Anna Gawarecka

a b s t r a c t

“Sir, if you will, everything but

the criminal case is a puzzle;

the case becomes a fragment

carefully extracted from reality,

just a snippet of it, momentarily

caught in the spotlight.”[1]

The structural parameters for crime literature have been the subject of numerous overviews, critical essays, and recapitulations. Yet rarely do these comments exceed the level of superficial claims that firmly classify sensational prose within the scope of mass literature and merely rehash the same statements on its schematic nature and predilection for redundant and predictable endings. On the other hand, in a radical gesture, Roger Caillois dismissed this kind of prose as a strictly intellectual “jigsaw puzzle” that falls outside the parameters of even the most expansive definition of the literary.[2] Mirroring the conclusion Karel Čapek reaches in the 1920s[3] (to name an author unfairly neglected by Polish criticism), Caillois uses this ostracizing maneuver firstly to present a paradigmatic “invariant” of the genre, cleansed of all external traces that might interfere with the “cryptographic” dimension of plot construction, and consequently, to demonstrate that crime literature, having attained its own particular state of emotional barrenness, has once again converged with the “conventional novel that is rambling and expansive, where there is neither a chronological inversion, nor a logical chain of cause-and-effect, nor a reconstruction of an event that has already come to pass. The narration has so much in common with the crime novel that it must certainly be its progeny – through the emphasis of the detective novel’s sensational attributes and the roles played by bandits and detectives, and the space occupied by death and premeditated murder. What had once been a pretext and point of reference has now become an issue of utmost importance. Agitation trumps reflection. The image of violence takes precedence over the difficulty of disjointed reasoning.”[4] In other words, Caillois proves that crime prose has traced an evolutionary circle that is nearly complete. By reactivating elements that fell by the wayside due to the abstraction of genre attributes, the prose has regained (at least potentially) the right to its place within the world of a “high brow“ literary value system. After being held in suspicion for so long (pun intended) and treated dismissively, murder, which has always been the most disturbing and unconditionally condemned signifier of transgression in interpersonal relationships, has ascended to the rank of a “great cultural theme.“ The renaissance unfolding today. which has been noted so assiduously among scholars, inhabits a new cultural atmosphere. Literature that relies on simply duplicating original genealogical laws will no longer go unpunished, for it will necessarily be exposed to allegations of being outmoded and clinging to a naive faith in the undying appeal of formulaic narrative strategies. For the postmodernist embrace of “experimenting with pulp,” which involves keeping defining genre markers in scare quotes and bracketing all gravitas, plausibility, and mimetic illusions of the structural templates in parentheses, allows us to elevate investigative crime stories to a “higher level of mediation,” thereby exposing the artificiality and contrived nature of the presented world. Yet at the same time, the conspicuous overrepresentation of these stories on the publishing market might prompt us to follow Anna Gembra and ask, “what, if not the exposure of crime and the crime mystery, is the central objective shared by authors of contemporary sensational crime novels? To what ends to they apply the conventions and structure of the crime novel?”[5] In both cases, to examine the causes and effects of this “surplus,” we must also account for derivative activations of the motifs comprising the crime novel’s standard thematic inventory. It is also crucial to identify the various prose strategies that have prompted this resuscitation of calcified schemas and endowed these schemas with surprising semantic values.[6] As a result, experimenting with conventions turns into a kind of polemic on the reader’s “horizon of expectations.” And popular entertainment (rather than disinterested carnivalesque stunts) gains the power to stimulate ethical, social or cultural reflection.

In The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco chose to revive the most “canonical” structural template of the detective novel (in the vein of Arthur Conan Doyle) and justified this decision by asserting the genre’s epistemological potential. At the same time, he enriched the genre’s repertoire of structural elements with more Gothic-in-origin horror tropes and a sense of the uncanny and macabre (among other elements) in order to interrogate the universal relevance of medieval theological disputes today. Since this book’s publication, world literature has witnessed a rise in texts that mobilize popular schemas of the thriller and “enhance” them by setting the plots in various “niche” and/or exotic milieus. In Eco’s later work and the work of other authors, the hierarchy of importance of certain layers of the text change. Pure “entertainment value” is now prioritized over cognitive ambitions and the attempt to diagnose the deficiencies of contemporary social and political life. One thing, however, remains constant, and that is the readers’ fascination with artistic (literary, theatrical, cinematic, multimedia) strategies for explicating mysteries and solving puzzles. As Umberto Eco has argued, “I believe people like thrillers not because there are corpses or because there is a final celebratory triumph of order (intellectual, social, legal, and moral) over the disorder of evil. The fact is that the crime novel represents a kind of conjecture, pure and simple. (…) After all, the fundamental question of philosophy (like that of psychoanalysis) is the same as the question of the detective novel: who is guilty? To know this (to think you know this), you have to conjecture that all the events have a logic, the logic that the guilty party ahs imposed on them. (…) At this point it is clear why my basic story (whodunit?) ramifies into so many other stories, all stories of other conjectures, all linked with the structure of conjecture as such.”[7]

As we know, The Name of the Rose persuasively interrogates the notion that the perpetrator of a series of crimes consciously (and with premeditation) governs the logic of facts. As the parameters of the genre require, the text sets up an “iron-cast” causality of events that ultimately proves deceiving. The impetus to revive the fossilized conventions of the genre, originally seeded by the work of Friedrich Dürrenmatt, involves calling into question the cognitive illusions on which the genre is based and subverting blind faith in the “benevolent power” of deduction. This mode of revival is not, however, the sole possible method for bringing this material back to life. One discrete albeit often epistemologically complimentary way to expand the toolkit of the crime novel’s genre attributes (and one that has been eagerly mobilized by Eco) consists of sampling from the conventions of gothic literature and mystery novels, thus enriching the genre’s creative strategies with plot conventions and compositional devices native to the thriller.[8] Not so long ago, scholars had a tendency to treat thrillers as purely commercial products “bereft of literary value” (to quote Teresa Cieślikowska, who is referencing Boileau-Narcejac[9]). More recently, however, scholars seem to look upon the genre with growing generosity, for within this material, they have discovered a “blurring” of genres (to use Clifford Geertz’s term).[10] They have also identified this genre as one that aligns, to a certain extent, with socially critical, political, and ecological genres. As a result, they feel justified in taking seriously the prerogative diagnoses of the books.[11] This dependent relationship runs both ways: scholars who address such issues do not rehabilitate the “gory trash” that preys on readers’ “most lowly instincts” so much as they respond to transformations unfolding in the genre and to the indisputable fact that today, we find the signature devices of suspense in the work of writers more obviously classified on a “higher plane” of literary messaging.

Czech literature includes a group of prose writers who are broadly read as the heirs of Eco’s variant of the thriller-as-template. This group includes Miloš Urban and Roman Ludva, although the latter falls in this category less consistently.[12] Both figures belong to a circle of writers who, after debuting in the mid-1990s, have now turned their attention to metahistorical fiction, yet they have done so by way of their own nuanced approaches that involve seeking the material traces of the past that exert concrete and powerful effects on contemporary reality. As a result, their interests tend to prioritize architecture and works of art, and they base their sensational plots on texts on alternative (esoteric) methods for interpreting the meaning of these works (a meaning that is, of course, beyond the layman’s reach). On an intertextual level (and here we should not forget the phantasmagoria of Dan Brown), writers therefore direct their gaze toward capturing a vivisection of so-called conspiracy theory postulates such as those laid out in Foucault’s Pendulum, rather than toward the teleological meditation we find in The Name of the Rose, whose authenticity is confirmed by the author’s scholarly authority on medieval themes.

In Czech literature, however, there is a discrete and entirely indigenous (if I might risk so bold a claim) tradition of combining sensational motifs with the interpretation of the hidden meanings of artistic artifacts. In 1873, Jakub Abres (1840-1914), a neoromantic public intellectual and prose writer, published the story Svatý Xaverius (“Saint Xavier”) in the magazine “Lumír.” At the suggestion of the publication’s managing editor Jan Neruda, who was disturbed by the work’s title and its hagiographic connotations, the story given the genre designation “romanetto.” Thanks to the book’s bestseller status and sweeping popularity, the text became a template on which a new genre form emerged. On the other hand, we might just as well view it as a paradigmatic approach (on Czech soil) to situate the narrative structure of a criminal investigation in the art world. The story’s title references a painting by the Baroque artist František Xaver Palko (1724-1767 or 1770) located in the St. Nicholas Church in Prague. The painting depicts the martyr’s death of Saint Francis Xavier, although the story itself concerns attempts to discover the painting’s “actual” meaning. These attempts are motivated by an erroneous or perhaps distorted interpretation of the painter’s spiritual testament:

“The painting of Saint Xavier as he dies was not rendered only for the eye and for the sake of ennobling the minds of pious Christians. There is more to it than we might find in the works of old masters. There is something in there that would drive thousands to flinch in contempt, but might nonetheless prove beatific for millions… Who, even after standing guard over the painting for years, might be able to concentrate all their thoughts on the image in order to explicate its mystery? Whoever explains this mystery will be of immense value to humanity, for he will possess a spirit of such strength and experience as are necessary to commit deeds of great benefit for all of humanity. Only one thing is needed here: perseverance, and an iron will. Whoever arms himself with such things in confronting this painting will feel a yearning to unravel the mystery of the painting to which Saint Xavier bestowed his treasure of infinite value.”[13]

After being indoctrinated into the positivist cult of a scientific experiment, the romanetto’s hero remains fixated on the message’s literal meaning and therefore manages to completely miss its universal and ethical dimension. Using geometric tools and making complex mathematical calculations based on the painting’s composition, he attempts to reconstruct the locations of what he has literally interpreted as a “treasure of infinite value.” For in the protagonist’s approach, the composition figures as a camouflaged stand-in for an eighteenth-century topographical map of Prague and environs. This interest in the numerical values encrypted in the painting allows him to fully succumb to his obsession, which inevitably has disastrous ramifications for his life plans. The (metaphorical) narrative marker of this is the protagonist’s ultimate death in a Viennese prison. On a visual level, this death suggests a certain resemblance to the suffering of the Jesuit martyr.[14]

František Xaver Palko The Death of Francis Xavier

Scholars seem to agree on the point that the model for Arbes’ narrative structure grew out of his in-depth examination of the theories and creative tactics of Edgar Allan Poe. As it turns out, for Arbes, the self-reflexive comments we find in Poe’s Philosophy of Composition proved to be “a great model throughout his whole life that continued to impress him with its originality and unusual knack for evoking fear in the reader via cold logical construction.”[15] In fact, it is precisely this “ironclad” structural logic that served Arbes in his quest for rational proof. To put it differently, his attempt to encounter everything through intellectual cognition and his refusal to cede any “territory” to the “unsolvable” allow us to situate the romanetto within the tradition of Czech crime literature.

At the romanetto’s origins lies the story of an investigation of the mystery concealed within the subject or diegetic structure of a work of art. To take things further, the painting is endowed with sacred values, and is integrally embedded in sacral space. Its original semantic potential therefore consists of theological and/or confessional meaning in the foreground, while all other values (including aesthetic ones) recede to the background and attain (in the best case scenario) the status of a supportive tool in the work of penetrating the painting’s meaning according to its author’s original intentions.[16] Inverting the hierarchy of values and conceding the status of semantic dominance to other structural elements performs a certain “intensification” of the painting’s textual nature and therefore calls for a different reading strategy that would respect the potential (often making claims, as in Arbes’ case, on the basis of a kind of interpretive usurpation) for alternative readings of the painting’s representation of the world:

“I would say that for the first time, I noticed what was really so remarkable (if not unique) in this canvas. It has nothing to do with painterly technique. It’s all a matter of subject: the reading monk. I mean, all you have to do is look at the title! The monk who reads is the one who will uncover the mystery of the painting! In other words, for the painter, it is enough to have a few indicators of how to create a canvas so that it will persevere through time and coast through the centuries to then become (as only some painters desire, while still others do in quiet suffering) a work of art. But the monk in the painting does not paint – he reads! Later on, in the lower right corner, we find a formula intended to aid painters. (…) At this point, I find that the meaning behind the Tuscan legend expands to great extremes: the painting’s mystery cannot be solved through painting or by scrutinizing the image from up close. It can only be solved in reading. And that’s not all. Perhaps reading is only a metaphor. The endlessness of the chess board that was suddenly spread out before me was fascinating.“[17]

Roman Ludva’s novel Stěna srdce (The Heart’s Wall; 2001) partially replicates the narrative structure of the romanetto by using the device of a compositional frame, the intensification of narrative layers, and the technique of nesting the characters’ statements in “multi-tiered” quotations.[18] The unifying force threading through the book’s many plotlines is the motif of a painting that, according to the medieval Tuscan legend, is encoded with a hidden message from the artist. Allegedly, this inscription bears a “doctrine” for immortalizing the lifespan of the work of art in the moment of (exegetic) reception. It is no easy task to read the text as a “wholesome” crime novel, for it lacks the majority of the enre’s requisite markers (not least the crime motif), but a “guesswork structure,” which, in Umberto Eco’s opinion, underlies the genre’s eternal popularity, commandeers the sequence of events, while references to Raymond Chandler sprinkled throughout the narrative space continue the work of directing the reading process.[19] The mystery’s actual resolution turns out to be shockingly banal. The creative formula encrypted in the painting, meant to endow works of art with a relevance impervious to the passage of time, consists of five Latin words: “PROBITAS, INGENIUM, ASSIDUITAS, GAUDIUM, EVENTUSQUE. MORS –“ (Honesty, talent, hard work, joy and success. Death –”), evoking a cosmic whole of basic ethical values and rudimentary anthropological categories. What’s more, the mystery noted by critics of the work can therefore never be explicated in full. On the other hand, it successfully fulfills its basic narrative function, which is to direct the novel’s protagonist (the Czech painter Josef Hala) who in his youth paid homage to abstract artistic paradigms, towards the “true” artistic road.

This protagonist, who has various sources of protection at his disposal, therefore falls victim to manipulation, for all “good Samaritans” try to stuff him into a pre-programmed framework or identity template and assign him the fixed role of the artist who, while striving toward commercial success, simultaneously works to rehabilitate realist painting that has been cast aside (irrevocably, it would seem) with the rise of avant-garde experimentation. The story of the Tuscan legend has the function of a catalyst of sorts that gives rise to the awareness that art should respond to its viewers’ spiritual and aesthetic needs. In this case, this means that art should respect the principles of figurative aesthetics. To realize this goal, tradition and modernity must harmoniously intersect, and in concrete terms: Gothic painting techniques should be renewed.

The characters in the story Falzum (“Counterfeit”) reach the same conclusions, although this time they are dealing with the conventions of fifteenth-century Flemish painting. The story was published in 2012 within a volume of “classic” crime narratives with this same title:

“In the worst case scenario (…), a few people will write that the contemporary figurative wall painting created by way of traditional techniques does have a future. In the best case scenario, the European elite of art historians will champion what I’ll call the potential for a symbiosis between old and modern painting. And because one will rush to penetrate the ideas of the other, they will unwittingly rally the army, shoot the contemporary wall painting to smithereens, and turn it into a pillar for the next decade of art.”[20]

In the texts that make up Falzum, Ludva does not go to great lengths to transgress the established schemas for detective prose. His protagonists are a pair of police officers who represent different methods for reaching the truth but nonetheless complement one another (Aristotelian logic vs. intuition guided by associative links between seemingly unconnected phenomena).[21] As scholars have often noted, the author respects the trope of inverting the chronology of events (beginning with the discovery of the murdered victim’s remains, retreating into the past, and ultimately unearthing facts from her life that are “crucial to the case” to finally unmask the perpetrator behind the crime).[22] He foregrounds the role of witness interrogations and does not deny the significance of material clues and contemporary crime techniques (although he may downplay them). As a result, he offers the reader all the genre components they “know and love” and, by preserving the hierarchy of values, he (structurally) subordinates all components incidental to these conventions and prioritizes those that play a hand in depicting (revealing to the reader) the social relations of painters, artisans, art dealers, art historians, auctioneers, and curators. The puzzle behind the crime committed in precisely this hermetic (colloquially speaking) and therefore exotic environment continues to expand, thus contributing to the appeal of plot devices. The specific subject matter, meanwhile, allows the author to smuggle in actual news sources on the contemporary state of the art world (which is truly worthy of scorn, if we take Ludva’s word). In this way, Ludva is updating Horace’s maxim: Aut prodesse volunt, aut delectare poetae. Having lost touch with the public in any authentic way, the art world is vegetating on the margins of the collective imaginary, now stirring up feelings only among specialists and potentially nouveau-riche snobs who are only interested in a highly assessed “gallery array of commodities.” The writer therefore conveys reliable art history knowledge through the text’s back doors, as it were, availing himself of ekphrastic devices as well. It is against this backdrop that we can explicate (broadly conceived) issues concerning the relationship between the original work of art and its copy. These themes reference the belief – postmodernist in origin – in the impossibility of defining an absolute paradigm as a stable reference point for an infinite series of replicas, pastiches, and modifications. In the Wall of the Heart, the mandate to revive medieval painting techniques (inspired, in this case, by the iconographic imagery of the famous Czech painting Jan Knap) already opens up a pathway for questioning the limits of the right to imitate the old masters, the function of citations, and allegations that art is derivative or lacks original inventiveness. The stories found in the Counterfeit collection braid these issues into a web of criminal intrigues (let us remember, after all, that identifying the theme of falsification with murder is no particularly innovative novum in the history of the genre). Together, these texts demonstrate that the concept of the counterfeit has not, at the end of the day, been definitively mapped (in an ethical sense as well, for appropriating the ideas of others does not necessarily imply theft or plagiarism). The concept’s meaning encompasses not only “primitive” exchanges of authentic works with their impeccably executed replicas, but also exercises in style that serve to perfect the artist’s skill set, as well as a whole range of essentially literal paraphrases that allude to the continuity of cultural tradition. After all, in these apotheoses of the “eternal life” of the heritage of great art, it is easy to identify echoes of basic theoretical aphorisms supporting (justifying) the dispersed eclecticism of postmodernist painting.[23]

Jan Knap, Untitled

Miloš Urban also explores themes of the counterfeit, although in his approach, the question of how to situate the evolution of artistic strategies along a trajectory of innovations and repetitions provokes axiological anxiety and aesthetic misgivings. The novel Stín katedrály. Božská krimikomedie (“The Shadow of the Cathedral. A Divine Crime-Comedy;” 2003) tells the story of a series of murders building up to an act of vandalism targeting sacral space that reduces Prague’s most important spiritual site to the banal status of the “crime scene.” The book’s protagonist is an art historian named Roman Rops (a surname that explicitly evokes the provocative Belgian symbolist Félicien Rops). Rops is working on the monograph Kamenný hvozd (“Stony forest”), which discusses an extension added to the cathedral in the nineteenth century. Through this protagonist as mediator, the writer (at least in part) subverts the logic of the cathedral’s reconstruction. One character, the stonemason Angelo Fulcanelli (whose surname is also clearly laden with meaning)[24] uses only “original” medieval masonry techniques (as one might suspect) and has this to say about the church:

“You’re just like me. You have a romantic soul. It’s like I’m meeting an old friend. And I’d like to point out, one romantic to another, that just as the original section of the cathedral represents peak Gothic style, so does the new section represent counterfeit Gothic. You will of course be aware that Romanticism, in its fullest bloom, is worth nothing itself, but as a mirror of the whole, nothing can surpass it. Harmony rests within it (…) This murder that took place in the church, I think it has something to do with this.”[25]

Sacral architecture in the Gothic style, despite the best intentions of its designers who “earnestly” strive (as the maxim from Ludva’s novel demands) to produce an authentic effect, lacks the capacity to provoke the desired spiritual response. For it lacks Benjamin’s aura, since the structure is not saturated with internalized religious experiences, but is merely an expression of expert knowledge devoid of emotion. In a holy place of this order, crime does not necessarily coincide with an act of profanation (and according to the murderer, it is no such thing). The ending is shocking enough in the context of genre parameters, but it does not provoke “terror and mercy,” nor does it allow the reader any feeling of catharsis. The perpetrator of the series of murders (or rather, the person “commissioning” the work) turns out to be the archbishop of the cathedral, Father Urban (again, the choice of surname is not accidental, for Urban is known to sprinkle his “signatures” throughout the fictional space of his texts). The murderer is motivated by the need to restore to the Church the social prestige it deserves but has lost due to the encroaching wave of atheism and his disappointment in the protagonist’s “betrayal,” for he had taken the book’s hero as his spiritual son and heir:

“I raised you to be the best holy man among all holy men, an intellectual who could come to the defense of our affairs. Today, everyone makes a mockery of the Church. So I told myself it was high time for the Church to relearn how to inspire fear. (…) And yet, this didn’t help at all (..). Not these shattered statues, nor the pig released into the church during mass, nor even all this monstrous slaughter. You didn’t see any of my warnings. You didn’t see or hear them.”[26]

Auratic experiences do, however, accompany the contemplation of the aesthetics of churches designed by Jan Santini Aichel (1677-1723), the Baroque architect who designed his work at the service of the counterreformation agenda and had a profound impact on the cultural landscape of the Czech and Moravian provinces. It was not, however, this aspect of his enormous artistic legacy that inspired the writer to publish the novel Santiniho jazyk. Román světla (“Santini’s Tongue. A Novel of Light;” 2005). It was a certain belief, in part fabricated and in part based on archival records (in one might call a game of inversion, or a form of play between dichtung and wahrheit that has general become an “identifying marker” of Urban’s fictional writing). The belief maintains that these churches’ designs conceal a secret message. According to this belief, it would require deep knowledge of the Kabbalah, Christian numerical symbolism, and the arcana of the freemasons to decode this message, but the reward would be the attainment of absolute wisdom. The message’s meaning, restricted to a tight circle of chosen ones, is passed down from generation to generation and protected from profanity, even if its sentries must resort to crime to keep it safe. In the community of the initiated, an irreproachable law states that “the end sanctifies the means” (and in this case, we must read sanctification literally). Murders are committed with automatized precision and a near-total atrophy of aesthetic sensitivity. The refined aestheticization of the murders consists of theatrically arranging the victims’ bodies in a set of poses (calling to mind the writing of Thomas de Quincey).[27] The arrangements take on signification (the corpses’ severed tongues suggest ties to the canonization of John of Nepomuk and simultaneously command the message’s addressee, the novel’s protagonist, to remain silent).[28] Aestheticizing murder serves the function of warning those who try “unauthorized” to force their way through the complex “security system” safeguarding the secret message. Martin Urmann, the protagonist and narrator of Santini’s Tongue, who works as a copywriter for a prestigious ad agency, attempts precisely this. He is motivated not by a desire to attain the highest level of knowledge, but by the threat of losing his job. For he has been saddled with an impossible task (in a nearly folkloric sense): in a business enterprise called The Golden Copy Project, he is to formulate a universal slogan “that can sell any product.” Seeking tools to tackle this staggering challenge, he is inspired to contemplate the meaning of Saint John of Nepomuk’s silence (to protect the mystery of confession). In a more or less natural thought process, these themes prompt him to reflect on the saint’s baroque cult and ultimately directs his thoughts toward Santini’s churches, and particularly the church in Zelena Hora, which is built on the template of the five-pointed star (five stars symbolize the letters in the Latin word tacui – “I silenced myself”).

The pilgrimage church of Saint John of Nepomuk in Zelena Hora

Urmann’s pursuits quickly turn into a private investigation. He is accompanied by his helper and advisor Roman Rops, known to us from Shadow of the Cathedral, and Viktoria, a recently graduated architecture student (representing the circle of the initiated) who is fascinated by Santini and dreams of reviving his Baroque-Gothic style. The story obeys the structural parameters of the thriller by endowing its hero with an undefined position that straddles potential victim, detective, and accessory to the crime.[29] His narrative role is not limited to unveiling the truth and unmasking the murderer (as it would in a “classic” crime novel). Against his will, he is embedded in a series of incomprehensible and risky events (“It all started with an accident. Or for a while, that’s what I believed. Today, I am no longer so sure”).[30] He is ceaselessly watched and led onward (“marked”) by the gatekeepers of esoteric knowledge who seem to be omnipotent (within the fictional space of the text). He becomes the target of manipulative actions that on the one hand fill him with doubts and suspicions (heroes of the thriller are often distrustful, although we might say the same of conspirators and police officers for other reasons; in Shadow of the Cathedral, the chief officer of the department of homicide, Klára, falls to the wayside next to Roman Rops, the text’s narrator).[31] On the other hand, these manipulative actions also qualify him for initiation, during which grasping the actual meaning behind the series of murders becomes the indispensable condition for total transgression.

The success or failure (“You didn’t see any of my warnings. You didn’t see or hear them,” Father Urban reminds Rops) of the hero’s engagement in this process therefore depends on his acceptance of the very idea of the right to murder, which loses its status as an unethical deed and becomes instead a tool for rehabilitating fundamental values. This therefore leads to an interrogation of one of the “core premises of the crime novel: crime is a disruption of the ‘world order,’ or rather, in the crime novel, this order will always be inverted.”[32] Urban inverts this premise, as if through a mirror’s reflection. The destabilization of the existing order occurs earlier, and is perceived as an immanent property of the contemporary moment, while the present appears as the domain of an encroaching entropy. Crimes can either confirm entropy or perhaps mark it as a kind of warning to see things from the other side (in this case, the victims would be entirely arbitrary, like in Santini’s Tongue) or as “justified punishment” for a social misdemeanor (here, modernization correlates to the loss of the spiritual dimension of existence). In this way, crimes point the way to a kind of restoration of the cosmos, or a return to a specific moment in the past and its resultant reconstruction.[33] Art that has been preserved in it is original form, and historical sacral architecture most of all, can evoke cultural memories that update axiological certainties that have been lost in today’s world (undeservedly, if we take Urban’s word). Art can also restore to these truths an appropriate number of metaphysical guarantors of immortality that govern the laws of reality.

With bold panache, Urban approaches the genre templates of the thriller, horror literature, occult literature, gothic literature, and even the decadent dandy novel (Rops, who adores pre-Raphaelite painting, thinks of himself as a “latter-day Victorian”)[34] inherited from Arbes and discernible among his contemporaries. Yet this does not eliminate the validity of the antimodernist message mediated by these sensational plots from the reader’s (scholar’s) field of vision. To be fair, he treats all his inter- and architextual sources with a typically postmodernist ironic distance that ultimately demonstrates the contrived nature of narrative devices. The author does not, however, shy away from pushing the borders of good taste (“I stood with my left leg in the monk’s ribs, while my right leg was lodged in the nun’s crotch,”[35] says Urmann as he relates the tale of breaking into the church’s crypts, where he was forced to tread on the rotting coffins). Instead of using tools economically, he chooses an excessive and multilayered proliferation of cultural echoes and reminiscences.[36] We should not, however, identify this strategy with a disinterested experimentation with genre conventions, as we might do in the case of Roman Ludva’s crime stories.

In this sense, both writers offer the reader a compelling cocktail of mystery, suspense and (in Urban’s case) the abject and macabre, enriched (deepened?) with an assessment of the disadvantages of the postmodern world. This world has witnessed the downfall of traditional value systems and a crisis of logocentric epistemology, and is therefore left with feelings of loss and alienation. The distortion of reality, meanwhile, provokes a longing for a former order and transparent cognitive schemas, thereby motivating one to seek out alternative orders. It is not by chance that Lieutenant Kryštof Fridrich, one of the protagonists of Falzum, is fascinated by the regularity of train timetables, and that Josef Hala from Wall of the Heart translates the generalizations of a Latin maxim into a concrete algebraic equation (death=life -> death=the mystery of the image -> life=image). Nor is it accidental that the protagonists of Urban’s novel take equal delight in the incontrovertible mathematical precision of sacral buildings and the medieval, Christian and Kabbalistic mysticism of numbers.

With regard to the twentieth-century epistemological sensibility, Aleksandra Kunce has argued: “These failures to grasp the whole do not point back to the illegible nature of the world, but merely to the insufficiency of our methods.”[37] We can say the same of attempts to revive schemas of crime literature. These attempts allow us, at least “momentarily” or for the duration of the reading experience, to revive our faith in the effectiveness of the “correctly chosen” cognitive path. By limiting representation to an isolated fragment of the world that is bound by a strictly outlined framework and submitted to detailed semiotic analysis (if we can risk the claim, for Mariusz Czubaj has written about the Saussurian provenance of the deductive logic of the crime novel),[38] we bolster this illusion, although these authors (taking their cues from Eco and Dürrenmatt) attempt (and here I am mainly thinking of Urban) to undermine the non-negotiable validity of linear causality (by evoking, for example, categories of contingency or reflections on the inverted logic of insanity, which is a typical device in thrillers about serial killers). They do so in order to provoke “reasonable doubt” in the reader, while offering a repertoire of potential alternative interpretations of events.[39]

To activate this effect that simultaneously counters and extends the parameters of one of the most popular genre forms, it is not necessary to draw from themes tied to art history and to “overcrowd” the narrative with pseudo-scientific asides using niche terminology (as Urban is wont to do) to the point where it becomes necessary to provide subsequent novels with bibliographies that guarantee the reader a certain referential reliability for the information conveyed.[40] The question thus arises: what purpose is served by these countlessly cited biographies of artists, analyses of traditional iconographic systems, and ekphrastic operations? The answer requires, firstly, that we recall the postmodernist passion for citations, palimpsests, the apocryphal and the counterfeit, which will then direct our attention toward those periods in the history of architecture and painting that include “conscious eclectic duplications” within the system of acceptable artistic strategies (already, Santini cited the architectural strategies of the Gothic style, not to mention the builders of the nineteenth-century St. Vitus Cathedral). On the other hand, reflecting on the mimetic or figurative nature of historical conventions in the fine arts open up a discussion on the relevance and potential rehabilitation of realist literary representation. Intersemiotic affinities make use of the belief that we can define the ontological community surrounding the universe of art (in terms of its function, for example) and therefore open up a pathway towards renewing the totalization of narrative (its cognitive, aesthetic, and last but not least, communicative values). Both writers (in keeping with the tenets of postmodernism)[41] discern a remedy for an escalating dissonance between artists (regardless of the materials they use) and their audience. In Counterfeit, Roman Ludva therefore reminds us that “Art is for people, not angels,”[42] and in Wall of the Heart he argues that as a living organism, the painting should narrate a legible story to its viewer.

Urban is able to draw more far-reaching conclusions from the rehabilitation of the narrative potential of all cultural texts. In his novel Lord mord. Pražský román (“Lord Mord. A Prague Novel;” 2008), which is set at the very end of the nineteenth century, he relates the story of a serial killer who pretends to be the ghost figure Masíček, infamous from Prague folklore. The story also concerns Count Arco, a wily aristocrat, pimp, and narcotics dealer.[43] In the constructed world of the text, the count embodies the archetype of the “detective by chance” so typical of the thriller. He falls prey to conspiratorial intrigues as he strolls around Josefov. Josefov is Prague’s Jewish quarter from 1895 to 1914, when it underwent a process of “ghetto clearance” (in Czech, “Asanace”). To put it bluntly, it was destroyed. The writer reminds us of the heated discussions leading up to the decision to rebuild the city. We read:

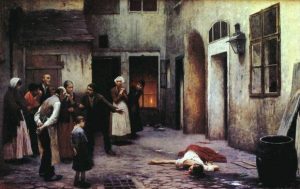

“And then, a cry for help tore away from the open entrance gates; a woman’s voice begged, followed by a yelp, and then suddenly, silence. I came out into the courtyard to join the people who had emerged from nearby homes. Lamps were lit beyond the windows, and in their frames, one dark head emerged after another. Around the wooden annex, a group of poorly attired people had gathered together. There were perhaps eight of them, and they spoke excitedly, in terrified voices. Close by, next to the rain barrel, we saw a girl lying in a puddle of blood. Judging from the position of her body and the unnatural torque of her head you could deduce that her neck had been broken.”[44]

Deceivingly, this narration never seems to diverge from stereotypical descriptions of the scene of the crime so typically found in crime literature, with the exception of the fact that the reader can find a concealed ekphrasis in the passage (and this analytical trope will be reasserted later on in the novel, for the writer offers a list of paintings used to build the narrative). The ekphrasis brings to life the acclaimed painting of Jakub Schikaneder (1855-1924), Vražda v dome (“Murder at Home,” 1890):

Jakub Schikaneder, Murder in the House, 1890

Here, the classic trope of ut pictura poesis entails a specific operation of inversion: the value of the realist (figurative) painting lies in its literariness. Thrillers exploiting motifs of the encrypted language of painting and architecture thus attain the rank of authoritative self-reflexive statements, while investigations in the art world demonstrate that the mystery of the image lies in the stories it inspires.

translated by Eliza Cushman Rose

The structural parameters for crime literature have been the subject of numerous overviews, critical essays, and recapitulations. Yet the renaissance of this literature unfolding today calls for new interpretations. To be more specific, this renaissance takes place in a climate of postmodern penchants for popular narrative and structural schemas, a blending of genre categories, and a predilection for heterogeneous discourses. This very fact should compel us to reflect on the factors contributing to the thriller’s appeal as a genre form that writers so often evoke to provide the reader with a fictional and “deep” statement on the various deficits of the contemporary world. In Czech literature, prose writers such as Roman Ludva and Miloš Urban have taken cues from Umberto Eco and Dan Brown’s tendencies to experiment with well-worn narrative strategies, as well as their local tradition (the tales of the 19th-century neoromantic Jakub Arbes). Following suit, Ludva and Urban embed the templates of the thriller in a broadly organized interrogation of the contemporary condition of art. Simultaneously, using the strategy of “amplified” intersemiosis, they impart an autothematic dimension to their narratives.

[1] K. Čapek, Povídky z jedné kapsy, Prague 1985, p. 110. Translation: E. R. Moving forward, all translations from the Czech are Eliza Rose’s, based on the Polish translations by the author of this article.

[2] For as Caillois argues, in order to expose the perpetrator of the crime, it is necessary to “isolate a specific, human environment from the rest of the world, curtail all external interventions and seepages, rule out a deus ex machine explanation for the mysterious event, and disclose all cues that contributed to the scandal and that must be internalized in order to clarify the course of events. When these conditions are all met, there is nothing that fundamentally differentiates the crime novel from the mathematical problem. (…) At the end of the day, the crime novel ceases to earn its name. At its evolutionary limits, its true nature is revealed. It is not a story, but a task. (R. Caillois, Powieść kryminalna czyli Jak intelekt opuszcza świat, aby oddać się li tylko grze, i jak społeczeństwo wprowadza z powrotem swe problemy w igraszki umysłu, przeł. J. Błoński, [in:] R. Caillois, Odpowiedzialność i styl, Warsaw 1967, p. 191). For an example that supports the thesis on the “mandated” formulaic construction (both thematic and narrative) of the crime novel, we can turn to the words of E. Mrowczyk-Hearfield: “I believe we can provisionally suggest that crime literature is a creative form that centers its concerns around the issue of crime or, more generally speaking, transgression, and the pathway to solving the puzzle of that transgression. This kind of literature does not use crime motifs merely as a pretext for addressing other issues, although it does (depending on the nuances of its subject) often raise moral issues (while consistently relegating them to the background and highlighting the mystery in the foreground). This literature is neither mythical nor sacral. It does not address issues of sin and retribution. It does, however, explore the struggle between good and evil. It is written in a realist mode, and its salient attribute is the explicit formulation of plot and its linear composition consisting of motifs that run in both directions.” (E. Mrowczyk-Hearfield, Badania literatury kryminalnej – propozycja, “Teksty Drugie” 1998, issue 6 (54), pp. 97-98)

[3] See also: „Detektivka (míním zde čistou detektivku a nikoli odrůdy smíšené s románem pasionálním, literárními ambicemi a jinými kontaminujícími vlivy) je literární úkaz stejně jednoduchý jako dejme tomu epická báseň nebo dětská báchorka. (…) Zdá se opravdu, že detektivka už překročila svůj vrchol; byla to jakási přechodná móda. Avšak na každé pomíjivé módě je pozoruhodné to, že obsahuje něco strašně starého.“

(K. Čapek, Holmesiana čili o detektivkách, [in]: Marsyas čili Na okraj literatury (1919-1931, Prague 1971,

pp. 142-143, 156).

[4] R. Caillois, Powieść kryminalna…, pp. 202-203.

[5] A. Gemra, Diagnoza rzeczywistości: współczesna powieść kryminalna sensacyjno-awanturnicza (na przykładzie powieści skandynawskiej),[in]: Śledztwo w sprawie gatunków. Literatura kryminalna, ed. A. Gemra, Kraków 2014, p. 51. Jakub

Z. Lichański makes the direct claim that “the crime/sensation intrigue is only a mask, a convention; authors are in fact describing problems of an entirely different nature.” (J.Z. Lichański, Współczesna powieść kryminalna: powieść sensacyjna czy powieść społeczno-obyczajowa? Próba opisu zjawiska (i ewolucji gatunku), [in:] Śledztwo w sprawie gatunków…, p. 20.)

[6] As Magdalena Lachman argues: “Superficial properties of distorted messaging are mobilized in similar practices. (…). The new application of this messaging ultimately runs counter to its original (and often still prevalent) usage. Writing, then, leads to the consequent destruction of the borrowed material with no prompting to respect its cultural position. This move has a fundamentally provocative nature, for it reveals that every message can be relegated to the level of deactivated material.” (M. Lachman. Gry z “tandetą” w prozie polskiej po 1989 roku, Kraków 2004, p. 191) Teresa Cieślikowska reminds us, on the other hand, that: “The crime novel’s influence on contemporary narrative prose does not lead (…) to the widespread transposition of the crime motif or other crime-related themes. It takes on a more sensory nature on occurs on a scale conditioned by social experience, academic and cultural development, and the full adaptation of contemporary culture in terms of both its triumphs and failures. The discovery of the unknown, the investigation of mysteries, is a foolproof stimulus and like all forms of learning, it will always be an attractive objective. The crime novel relates to this function as a miniature model that expresses and represents (within the realm of possibility), and satisfies a certain set of social needs. (…) What has migrated from crime novel writing into other novel-writing practices is not the subject of crime, but the tendency to assess this writing on the basis of its structural achievements.” (T. Cieślikowska, Struktura powieści kryminalnej na tle współczesnego powieściopisarstwa, [in]: T. Cieślikowska, W kręgu genologii, intertekstualności, teorii sugestii, Warsaw – Lodz 1995, p. 77)

[7] U. Eco, Postscript to The Name of the Rose, in: U. Eco, The Name of the Rose, trans. W. Weaver, New York 1982, p. 525.

[8] See also: “Quite often, the thriller features the very same structural elements that we find in the crime novel. After all, for the scholar, common features can be found in the crime novel (crime, investigation, intrigue, the revelation of a mystery_ and the thriller (the progression of detailed descriptions of crimes and the suffering they bring about). The fundamental difference not only consists of the thriller’s tendency to generate images of the crime. Most importantly, it consists of the presence of some kind of threat to the protagonist’s life and the link between the hero’s fight for survival and the resolution of the mystery, the attempt to solve the mystery for public opinion, and direct confrontations with the antagonist.” (B. Trocha, Między thrillerem religijnym a teologicznym – czyli zbrodnie i intrygi świecie religii, [in:] Śledztwo w sprawie gatunków…, pp. 213-214) Tzvetan Todorov sees the thriller (roman à suspense) as a genealogically mediating form that combines attributes of the “mystery novel“ with the roman noir. (See also: T. Todorov, The Poetics of Prose, trans. R. Howard, Ithaca 1978).

[9] See also: T. Cieślikowska, Struktura powieści kryminalnej…, p. 72. Cieślikowska is referencing Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejak’s monograph Le Roman policier (Paris 1964).

[10] See also: C. Geertz, Blurred Genres. The Refiguration of Social Thought, [in:] The American Scholar, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 165 – 179.

[11] Describing specific aspects of what is referred to as the Scandinavian variant of crime literature and reflecting on the factors that have led to its global popularity, Anna Gemra has noted that the backdrop for Swedish and Norwegian novels “is an often broadly developed portrait of specific customs, traditions, legal and social systems and cultural conditions. In the crime novel, these things are not so drawn out: crime figures as more of a generality. It has what we might call a universal character. It is committed out of revenge, greed fear, contempt, rage, or for more or less enigmatic “loftier” ends. Yet the narrator usually abstains from seeking deeper driving factors, and instead treats the reader to the simplest explanations. Crimes are committed with the very same motives in more commercial, sensational crime novels, although the author (….) lays bare for the reader the mechanisms leading to the final tragedy. We are therefore dealing with a variation we might refer to as the ‘socio-cultural crime novel.’ The courageous escapades and quagmires the heroes live through explain this genre’s appeal and reveal the mechanisms of power, national institutions, business, the justice department, healthcare, and metnal and social stereotypes, etc.”

(A. Gemra, Diagnoza rzeczywistości…, pp. 52-53)

[12] Urban entered the stage of Czech literature “as an author who was associated from the get go with reworking genres, polemicizing (cultural) tradition, and playing with the reader. (…) Particularly in novels whose plot is set in the spaces of authentic sacral buildings, the contrast between the idealized past and the conditions of modern society portrayed on the brink of self-destruction, is foregrounded by introducing an association between these historical, sacral spaces and crime.“ (I. Mindeková, M. Urban: Hastrman, [in:] V souřadnicích mnohosti. Česká literatura první dekady jednadvacátého století v souvislostech a interpretacích, ed. A. Fialová,

P. Hruška, L. Jungmannová, Prague 2014, p. 395).

[13] J. Arbes, Newtonův mozek a jiná romaneta, Prague 2002, pp. 175-176.

[14] See also: “Partly seated and partly lying down, the friend Xaverius rested on a thick saddlecloth on a gurney. He was dressed in a prison uniform worn somewhat open at the chest. The lower part of his body was covered in an old coat from which bare legs poked out. The friend leaned his head backward. He was morbidly pale, nearly livid face turned up to the azure sky. His left hand rested on his chest while the right was bent at the elbow and hung toward the ground. (…) I stood still for a long while, unmoving, and I could no tear my eyes away from the suffering man; for at this moment it seemed to me that I here, just a few paces away, I was not looking at my dear friend (…), but instead someone whose appearance is entirely familiar, yet at the same time, entirely unknown to me. Namely, I had the impression I was staring at the dying Saint Xavier…” (ibid, pp. 236-237).

[15] B. Dokoupil, Vliv E. A. Poea na tvorbu Jakuba Arbesa, “Sborník Prací Filozofické Fakulty Brněnské University“ 1976/1977, p. 37.

[16] It is important to note that Arbes, masked by the narrator’s mediating reflections, does not seek to erase these primary meanings, although he does lend them a universal character, expanding them beyond the painting’s religious explication: “I knew what were the prettiest paintings in Prague’s many churches, but this particular painting grabbed my imagination, no magic spell needed. And yet one would be hard pressed to find a simpler painting! A dying man! How many people have already died and will die in a more interesting and poetic manner than this fellow known as Saint Xavier? Yet when I gazed upon that painting, it never occurred to me to wonder who this man really was and what role he played in advancing humanity or perhaps impeding it; in this painting, I saw but a dying man whose faith was solid as stone, who was able to find his salvation within that faith.” (J. Arbes, Newtonův mozek…, pp. 154-155).

[17] R. Ludva, Stěna srdce, Brno 2001, pp. 157-158.

[18] Of course, the author’s employment of this compositional strategy does not necessarily mean he was directly referencing the Arbes tradition. After all, as Mieczysław Dąbrowski has demonstrated: “The aesthetic of postmodernism samples from two constructive models, and although they are markedly distinct from one another, they share a common root. For both the jewelry box and palimpsest structures stem from the conviction that it is no longer possible to generate a new or original order.” (M. Dąbrowski, Postmodernizm: myśl i tekst, Krakow 2000, p. 133) Brian McHale, however, connects the jewelry box compositional structure with painterly techniques of illusion, such as trompe l’oeil and myse en abyme. (See also: B. McHale, Postmodernist Fiction, New York 2003). Wall of the Heart uses the mise en abyme device to describe the glass walls of a library on which a bas-relief of an open book has been printed on shrinking scales “into infinity”). The device enables the author to reiterate intersemiotic affinities between painting and literature that are essential for the novel’s autotelic layer.

[19] The criminal investigation schema must not necessarily concern deeds legally defined as crimes or, to speak more cautiously, misdemeanors. For every mystery, cloaked behind an incomplete reservoir of information and demanding explanation, offers a chance to apply detective-like methods in order to penetrate the truth. The crime novel, as Régis Messac has argued in the study Le « Detective Novel » et l’influence de la pensée scientifique (1929), “is a story devoted to themethodical and gradual revelation of a mysterious event using rational strategies and strictly defined circumstances.” (Cited in: T. Cieślikowska, Struktura powieści kryminalnej…, p. 67.)

[20] R. Ludva, Falzum, Brno 2012, pp. 109-110.

[21] See also: “Lieutenant, logic is a discipline that is based on so-called cause and effect. One fact produces the next one. Every man is mortal. Aristotle is a man. Aristotle is mortal. Cause and effect (…) Captain, is such a logic really sound? Slivovitz is good. I drink slivovitz. I am good.” (ibid pp. 74, 75) The interlocutor unambiguously protests this claim, but Kryštof Fridrich‘s method of “intellectual stretching” (as described by his supervisor, Josef Rambousek) in investigative work proves to be much more effective than dry “Holmesian” deduction.

[22] See also: Caillois, Powieść kryminalna czyli Jak intelekt opuszcza świat…, p. 169.

[23] For Krystyna Wilkoszewska, the telltale signature of postmodernist painting is the fact that “after the era of neo-avant-garde ‘works’ in the vein of assemblage, fluxus, performance, and so on, the painting has made a comeback. We now find canvases covered in paint, framed, and hung on walls.” (K. Wilkoszewska, Wariacje na postmodernizm, Kraków 2000, p. 196) Scholars call the artists behind these paintings postmodernists, for they “tend to depart from formalism and abstraction and return, often ironically, to mythology, history, and narrative. Their materials are the iconographic ‘treasure troves’ of the past that – once appropriated – accumulate alongside one another on the paintings. It is not unlike the scenario playing out in literary intertextuality: paintings speak among one another. One references another, or perhaps several others.”

(Ibid., pp. 207-208).

[24] Fulcanelli (1839-1953) was an alchemist and occult author known exclusively by his French pseudonym. In light of cultural references demonstrating the fictional nature of the world constructed in Urban’s tale, it seems most significant that his book Le Mystère des Cathédrales (published in 1926) is cited several times in The Shadow of the Cathedral.

[25] M. Urban, Stín katedrály. Božská krimikomedie, Prague 2003, p. 64.

[26] Ibid, pp. 273, 275.

[27] I am referring to de Quincey’s essay On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts, from 1827. In his story Gotické zvonění (“Gothic Bells Ringing”), Ludva explicitly references this work. See also: R. Ludva, Falzum, p. 19.

[28] See also: “In the window (…) the parson stood and watched us, his white face gleaming through the windowpane in the light of the rising moon. It’s no good (…) something here has gone terribly wrong (…). The priest moved not even one millimeter from the window and did not turn his head when we stepped inside of the gray room. (…) I tapped him on the arm and this subtle but harried movement set him off balance. Clumsily, the body sank to the floor. He must have been lying this way before someone set him up in the window. The priest was carefully ensnared in wire that had been twisted into a snug cage. He was tied into this cage to prevent him from falling down. A wire brace around his neck propped up his head in a vertical position. (…) From the wire loop tightened around the wrist and hips, a rod dangled downward, resembling a tail. It curled in an arch down to his ankles, and from there rose up again to the belly, ribcage, and face with its bloodied chin. It ended at the eyes, which were cocked open. (…) A darkness breathed from those eyes, and an emptiness that seemed to waft from the depths of a cave. As I had foreseen, the murderer had cut out the tongue and taken it with him.“ (M. Urban, Santiniho jazyk. Román světla, Prague 2005, pp. 207-208)

[29] Evoking Jerry Palmer’s schema, Mariusz Kraska notes that “three basic indicators determine the identifying marks of the thriller: 1. The existence of a conspiracy perceived as the “unnatural” or pathological destruction of the normative world organized against it; 2. The presence of a competitive hero endowed with special abilities and powers, who is nonetheless a loner and outsider who resembles his antagonists; 3. The significant status of suspense as the narrative’s basic driver.” (M. Kraska, Co by było gdyby… czyli dlaczego powstała political fiction, [in:] Literatura i kultura popularna IX, ed. T. Żabski, Wrocław 2000, p. 145. Kraska is referencing Jerry Palmer’s Thrillers. Genesis and Structure of a Popular Genre, London 1978, p. 100).

[30] M. Urban, Santiniho jazyk…, p. 13.

[31] As Bogdan Trocha writes, in thrillers based on religious motifs (and Urban’s novels belong within this category) the narrative schema “calls for the coexistence of two kinds of investigation: the classical typology led by the police and seeking to expose the perpetrator of the crime using the forensic toolkit, and a second investigation that compliments the first one and seeks to explicate the function of religious symbols present at the scene of the crime and to define their potential role in the event.” (B. Trocha, Między thrillerem religijnym a teologicznym…, p. 223)

[32] W. Bialik, Friedricha Dürrenmatta polemika z konwencją typowej powieści kryminalnej, [in:] Śledztwo w sprawie gatunków…, p. 80.

[33] In other novels by Urban, this dream to turn back time takes the form of a regressive utopia brought to fruition. Sedmikostelí (“The Curse of the Seven Churches;” 1998) discusses restoring the conditions of the fourteenth-century (“pre-hussite”) medieval period, and Hastrman (“Water Sprite;” 2001) discusses restoring proto-Christian beliefs, customs and rites.

[34] See also: “Those artists called themselves pre-Raphaelites and created a brotherhood under the spiritual patronage of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. As adherents of the style prevailing in painting before the advent of the school of Rafael Santi, they proposed a paradigm of art that would have shocked its contemporary society with its awesomeness, sensuality, and dreamy quality, but also with its naivety. In the age of steam, colonial wars, academic realism and the first symptoms of emerging impressionism, such an art would be charmingly anachronistic in its simplicity. To make matters worse, they indulged in something unheard of: equip art with a new and courageous quality, thereby condemning the Avant Garde as a whole. They wanted to create Beauty in an era that has gradually ceased to appreciate such a thing. For them, beauty has become a godhead, and all else must be subordinated to it. And I, in fact, belong to this brotherhood. I am an unfortunate Victorian too late for his time. I belong among the last adorers of their art, and most of all, of the canvases of Rossetti who so stupidly forgot about the twentieth century and all its expressionisms, cubisms, and abstractions.” (M. Urban, Stín katedrály…, p. 38)

[35] M. Urban, Santiniho jazyk…, p. 193.

[36] Marcin Świerkocki emphasizes that excess, akin with transgression and one of the constituting aesthetic categories of postmodernism, “signifies the transgression of a defined border in the sense that it is an escape from a singular and closed system and/or an annexation of foreign territories. Excess therefore also signifies all postmodern forms of multiplicity: all artistic multiplications, copies, permutations and combinations, along with all forms of pluralism (…). Surplus is therefore the only “presence of multiple things at once,” for it simultaneously means excess, exaggeration, going too far (beyond the bounds of convention), and extremeness, or often, the “excess” presence of one thing at one time, as if multiplied in a chamber of mirrors, with its various potential meanings actualized (and multiplied).” (M. Świerkocki, Postmodernizm. Paradygmat nowej kultury, Łódź 1997, p. 73)

[37] A. Kunce, O dwudziestowiecznej wrażliwości epistemologicznej, in: Dwudziestowieczność, ed. M. Dąbrowski, T. Wójcik, Warsaw 2004, p. 115. Kunce is countering the macrological claim to reason that deems itself capable of grasping the whole, which resembles “self-limitations” of the nonconventional investigative methods laid out in the contemporary crime novel that rise out of the “desire to raise doubts and highlight its powerlessness to grasp the epistemological and moral man.” (Ibid, p. 116) This position engenders a micrological sensibility“that would show the disintegration of every whole that has been dragged through chaos, dispersion. (…) In this sense, sensitizing thought – a process that encounters a twentieth-century aspect in its relf-reflexive approach, would veer in the direction of a mind defined by suspension disbeliefs, trusting all shades and undertones, softening contours, quieting its impulses to classify kontury, trustful toward makeshift descriptions that lie close to cultural experience.“ (Ibid).

[38] See also: “The Sherlock Holmes stories are therefore stories that deal less with traces and more so with signs. These texts are manifestations of a semiotic system that, in its paradigmatic version, was first proposed by Ferdinand de Saussure. The essential premise of this pioneer of structural linguistics was his thesis on the monolithic structure of signs that invariably break down into elements of the signified and signifier. This essence of the sign, according to which signifiant is inextricably linked to the signifié, is obsessively expressed in the figure of Sherlock Holmes. (…) the logical rule ordering Holmes‘ world is his faith in the absolute and non-negotiable stability of the sign.” (M. Czubaj, Etnolog w Mieście Grzechu. Powieść kryminalna jako świadectwo antropologiczne, Gdańsk 2010, p. 193) Miroslav Petříček argues that “Murder within the text is necessarily “signifying,” for it is located in the position of the signifiant’s relation to the signifié, regardless of whether we understand the “signifier” as a sign, symbol, or function.” (M. Petříček, Majestát zákona. Raymond Chandler a pozdní dekonstrukce, Prague 2000, p. 188)

[39] It is interesting to note that while they avoid locating Urban within the scope of mainstream sensational genre literature, scholars and critics (perhaps not entirely consciously) accuse him of a lack of normative logic in the way he constructs the sequence of narrative events (whether or not he deserves these allegations is another matter): “The essential problem in Santini’s Tongue remains its ornamental nature, which stems from the absence of a valid causal order. The novel is based on the schema of the incremental revelation of a mystery. It does, however, demand this kind of validity. For the reader must believe the author’s assertion that not only the investigation, but the detective’s sequential steps obey a certain logic: that A comes before B, and that both, of course, are followed by C. This logic must not be covered up by the logic of the outside world, for the provocative work ought to reconstruct its own order of events. One way or another, there must be some kind of logic.” (E. F. Juříková (P. Janoušek), Dvě a jedna je dvacet jedna aneb reklama na Santiniho aneb těžko nositelné boty, in: P. Janoušek, Kritikova abeceda, Prague 2009, p. 298)

[40] From this perspective, Urban’s thrillers, which juxtapose elements and markers of heterogeneous discourses, should fall within the space of so-called blurred genres that seek – as Clifford Geertz suggests – to be “more than a matter of odd sports and occasional curiosities, or of the admitted fact that the innovative is, by definition, hard to categorize It is a phenomenon general enough and distinctive enough to suggest that what we are seeing is not just another redrawing of the cultural map – the moving of a few disputed borders (…). We need not accept hermetic views of Écriture as so many signs signing signs, or give ourselves so wholly to the pleasure of the text that its meaning disappears into our responses, to see that there has come into our view of what we read and what we write a distinctly democratic temper. The properties connecting texts with one another, that put them, ontologically anyway, on the same level, are coming to seem as important in characterizing them as those dividing them; and rather than face an array of natural kinds, fixed types divided by sharp qualitative differences, we more and more see ourselves surrounded by a vast, almost continuous field of variously intended and diversely constructed works we can order only practically, relationally, and as our purposes prompt us. It is not that we no longer have conventions of interpretation; we have more than ever, built – often enough jerry-built – to accommodate a situation at once fluid, plural, uncentered, and ineradicably untidy.” (C. Geertz, Blurred Genres. The Refiguration of Social Thought, [in:] The American Scholar, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 166).

[41] See also: “The nostalgia for a classic hero also indicates an interesting nostalgia for the traditionally structured story, or for the emotionally moving narrative and reliable narrator who was degraded by the Avant Garde and antinovel: this is surely why we observe among contemporary writers an increasing tendency to concede to realism and popular literature.” (M. Świerkocki, Postmodernizm…., p. 72).

[42] R. Ludva, Falzum, p. 172.

[43] Roger Caillois writes more on undermining the detective’s competency (particularly with regard to private investigators or, as we see in the case of Count Arco, amateurs): “Ever since Sherlock Holmes, the detective has remained an aesthete, if not an anarchist, at the very least – a defender of morality or of the rule of the law still less. (…) Generally speaking, his attitude toward society is located somewhat on the margins, like that of a sorcerer or folkloric demon who appears under the guise of a foreigner, cattle merchant, doctor, peddler, or finally, as an invalid: a one-eyed hunchback or gimp. The detective’s mien also possesses – albeit to varying degrees – some disturbing element that is difficult for the social organism to absorb.” (R. Caillois, Powieść kryminalna…, pp. 198, 199)

[44] M. Urban, Lord mord. Pražský román, Prague 2008, p. 144.