |

Chart 4: Intertextuality as reproduced in the studied translation series

Conclusions

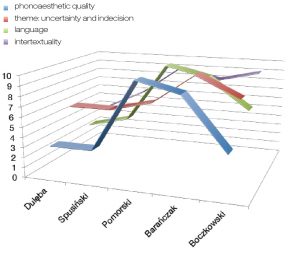

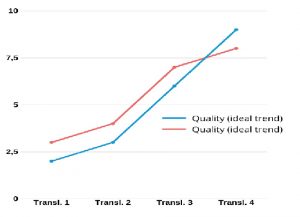

If the line charts are imposed over each other, this allows us to see the quality of renditions as a stratified phenomenon (Chart 5). It is evident that forming an assessment on basis of any single previous diagram would have been highly misleading, and that even the picture given by the four is not unequivocal. A label of overall high quality of translation can be granted only when all – or majority of – the lines run in the upper parts of the chart (as they do in the case of a hypothetical Translation 4 in an imagined ideal series in Chart 6).

Chart 5 (a & b): The four studied characteristics plotted together

Chart 6: Quality in an imagined translation series illustrating a theoretical steady growth

The translation quality projected as a bundle of aspects shows that the lines do not necessarily fluctuate in the same way. This means that development in time may – at least for this given series it does – involve an improvement in one aspect and a decrease of quality in another.

Secondly, our particular series as a whole does not show a clear progression. True, it seems to confirm that Władysław Dulęba’s translations (in general) were justly considered arduous rather than fine83. Apparently they played mainly an informative function, as pioneering ones. Michał Sprusiński’s translation was praised by Wanda Rulewicz for “being faithful to the original in the sound layer”84. This seems an excessively positive assessment in the light of the present survey, and may have been the result of partly the critic’s unawareness of some qualities of Eliot’s verse, and partly of the lack of more sonorous translations to compare. The Polish translation series of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock can be said to have peaked in quality with the versions by Adam Pomorski and Stanisław Barańczak. Or, to qualify it, to have peaked relatively, because both renditions achieve excellence in some respects at the expense of underscoring certain other studied features. As for Boczkowski, he has a good result in two fields, and a mediocre in two others. Consequently, though being the latest rendition, his text does not surpass all the previous ones as a straightforward understanding of the developmental character of a series might suggest.

Moreover, not all important aspects have been measured and projected here. In particular, it would be worth examining the renditions of The Love Song for cohesion, to see whether the internal logic is not violated by mistranslations and whether smoothing out (rationalisation) of the meandering train of thought is avoided. The more components taken into account (i.e. threads in the bundle), the greater the certainty that the assessment proves not misguided.

The charts, of course, do not constitute a method of research themselves, but a method of plotting the results. Nonetheless, I think that they show convincingly the need for a stratification of analysis and accounting for various components of quality. Still another point is that such a formalisation helps one perceive, for instance, that changes in the quality of rendering the language and those in phonoaesthetic quality have resulted in similar charts, i.e. notice a parallel which perhaps deserves a further investigation.

Finally, it seems worthwhile to revisit the conditions of improvement in quality in a series outlined at the beginning. Let us relate them to the translation series that has been discussed, with a special focus on the latest addition to it.

1. Awareness of the previous elements in the series.

In the present case, the stature of the translators, either their interest in Eliot and involvement in propagating his works (Sprusiński, Pomorski, Boczkowski) or their known practise (Barańczak), make it probable that they were familiar with the previous rendition(s). Without a translator’s direct admission it is, of course, very difficult for a researcher to establish whether they consult the existing texts during the process of composing their own. Still, this precondition can be supposed to have been fulfilled. Boczkowski, at least, admits familiarity with “previous versions”.

2. The intent to outdo the previous renditions.

On a single occasion Boczkowski openly questions decisions of his predecessors. He claims that line 88, “After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,” has so far been “mistranslated,” without naming the renditions he has in mind85. It is however, a minor point, one would say, whether “cup” is treated as a vessel or a beverage (even if the latter appears more logical here) or that marmalade is by definition a citrus product. Although, curiously enough, no key issues become highlighted in a similar polemic way, this single remark discloses an at least partly corrective intent on Boczkowski’s part.

3. Familiarity with the literary and translation criticism on the oeuvre or work.

Ward has observed that although most of the translators of Eliot are usually well-versed in the subject, this does not necessarily prevent them from overlooking certain features of poetics that scholars find crucial and worth preserving86. Boczkowski’s volume, with its undoubted display of erudition and a Prufrock that is not, artistically, the last say, confirms it.

4. Authorisation to borrow fortunate translation solutions.

Some repetitions seem necessary even in the early history of the series and dictated by the original text itself. As has been suggested with reference to the “Michelangelo” couplet, certain non-optimal solutions may also be triggered by avoidance of choices already “used up”. As for Boczkowski, he does draw on the previous versions in some respects in more obvious ways, which was pointed out on two examples in section 3: a lexical choice repeated from the second translation and the phrasing podstawia grzbiet from the third. However, this does not always prove felicitous (as in the case of the verb utrwalać).

In sum, it seems that the conditions, if not so likely, were all fulfilled. And yet, this alone did not guarantee an upward turn in the final segment of the chart. This even more strongly advises caution in perceiving a series as a development and in contributing to a series.

A b s t r a c t

The paper is an attempt to explore the interrelation between the notions of quality and seriality in literary translation. The point of departure is provided by theoretical considerations on translation series and by an expectation of quality increase to some extent inscribed in this concept. With a view to mapping quality trends in an actual translation series, five Polish renditions of T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” are surveyed. Four aspects important for the poem’s poetics are investigated comparatively and the results are then formalized. The aim is not to assess the ‘excellence’ of the target texts, but rather to map ‘quality patterns’ that can be observed in the particular aspects of poetics as the series develops.

1“E. Balcerzan, Poetyka przekładu artystycznego, [in:] E. Balcerzan, Literatura z literatury (Strategie tłumaczy), Katowice 1998, p. 18. First printed in: Nurt 1968, no. 8. All translations from the Polish criticism come from the author of the present paper.

2 “[S]eria częściowo zrealizowana, jak i potencjalna, zawsze ma charakter rozwojowy” (Balcerzan, Poetyka przekładu, ibid.). All emphases in the paper are mine.

3 A. Berman, “La retraduction comme espace de la traduction,” Palimpsestes 1990, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1–7.

4 The hypothesis has gained surprisingly unquestioning acceptance considering the rather controversial assumption that first or early translations be necessarily weak and that their weakness consists in their “acculturating” instead of “foreignising” strategy. The latter assumption has been challenged e.g. in the study: O. Paloposki, K. Koskinen, A Thousand and One Translations. Revisiting Retranslation, [in:] Claims, Changes and Challenges in Translation Studies. Selected Contributions From the EST Congress, Copenhagen 2001, ed. H. Hyde, K. Malmkjær, D. Gile, Amsterdam 2004, pp. 27–38. An attempt at changing the perspective was undertaken by Françoise Massardier-Kenney: F. Massardier-Kenney, “Toward a Rethinking of Retranslation,” Translation Review 2015 vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 73–85.

5 G. Steiner, After Babel. Aspects of Language and Translation, Oxford 1975, p. 416.

6 A very rare voice assessing seriality negatively comes from Małgorzata Łukasiewicz. Yet even she seems simply carried by her rhetorical aim of defending old(er) translations, hence her rejection of the association with a “garment that quickly falls out of fashion” and with “mass production” (M. Łukasiewicz, Pięć razy o przekładzie, Kraków-Gdańsk 2017, pp. 83–84).

7 A. Legeżyńska, Struktura serii, [in:] A. Legeżyńska, Tłumacz i jego kompetencje autorskie (1986), Warszawa 1999, 2nd ed., pp. 192–196.

8 M. Skwara, Polskie serie recepcyjne wierszy Walta Whitmana. Monografia wraz z antologią przekładów, Kraków 2014, p. 17, pp. 79–91.

9 S. Barańczak, “Mały lecz maksymalistyczny manifest translatologiczny,” Teksty Drugie 1990, no. 3, pp. 7–8.

10 A. Moc, Nowe polskie prawo autorskie a kolejne tłumaczenia na naszym rynku wydawniczym, czyli przygody Pinoccia lub Pinokio, [in:] Między oryginałem a przekładem, vol. III: Czy zawód tłumacza jest w pogardzie?, ed. M. Filipowicz-Rudek, J. Konieczna-Twardzikowa, M. Stoch, Kraków 1997, pp. 181–183.

11 J. Zarek, Seria jako zbiór tłumaczeń, [in:] Przekład artystyczny, vol. 2: Zagadnienia serii translatorskich, ed. P. Fast, Katowice 1991, p. 10.

12 P. Kujamäki, “Finnish Comet in German Skies. Translation, Retranslation and Norms,” Target 2002, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 45–70.

13 H. Rappaport, Chekhov in the Theatre: The Role of the Translator in New Versions, [in:] Voices in Translation, ed. G. Anderman, Clevedon – Buffalo – Toronto 2007, pp. 66–77, see esp. pp. 68 and 74.

14 Selected Masterpieces of Polish Poetry, trans. from the Polish by Jarek Zawadzki, [Charleston, S.C.] 2007.

15 A. Legeżyńska, Struktura serii, p. 195. This view is closely repeated by Dorota Urbanek, cf. D. Urbanek, The Translators’ Adventures in “Alice’s Wonderland,” [in:] Translation and Meaning, Part 6, ed. M. Thelen,

B. Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, Lodz – Maastricht 2002, p. 473.

16 Cf. the negative response, both on aesthetic and ethical grounds, to Maria Leśniewska’s experimental “collage” translation of Baudelaire’s poem Podróż (orig. Le Voyage): Z. Bieńkowski, “W sprawie Baudelaire’a,” and

J. Waczków, “Ryzyko,” Literatura na Świecie 1985, no. 3 (164), pp. 354–364.

17 G. Ojcewicz, Granice serii, [in:] G. Ojcewicz, Epitet jako cecha idiolektu pisarza, Katowice 2002, pp. 375–404.

18 Cf. M. Skwara, “Wyobraźnia badacza – od serii przekładowej do serii recepcyjnej,” Poznańskie Studia Polonistyczne. Seria Literacka 2014, no. 23 (43), p. 107.

19 E. Balcerzan, Tajemnica istnienia (sporadycznego) krytyki przekładu, [in:] Krytyka przekładu w systemie wiedzy o literaturze, ed. P. Fast, Katowice 1999, p. 34.

20 Urbanek, The Translators’ Adventures, p. 472.

21 M. Sprusiński, Poeta wielkiego czasu, [in:] T.S. Eliot, Poezje, ed. and afterword M. Sprusiński, Kraków 1978,

p. 229.

22 An early example is a 1991 Polish volume of conference papers (Przekład artystyczny, vol. 2: Zagadnienia serii translatorskich, ed. P. Fast, Katowice 1991). A more specific overview of theory and research up to date is given in Agnieszka Adamowicz-Pośpiech’s book, which also brings analyses of Polish retranslations of several works by Joseph Conrad (A. Adamowicz-Pośpiech, Seria w przekładzie. Polskie warianty prozy Josepha Conrada, Katowice 2013).

23 Skwara, Polskie serie recepcyjne wierszy Walta Whitmana, p. 11.

24 Skwara, Polskie serie recepcyjne, pp. 11, 16.

25 Barańczak, “Mały lecz maksymalistyczny manifest translatologiczny,” p. 36.

26 A. Bednarczyk, W poszukiwaniu dominanty translatorskiej, Warszawa 2008, p. 13; A. Bednarczyk, Wybory translatorskie, Łódź 1999, p. 19.

27 M. Kaźmierczak, “Jak wygląda koniec świata? Dominanty w przekładach wiersza Czesława Miłosza,” Między Oryginałem a Przekładem 2012, vol. 18: Dominanta a przekład, ed. A. Bednarczyk, J. Brzozowski, pp. 97–115.

28 Urbanek, The Translators’ Adventures in “Alice’s Wonderland,” p. 473.

29 L. Hewson, AnApproach to Translation Criticism. Emma and Madame Bovary in Translation, Amsterdam 2011.

30 T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, [in:] T.S. Eliot, Wybór poezji, ed. K. Boczkowski, W. Rulewicz, introd. W. Rulewicz, Wrocław 1990, pp. 3–9. All subsequent citations will be to this edition.

31 Cf. J. Czechowicz, Poezje zebrane, ed. A. Madyda, Toruń 1997, pp. 478–484.

32 T.S. Eliot, Pieśń miłosna J. Alfreda Prufrocka, trans. W. Dulęba, [in:] T.S. Eliot, Wybór poezji, ed. K. Boczkowski, W. Rulewicz, wstęp W. Rulewicz, Wrocław 1990, pp. 9–14. First published in: Znak 1948, no. 7. All subsequent citations will be to the 1990 edition.

33 T.S. Eliot, Poezje wybrane, introd. W. Borowy, Warszawa 1960. For Prufrock see pp. 43–51.

34 T.S. Eliot, Pieśń miłosna J. Alfreda Prufrocka, trans. M. Sprusiński, [in:] T.S. Eliot, Poezje, ed. and afterword M. Sprusiński, Kraków 1978, pp. 7–13. All subsequent citations will be to this edition.

35 There exists a rendition contemporary with Sprusiński’s one, penned by Jerzy Niemojowski and published – together with an essay on both Eliot and the art of translation – in London, in a limited edition (Miłosna Pieśń [sic] J. Alfreda Prufrocka, trans. J. Niemojowski, [in:] T.S. Eliot, Dziewięćpoematów. Przekład i szkic o teorii i praktyce przekładu poetyckiego, Syrinx 1978, no. 1, Sumptibus privatis Londini, pp. 51–54). This was printed explicitly “for restricted distribution” (cf. the note on editorial page) and was not known to wider readership in Poland. Fully conscious of the importance of Skwara’s reservations about the “constructedness” of a translation series, which is primarily in the eye of the researcher, I intend to turn this from a disadvantage to an asset: Niemojowski’s translation will be excluded from the present study on the grounds that in all probability it does not belong to any quality quest as perceived by an interested but non-specialised reader in Polish.

36 T.S. Eliot, Śpiew miłosny J. Alfreda Prufrocka, trans. A. Pomorski, [in:] T.S. Eliot, W moim początku jest mój kres, trans. and ed. A. Pomorski, Warszawa 2007. First published in: Twórczość 1993, no. 1, pp. 3–6. All subsequent citations will be to the 2007 book edition.

37 T.S. Eliot, Pieśń miłosna J. Alfreda Prufrocka, trans. S. Barańczak, [in:] Od Walta Whitmana do Boba Dylana. Antologia poezji amerykańskiej, trans. S. Barańczak, Kraków 1998, pp. 110–115. All subsequent citations will be to this edition.

38 T.S. Eliot, Pieśń miłosna J. Alfreda Prufrocka, trans. K. Boczkowski, [in:] T.S. Eliot, Szepty nieśmiertelności, trans. K. Boczkowski (2001), Toruń 2013, 5th ed., pp. 96–100. All subsequent citations will be to the 2013 edition. The 6th imprint of 2016, called “ultimate” by the translator, was also consulted – it carries minor lexical changes and punctuation retouches (not always fortunate) which do not affect the passages cited in the present article and do not influence assessments made here..

39 M. Perloff, “Awangardowy Eliot,” trans. T. Cieślak-Sokołowski, Czytanie Literatury. Łódzkie Studia Literaturoznawcze 2012, no. 1, p. 284.

40 Perloff, “Awangardowy Eliot,” pp. 284–286.

41 J.F. Hooker, “La Chanson d’amour de J. Alfred Prufrock” (Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, Pierre Leyris, Maurice Le Breton), [in:] J.F. Hooker, T.S. Eliot’s Poems in French Translation: Pierre Leyris and Others, Ann Arbor [in England: Epping] 1983, pp. 45, 57.

42 M. Heydel, Obecność T.S. Eliota w literaturze polskiej, Wrocław: Wyd. U. Wrocławskiego 2002, pp. 154–155.

43 Heydel, Obecność T.S. Eliota w literaturze polskiej, pp. 155–156.

44 J. Ward, “Kilka luźnych uwag na temat najnowszego przekładu poezji Eliota,” Przekładaniec 2008, no. 21, p. 226.

45 U. Eco, Dire quasi la stessa cosa. Esperienze di traduzione, Milano 2004, p. 274. Eco discusses selected points of translating Prufrock into Italian and French on pp. 270–275.

46 Eliot, Szepty nieśmiertelności, translator’s note on p. 102.

47 Cf. Eco, Dire quasi la stessa cosa. Esperienze di traduzione, p. 270.

48 The point emerged in critical discussions in the context of the “masters of Siena” replacing Michelangelo in Pierre Leyris’s French version of Eliot’s poem. Umberto Eco points out that mentioning the Sienese school of painting requires some actual knowledge of art, while a reference to Michelangelo may well remain superficial (Eco, Dire quasi la stessa cosa, p. 271; cf. also Hooker, T.S. Eliot’s Poems in French, p. 52, on the reception of Leyris’s solution).

49 Cf. J.X. Cooper, The Cambridge Introduction to T.S. Eliot, Cambridge 2006, p. 44.

50 Cf. Eliot, “A Commentary,” The Criterion 1933, vol. XII, no. 48, p. 469.

51 Critics disagree as to whether there is a silent companion, a confusion to which the poet himself has added. However, Thomas Kinsella convincingly shows in his close reading that as the monologue progresses, it unfolds that the speaker must be alone (T. Kinsella, Readings in Poetry, Dublin 2006, pp. 40, 48).

52 H. Kenner, Bradley, [in:] T.S. Eliot. A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. H. Kenner, Englewood Cliffs, N.J. 1962, p. 36.

53 Kinsella, Readings in Poetry, p. 40.