1.

One reason for a change in the meaning of a literary term can be the reassessment of whether its current definition corresponds to the reality it refers to. This can be spurred on by new or newly interpreted literary trends, seasonal reconsiderations of artistic devices, the discovery of previously unseen configurations of elements in a work, and so on. We are familiar with these processes from time immemorial; it suffices to mention, for example, such storied keywords of the poetic lexicon as metaphor, mimesis, form, tragedy. The transformations of metaphor as an interpretative category speak volumes. Had the original sense of this term not undergone critical review and transfiguration over many centuries, we would have been condemned to intellectual stagnation where this area, so pivotal to our understanding of art, is concerned.

Analogous discussions arise, sometimes immediately, with regard to new writerly innovations in terminology (Viktor Shklovsky’s ostranienie, or “making strange”; Roman Ingarden’s “places of indefinition,” Mikhail Bakhtin’s “polyphony,” and in the Polish context, Artur Sandauer’s autotematyzm or “self-referentiality”). Autotematyzm can serve here as a most instructive example. I remember how in the 1970s, on the steps inside Staszic Palace in Warsaw, Artur Sandauer loudly inveighed against critics of his concept, his wrath aroused not so much by their polemical interventions as their “corrective” ambitions.

“Tell me, by what right does an Andrzej Werner become the owner of my concept of autotematyzm, rearranging its meanings and vectors?” This angry question was in fact addressed mainly to Janusz Sławiński, but since Sławiński remained impenetrably silent, I, being young, untested, and impetuous, took the liberty of remarking that one argument in favor of Werner’s or other similar practices could be the value of discovering what emerges from the confrontation of a young concept with diverse literary realities…

“What realities?” the author of Bez taryfy ulgowej (Full Price of Admission) replied with indignation, not to say howled. “We are not living in the age of positivistic faith in objective, identically perceived realities!”

At that point, I thought to myself how true it is that we encounter not naked realities but our own interpretations of literary phenomena. But if that is true, the scholar has a choice between either rejecting another scholar’s term and replacing it with his own, or partially remaking the borrowed concept according to his own personal vision of literature. (Autotematyzm has met and will continue to meet with both types of response.) Back then, on the steps of the Staszic Palace, I did not continue with that thread of discussion, understanding, a little too late, that in a clash with Sandauer, the safest option was to maintain, like Sławiński, a philosophical silence.

These days, I feel justified to some extent in defending the principle of the scholar’s right to adapt others’ new terms and reshape their concepts by the fact that my own ideas have been subject to analogous processes. Two in particular, “lyrical strategy” and “transposition series,” have been revised, reinterpreted, expanded, inverted. Some interventions I am eager to dispute, others, quite a good number of them, I accept with humility. What is at stake is not an individual’s attitude, but the semantics of names, which are scholarly tools. Their newness is generally a matter of degree, and this applies to both the signifiant, and the signifié. They are rarely neologisms with no relation whatever to existing, familiar words. Usually the new terms, formed in the scholar’s native language or translated from a foreign tongue, are shaped from elements that have their own previous meanings, grounded either in everyday speech or in specialized codes of the discipline. They ought to be treated with respect. In proposing the category of “lyrical strategy,” I have to take into account the polysemy of both component words, “strategy” and “lyric,” and therefore be ready for someone to raise the issue of the meanings I have put aside; the collective memory of the various uses and contexts of “transposition” and “series,” invited to make the compound “transposition series,” will also inevitably take voice and make itself known.

2.

I was moved to make the preceding remarks by a discussion at the Department of 20th Century Literature, Literary Theory and the Art of Translation at Adam Mickiewicz University in January 2015 on the subject of the theses put forward by Jahan Ramazani in his book A Transnational Poetics (2009), moderated by Tomasz Mizerkiewicz, who had previously supplied us with photocopies of the book’s first chapter (the rest of the book, together with responses to it, is available in the vast morass of the internet). In the discussion, all of the typical features I have sketched of the way we assimilate other scholars’ ideas were enunciated. Diverse reading habits, divergent literary geographies, differences in approaches to poetics have brought about temporal and spatial shifts within phenomena perceived as transnational. What appears in the eyes of the architect of transnational poetics to be something new, driven by globalization and verified by Post-Colonialism, many of us believe to be shared with previous epochs, such as the Renaissance. Furthermore, it was difficult to assent to the claim that the area of poetry is currently going through singularly profound changes, ostensibly until recently a “stubbornly national” art form (in T.S. Eliot’s words, quoted by Ramazani) and “the most provincial of the arts” (Auden, also quoted by Ramazani), and only recently become triumphantly hyper-intercultural; Polish Studies, with its memory of earlier poetic currents, constantly penetrating linguistic, cultural and national boundaries, could not assent to such a one-sided formulation; Ramazani’s choice was not confirmed by observation of prose or dramaturgy, each of which comes in both “stubbornly national,” strongly “provincial,” incarnations and daringly borderless ones. And finally, ever greater political, attitudinal, economic, and commercial obstacles (relating to the distribution of newspapers, magazines, and books) have, in the recent past, paralyzed communication within the sphere of Eastern European literatures (Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Byelorussian, and others), signaling a far less joyous perspective than Ramazani, watching the world from a different vantage point, would like to believe. All of the above, and several more, exaggerations of the initial watchword called for its reinterpretation. Works by Jan Kochanowski, Cyprian Norwid, Joseph Brodsky, Teodor Parnicki, and Tadeusz Różewicz, invoked in the discussion together with their authors’ biographies, turned out to amount to something more than simply interchangeable examples of norms, neutral in relation to their model: they had in fact influenced the configuration of those norms. Incidentally, Ramazani’s “transnational poetics” also has its antecedents, though none is identical with his project: reviewers of his book have called our attention to the writings of the American pragmatist Randolph Silliman Bourne, who in 1916, well in advance of the globalization we know today, wrote about a “Trans-National America.”

3.

In Polish, the phrase “transnational poetics” automatically finds itself (in view of its morphology) among a special group of concepts belonging to literary scholarship: these concepts are two-layered; in them, the lower level of meaning is unavoidably complicated by the higher level. An analogous word-formation (and, simultaneously, semasiological, or meaning-creation) mechanism has generated numerous terms used in the humanities lexicon, often through the aid of the prefixes “trans,” “neo,” “anti,” “extra,” “para,” “quasi,” “re,” and “post.” When using products of this type, we should not pass over their etymological roots in silence. We cannot glean the meaning of the word “neo-Romantic” without some consideration of what is meant by Romanticism tout court. Likewise, we quickly get lost in the labyrinth if we attempt to grasp “anti-traditionalism” without a prior definition of “traditionalism.” A similar succession of diagnoses is required in defining “judgment,” “literature”, “structuralism,” and other words, conditioning our grasp of the (incomparably trickier and more nebulous) meanings of “quasi-judgment,” “paraliterature,” and “post-structuralism.”

It follows from the above reflections that we should begin our analysis of “transnational poetics” with a clarification of what a “national poetics” means. If we managed to do that, we could attain– at a lower level of abstraction, closer to the very life of literature– the means to master the mechanisms that govern particular systems we would distinguish as Polish poetics, French poetics, Russian poetics, Portuguese poetics, and so on. It is only between or among systems thus designated that we can observe transfers, translocations, transfigurations of literary structures or fragments, perceiving the mechanisms and results of these displacements as the subject of transnational poetics studies. The trouble is that such an entity is difficult to describe. While many of us have no problem employing the concept of “national literature” or the “history of national literature,” one would search in vain for its apparent twin concept, “Polish poetics,” in the lexicons of Polish studies. There is, however, a whole range of related designations that refer to selected segments or aspects of poetics: versification, stylistics, genres. I have in mind Maria Dłuska’s study Próba teorii wiersza polskiego (An Attempt at a Theory of Polish Poetry), Adam Ważyk’s Adam Mickiewicz a wersyfikacja narodowa (Adam Mickiewicz and National Versification). Linguistics scholars are untroubled by any doubts as to the existence of not only “stylistics of Polish language” (Teresa Skubalanka), but even the wider field of “Polish stylistics” (Halina Kurkowska, Stanisław Skorupka). There is further “Polish linguistic genre theory” and, of particular and pressing importance for our purposes, “Polish literary genre theory,” on the title pages of an anthology edited by Romuald Cudak and Danuta Ostaszewska. Is it an accident that the “national” character of certain formidable sectors of poetics remains unquestioned, while at the same time poetics as a whole somehow eludes national quantifiers?

Let us observe, however, that in the examples mentioned above, the words “versification,” “stylistics,” and “genre theory” do not refer to the same kind of reality. They indicate intersecting, but far from identical orders dominating speech, literature, or literary studies. Some of them exhibit the internal features of (Polish) verbal art, others describe research projects of (Polish) literature scholars whose theories of versification or genre theory need not draw inspiration exclusively from domestic literary sources. So what, if we could call it into existence, would a “national poetics” entail, since its component parts, both “poetics” and whatever is “national,” are conspicuously marked by a dizzying ambiguity?

It is at once clear that various iterations or states of this internally complex field will operate in our discussion. We will define poetics thus:

(1) the aggregation of tools used for distinguishing and delimiting recurring models of literary structures, components of works, or relationships occurring between or among individual components (literary terms plus their definitions);

(2) systems of organization of the utterance active in aggregates of literary works;

(3) the artistic organization of a particular individual work.

Like “poetics,” the definition of that which is “national” is impossible to capture in a homogeneous paradigm. We become aware of the national character of literary phenomena, meaning their belonging to one national literature or other, through connecting together the following: (a) ethnicity, (b) culture, and (c) language. The categories mentioned are neither strictly separable or alternate, nor eternally bound together and mutually complementary. They are capable of falling into the one category as well as the other.

As should be clear, within the range of problems (and enigmas) delineated here, a uniform definition of poetics, encompassing all of its manifestations as well as its national or inter/supra/transnational characteristics, is hard to come by. The matter is in need of some sorting out. And because this “matter” is twofold, we must answer the question as to which territory here has primary, and which secondary jurisdiction. One can imagine an attempt at a genre study of the existing conditions of national literary cultures – considering the changing methods used in each for managing poetic resources. And it is tempting to consider a genre study of developments in poetics reflecting the experiences of national cultures and languages. In view of my goal being set within literary scholarship, I choose poetics, naturally enough, as the main object of my observations to follow.

4.

Poetics, understood as a lexicon of defined terms describing literary compositions, their component parts or relationships among elements in a work, is neither wholly transnational, nor composed exclusively of national repertoires. It contains concepts known and tested with reference to all literatures, but also designations specific to local literary facts. Its elements (in the most basic, schematic sense) can be presented on a bipolar scale, between a group of concepts with universal scope and application and groups of terms that are local in origin and applicability.

Within the range of universal terminology we find only certain categories from the area of poetics that have attained the status of basic coordinates of literature and model norms of literariness.

This statement leads to the fundamental question, who or what caused the choice of those categories, and in particular, whether the decisive criteria were qualitative, objective, essential, and impartial, or functional, pragmatic, and subjective. New doctrines of scholarship demand an unambiguous stance in the dispute between pragmatists and essentialists. In my opinion, literary phenomena are faced – in various circumstances and to differing degrees – with pressure both from the partisans of “essence” and the dictates of “existence,” to use the dichotomy of Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous aphorism. In the group of universal terms of descriptive poetics, this duality becomes potently clear. The fact that writers and scholars from near and distant times and places are able to understand each other’s understanding of concepts as central to the writer’s art as poetry, prose, poem, description, novel, narrator, lyrical persona, character, plot, narrative, style, and motif, constitutes an indirect, but significant proof of the existence of literature as one of the sovereign forms of interpersonal communication. From this perspective, we can speak of the non-arbitrary, qualitative nature of the group of universal terms. But because the notion of literature and the registers of its coordinates are subject to endless verifications, dependent in turn upon evolving methodologies, it is crucial to consider not only the qualitative but also the functional status of these terms.

From the historical point of view, universal poetics comes later than the various local versions. All of its lexicons have a local origin (beginning with the word “poetics,” which was conceived in Greek antiquity), and all had to belong to local literary cultures as generalizations derived from the experiences of writers, readers and scholars; if it happened that the same features found themselves named and described in the lexicons of numerous temporal and spatial literary contexts simultaneously, like partial doppelgangers, still, none of these contexts was in any way deprived of its national peculiarities. Now these same concepts, perceived as universal, have either completely lost the memory of their own (linguistically hybrid designations aside) local beginnings, or that memory is, even to those who possess it, irrelevant and put to no scholarly use. Regarding this group of terms, we might say what Ferdinand de Saussure said about the system of language: that in the synchrony of speech, as in a game of chess, what matters is our current position, not the moves that put us there.

In the aggregations of terms with local origins, the link between names for particular literary structures or devices and the national cultural context remains known and active. For Polish writers and scholars of Polish literature, the following terms preserve the memory of the historical circumstances of their formation (and, often, the name of the creator of the concept or the inventor of the artistic form it describes): fraszka (a specific kind of epigram), gawęda szlachecka (a tale of the aristocracy), heksametr polski (Polish hexameter), Tadeusz Peiper’s zdanie rozkwitające (expanding sentence, related to Peiper’s układ rozkwitania or system of expansion), Julian Przybos’s międzysłowie (inter-words), Janusz Sławiński’s wiersz różewiczowski (Różewiczean verse) and poezja lingwistyczna (linguistic poetry), and Wisława Szymborska’s moskalik (an epigrammatic 4-line poem derived from a quatrain in Rajnold Suchodolski’s 1831 poem Polonez Kościuszki). Undoubtedly certain among these names are nothing more than local variants of universal models: the fraszka is a version of the classical epigram, Polish hexameter is an adaptation of previous hexametric norms, Różewiczean verse has been proclaimed a Polish variation on free verse. Other concepts, such as gawęda szlachecka, nicely illustrate Lucien Goldman’s theory of the homology of structures between genres and national customs. The newer of these terms (system of expansion, inter-words, linguistic poetry) are attempts to define devices that, in the Polish literary context, were discovered relatively recently.

In addition to universal (transnational) and local (national) terms, lexical elements from the poetics arsenal of local, but foreign, cultures also function in the glossaries of literary scholars who employ the language of poetics. These, too, have wide-ranging sources: from folklore (Ukrainian dumka, Russian chastushka) to fragments of historical poetics that demand recognition of their rights, sometimes after a period of dormancy (Provençal alba, serena, stanza; Russian dol’nik and syuzhet, German bildungsroman, English Sternean narration). These can be, like the Polish gawęda, inscriptions of the national culture’s particular customs into a previously existing convention (as is also the case with Russian skaz). The richest group of concepts, it appears, are the names of artistic innovations that preserve the living memory of their conception: Breton’s écriture automatique, Marinetti’s parole in libertà, the Russian Futurists’ zaum, the nouveau roman developed by French mid- twentieth century novelists, primarily Robbe-Grillet.

Where does such terminology, “cognizant” of its national provenance, belong on the scale between the poles of locality and universality? Its place is mobile, dependent both on the degree to which a given term has been disseminated, and its applications, as well as on whether the term continues to refer exclusively to writing practices of one literary sphere or is exemplified in an expanding range of languages and cultures of world literature. All different kinds of relations enter into the picture: bilateral, trilateral, and more. An example of this could be the term вирши, which functioned in Russian discourse on versification at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, at first signifying tonic verse (a concept imported from Ukrainian poetry), and later, a system of syllabic verse based on Polish poetry.

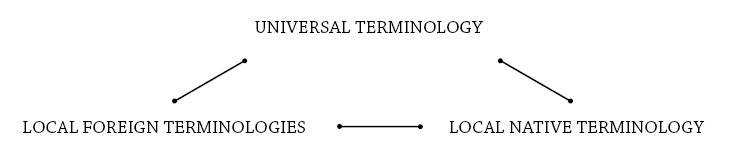

Our diagram thus needs to be diversified and made triangular:

It is quite easy to perceive that local concepts from descriptive poetics (both native and foreign) can tend toward either the category of local terminology or that of universal. But is it possible, as the diagram suggests, for concepts from universal terminology to become displaced into individual local terminologies? The answer to that depends on how we describe the items that are displaced. In lexicographical and didactic practice, concepts from poetics function as conjunctions of three elements: names, definitions, and exemplification. The three are not equally crucial in shaping the identity of the term. A change of name, when the definition and the nature of the examples remain the same, is merely a superficial innovation. The different names for the same phenomena in various languages have no effect on their meaning and function. A change in the exemplification may be important if the new examples reveal properties of the device that were absent in previous examples. The reconstruction of a term’s definition has the most far-reaching results; especially because in literary studies, and therefore in poetics, a definition is a ready synecdoche for a theory, a condensed representation of a whole broader concept. If within a local school of literary studies the theory of some concept considered universal (for example metaphors) undergoes a fundamental revision (as has occurred in the work of Polish theorists Jerzy Pelc and Anna Wierzbicka), but the new view obtains immediate recognition only among the ranks of the theorist’s compatriots, the concept is, for a time, “withdrawn” from transnational universal terminology and reattached to a local, national branch of terminology.

5.

The above observations, based on an overview of the terminological repertoires of descriptive poetics, are in some ways similar and in other ways markedly different from the conclusions that may be drawn from a survey of historical poetics, whether in its collective or individual manifestations.

The most consequential differences relate to the internal configurations of both kinds of poetics, and therefore the boundaries and scope of their activities. As I mentioned earlier, the basic determinant and final goal of any term in descriptive poetics consists of its definition, treated as pars pro toto of the theory of a literary phenomenon, while examples and the name serve the verification of the definition or theory. Here immanent poetics can save or degrade, modify or amplify the explanations of a formulated poetics’ keywords.

In recognizing and distinguishing the forms of artistic organization of particular aggregations of works, we come into contact with other kinds of interdependence among them. A basic goal of scholarly endeavor becomes the maximally precise interpretation of the norms functioning within a given aggregate. If this aggregate has its own formulated poetics (whether in the artists’ declared program or in the scholar’s diagnosis), then those guidelines become instrumental and helpful, while particular categories may be selected or rejected according to how useful they prove in the reconstruction of internal artistic structures.

As a result, the semantic dimensions and functions of the names and definitions of these structures change. I have in mind such names – also titles of scholarly works – as Dmitrii Likhachev’s Poetics of Old Russian Literature, Michał Głowiński’s Poetyka Tuwima a polska tradycja literacka (Tuwim’s Poetics and Polish Literary Tradition), Bożena Tokarz’s Poetyka Nowej Fali (Poetics of the New Wave). Each of these titles functions as a signature code for a certain group of works, indicates the group’s place in the agglomeration of literary texts, signals its position. The definitions of such disparate “poetics” are located in the sphere of theory, but above all they mark paths of interpretation of particular works and relationships among them. In the course of an interpretation, a chosen aggregate of texts can be treated as a complicated, but to some extent coherent, literary composition, what I have in the past proposed we call a multitext transmission. The third component indispensable to the terminology structures of descriptive poetics, exemplification, here turns out to be either deceptive or in need of profound regeneration, for in fact a given group of texts does not exemplify devices external to itself, does not illustrate a separate, disposable poetics, but constitutes and simultaneously consummates a particular version of an immanent poetics.

The number of possible literary aggregates, and hence criteria for their differentiation and demarcation, would seem to be uncountable, and certainly unpredictable. Is each aggregate, sometimes called a “greater whole,” capable of constituting the system of norms of its own poetics? Without a doubt the answer is no. Works by women authors, juvenilia, interwar publications, seasonal new releases, magazine poems, each of these and similar constellations can be set aside from the deluge of texts, and in each an internal artistic coherence can be intuited, yet the search for that coherence often ends in failure. Frequently disputes on the existence of shared poetics in particular aggregates remains undecided. This is especially true with regard to the inheritance of a literary period or epoch. The older the period, the less literary evidence available, the greater the likelihood of a common poetics for all its surviving works. This is the direction Likhachev was heading in with his work on the poetics of Old Russian literature. Let us observe that to recognize the literature written in one historical space as susceptible to definition within the rubric of a poetics demands the unification of all its artistic currents. Even in Old Polish times diverse forms of verbal art coexisted (Polish and Latin, secular and religious, court and folk); to attempt to capture that varied group under a common appellation would be a highly controversial decision. The closer one comes to modernity, the more difficult such unification of literary norms becomes. Even more questionable are attempts to standardize literary norms by generalizing from works written in the most recent, modern and postmodern, eras or systems.

As with lexically-based poetics, so in poetics oriented toward literary aggregates neither national nor transnational fields are dominant. Here we deal, on the one hand, with aggregates whose internal poetics are monolingual, monocultural, monoethnic, and thus national (in addition to Likhachev, Głowiński, and Tokarz, other examples we might mention would include Zofia Szmydtowa’s Poetyka gawędy (Poetics of the Tale) and Mikhail Bakhtin’s Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, among many others). On the other hand, there are also genre-based poetics, functioning in a multiplicity of national milieux: Eugeniusz Kucharski’s Poetyka noweli (Poetics of the Novella), Joanna Dębińska-Pawelec’s Vilanella. Od Anonima do Barańczaka (The Villanelle. From Anonymous to Barańczak); let us consider the title of that work’s first part, “Poetyka i dzieje gatunku” (Poetics and the History of the Genre), and its introduction, “Wprowadzenie do poetyki gatunku” (Introduction to the Poetics of Genre). We might further add the immanent poetics of artistic movements such as Romanticism, Expressionism, Futurism, and Surrealism, which cut across numerous cultures and languages. And, finally, we should not neglect the work of such bilingual authors as Stanisław Przybyszewski, Bruno Jasieński, Thomas Themerson, or Gennadiy Aygi. In this area transnationality appears to be a useful and incisive concept, as is the nationality of the various individual internal poetics of literary aggregates.

6.

Like the poetics of the aggregate the poetics of the individual literary work, too, is the result of an interpretation. To interrogate a work’s “nationality” means to interrogate the presence in it of content relating to national consciousness and memory, variously valorized along a spectrum from ecstasy to disinheritance. This content manifests itself together with the material covered in a given work (ways of managing this material constitute the poetics of a work). When I refer to literature’s material, I have in mind all of its values or content – everything transferred to the work by means of linguistic combinations. What we are dealing with is thus, naturally, not the contents of national consciousness and memory, but also what is philosophical, scholarly, imaginative, literary (stored in tradition), and so on. The fact that the above distinctions lack the desired “punch,” and their immaculately “pure” hypostases are thinkable only in theory, does not mean we should renounce their use. The prose categories of socially engaged, psychological, political, or fantasy, and the lyrical categories of religious, metaphysical, patriotic, political, self-referential, pastiche (intertextual) evoke manifold doubts – considering their mutual permeation in literature (and in the human mind), and in general, aside from that, imperfect labelling makes it (even) more complicated getting around the landscapes of literature.

What is the place in the dense thicket of literary forms for national content or values? They can appear in each of the varieties of narrative or poetic literature indicated above (as well as dramatic and nonfiction forms). In view of the internal diversity of the category at hand, it is incredibly difficult to point to a work – socially engaged, self-referential, psychological – in which we don’t find at least a trace of “that, which is national.” It might be said, to quote Zbigniew Herbert’s Rozważania o problemie narodu (Reflections on the Problem of the Nation), that in general, this is the last knot “to be broken free of by the prisoner.” On the other hand, however, the neutralization, reduction or deconstruction of national values often becomes one of the goals sought after by the poetics of a work. What is national is opposed to what is human and universal, though not necessarily transnational.

The first part of this article discussed how the “nationality” of a literary work or group of works manifests itself in a variety of ways, in three not entirely identical and not entirely different contexts: linguistic, cultural, and ethnic. These contexts not only interpenetrate each other, but also enter into conflict with one another. They support or supplant each other. Tensions within what belongs to the national become noticeably activated within the structure of a work perceived through its numerous “layers.”

A few examples. A sophisticated, bravura manipulation of Polish language, skirting the borderline of untranslatability, can serve to express a universal cosmological vision of the world, freed from all national characteristics (Bolesław Leśmian’s Eliasz). A caricature, all but grotesque, at the level of representation, of cultural symbols of Polishness, can coexist with an apotheosis of the artistic possibilities of Polish at the linguistic level (Witold Gombrowicz’s Trans-Atlantyk). A declared flight from Polishness (“Must I still be a Pole?”) can be accompanied by “transparent” language, constituting an attempt to create an illusion of universal speech, unmarked by any nationality (Miron Białoszewski’s Klapa). The typology of the totality of such combinations is a task for the poetics of the future. May it come swiftly!

The poetics of works that exceed the limits of monolingualism and national monoculturalism, especially works that represent ethnic conflicts or alliances, differ from the conditions sketched above in their degree of complexity. The category of “transnationality” seems pertinent and useful with regard to certain texts, but insufficient in relation to others. Transnationality comes into its own where the literary protagonist in an ethnically diverse world shifts between languages and cultures. Examples could be Białoszewski’s Wycieczka do Egiptu (Trip to Egypt), Obmapywanie Europy (The Mapping of Europe), and AAAmeryka (AAAmerica). With regard to literary images of national slaughters, ethnic cleansing, pogroms, extermination, border struggles, and so on, the prefix “trans” fails to convey the intensity and stakes of the drama.

7.

Time for conclusions. The idea of a transnational poetics can be a positive impulse, awakening the imagination of scholars toward organizing the tools of their inquiries and the artistic devices of literary creation according to criteria that correspond to the actually existing state of literature in its many important sectors and phases. We must nonetheless anticipate the existence of works whose relationship to the categories of nationality and transnationality will be indirect, problematic, fluid, or neutral. The crucial problem is that both nationality and its emergent transnational superstructure are specific ways of branding descriptive poetics, the poetics of literary aggregates and the poetics of the single work. Like all such forms of branding, they are labile, situational, and gradual, to the point of oblivion or self-contradiction.

***

The theses and propositions presented in this article demand more extensive literary evidence and more detailed empirical justification. Due to lack of space, I will take the liberty of referring readers to some earlier works of mine in which these problems have been tackled with more precision. Styl i poetyka twórczości dwujęzycznej Brunona Jasieńskiego. Z zagadnień teorii przekładu (The Style and Poetics of the Bilingual Work of Brunon Jasieński. Problems of Translation Theory), Wrocław 1968. “Ekspresjonizm jako poetyka” (Expressionism as Poetics), in: Kręgi wtajemniczenia. Czytelnik, badacz, tłumacz, pisarz (Circles of Initiation. Reader, Scholar, Translator, Writer), Kraków 1982. “Polska Mirona Białoszewskiego” (Miron Białoszewski’s Poland), in: Śmiech pokoleń – płacz pokoleń (Laughter of Generations – Lamentation of Generations), Kraków 1997. See also “Ojczyzna wobec obczyzny” (Homeland and Strange land) in the same volume. “Jednojęzyczność, dwujęzyczność, wielojęzyczność literackich ‘światów’” (Monolingualism, Bilingualism, and Multilingualism of Literary “Worlds”), in: Tłumaczenie jako „wojna światów”. W kręgu translatologii i komparatystyki (Translation as “War of the Worlds.” In the Sphere of Translation and Comparative Studies), Poznań 2011. See also “Pola-sobowtóry. Rewolucja i komparatystyka” (Shadow-Fields. Revolution and Comparative Studies) in the same volume.

translated by Timothy Williams

Przejdź do polskiej wersji artykułu

A b s t r a c t :

Poetics understood as a lexicon of terms defined and illustrated by selected examples, describing literary compositions, their components, or relations between elements in a work, consists of concepts universal or local in scope; the local can be native or foreign. Perception of the genesis of terms changes during the course of literary history. “Nationality” or “transnationality,” formulated as a feature of the poetics of a work or aggregate of works, has a similarly dynamic nature, manifesting in three systems which are neither fully identical nor completely distinct: linguistic, cultural, and ethnic. These systems are not only mutually interpenetrating; they also support each other and conflict with each other.