The poetics of contemporary texts devoted to poetics – if one may use such a description – stipulate that in the first paragraphs, the author should report on the current situation of the discipline. Such regular self-referentiality (typical as well for other disciplines subject to permanent suspicions of crisis, of which contemporary comparative literature may serve as a good example[1]) should not be particularly surprising to anyone. The scholarly practices of recent years have culminated in a considerable expansion of both the area of poetics’ inquiry, and the repertoire of terms it employs. That particular kind of self-reflexivity in works within the discipline of poetics seems particularly justified in a situation where the tools of poetics – genetically related in an obvious way to the field of literary scholarship – are used to study non-literary or even non-linguistic texts. From the sea of examples illustrating this practice of expansion – already known to readers interested in the problem under discussion – I will cite only the work of Ewa Szczęsna (Poetyka reklamy [The Poetics of Advertisement] and Poetyka mediów [The Poetics of Media])[2] and Ryszard Nycz (Poetyka doświadczenia [The Poetics of Experience]),[3] in whose footsteps I followed in my previous work on the poetics of video games.[4]

This last statement is also a declaration that relieves the present work of the needless – and, more importantly, false – façade of distance or neutrality. I take the position that the form of thought typical for poetics can bring much of value to understanding video games. This position nevertheless demands justification, since one can hear voices suggesting a negative answer to the question whether games are truly open to a poetological reading. A recent issue of Teksty Drugie (3/2015) contained Scott Rettberg’s article “Communitizing Electronic Literature.”[5] Rettberg, the co-founder of the Electronic Literature Organization and a leading light for e-literature, there advances the thesis that in the contemporary world, we function

[…] in a culture of simulations, and many of the most popular forms of entertainment contemporary digital culture has to offer, computer games in particular, do not involve their participants in the sort of imaginative or interpretive experience we associate with literary texts, but instead with the activity of playing and adjusting variables in a simulation. I would not argue that playing a role in a simulation is any less intrinsically valuable than reading a good novel, simply that it is a different type of activity. Planning a city’s zoning and traffic patterns (as a player of SimCity) or leading a raiding party on a dragon’s lair (as a player of World of Warcraft) is a different order of activity from literary reading. While reading is an activity focused on interiority, on building one’s own senses of metaphor, of language, of character, of a world from the materials presented on the page, interacting with a simulation is largely about exteriority, about acting and doing within a world that already has been visualized and imagined by others.[6]

I naturally do not intend to prove that the acts of reading and game-playing are identical– or that both amount to what Rettberg calls interacting with a simulation. The lines quoted above (though not central to his text) deserve close attention, however, since they to some extent appear to represent the views of those who criticize video games in general as a worthless medium. The controversial nature of this statement is particularly visible from the perspective of poetics. I will overlook the fact that Rettberg, by describing the world of games as “already visualized and imagined by others,” seems, perhaps not entirely consciously, to refuse interpretative potential to painting, film, graphic novels and other works of culture of a visual (or audiovisual) type in which the world is clearly presented to the audience in some concrete form.

The problem with the view that emerges from the quoted passage (which, I would like to stress, is only an example here; it interests me as a representation of a certain attitude toward digital media and particularly games) has to do primarily with the illegitimate reduction it performs. The game player’s activity need not be limited to developing strategies, which Rettberg opposes dichotomously to the effort made in reading, which is “primarily imaginative.”[7] A thesis thus formulated proves difficult to defend, chiefly because video games are a very heterogeneous phenomenon, characterized by their enormous range of genres. To a considerable degree, this lack of uniformity hinders – though it does not preclude – making categorical general analyses that can be applied to the entire corpus of games that has arisen. To reduce games to this one dimension – performing operations calculated to obtain the best result while moving through the digital realm – is reminiscent of the arguments used by some participants in the dispute over ludics vs. narratology. Without going into the details of that debate – though the debate itself contributed in important ways to the formation of contemporary studies of games and transmedial narratology[8] – we should remember that some participants in it refused to concede that games are narrative forms. Aside from the fact that the disagreement was largely due to a lack of terminological coordination, the problem also had to do with formulating general conclusions based on particular examples that could hardly be deemed representative.

Video games, on the other hand – particularly contemporary video games, but this is also true of those from previous decades – are diversiform. On the one hand we might consider such games as Microsoft Solitaire[9] or Noughts and Crosses[10] – digital iterations of solitaire and tic-tac-toe. The player’s activities here do not even involve navigation in space; merely completing some basic operations according to strictly defined rules. On the other hand, many video games would best be defined as hybrid cultural texts; in addition to navigation and manipulation of objects within reach, they also afford possibilities for reading or dialogue with another human being. The fact that video games do not leave their users classically understood places of indefinition that are then made concrete by the recipient (which is the gist, I believe, of the accusation that the world of games is “already visualized and imagined by others”) does not mean that they cannot open themselves up to understanding or that they do not demand interpretation. If only for the sake of order, it should be noted that such a hypothesis would go against those philosophical positions that perceive in the act of interpretation the fundamental structure of understanding and an indivisible part of being-in-the-world (as Ryszard Nycz presents that view: “Interpretation in this sense is an inescapable aspect of our ways of making contact with the world”[11]). However, even without referring to how interpretation is understood in the context of Heidegger or Gadamer’s thought, we can name numerous video games that invite complex, sometimes astonishing interpretations.

As an example, we might name the Dark Souls series[12] – almost innumerable articles and internet discussions have been devoted to the question “What exactly is Dark Souls about?”[13] At the start of play, players are given some very meager hints about the plot background, the time and space coordinates in which the action takes place, and the specific goal the game is placing before them – all of which, together with the complex mythology of the Dark Souls world, becomes the object of the player’s investigation, if he feels like investing some interpretative effort in the game. The plot background is not presented straightforwardly in Dark Souls – the player can interpret it based on three kinds of information: conversations with other characters, (linguistic) descriptions of found objects, or a visual map of the game’s world.[14] Obviously the player can simply try pushing ahead without trying to grasp the meaning of the storyworld;[15] however, attentive, precise reading of textual signals can deliver remarkably rich results and open up for the player a whole spectrum of meanings that were not immediately apparent (in this sense the player’s reading is comparable to an investigation based on clues scattered around the world of the game).

A completely different type of example would be the Wiedźmin (Warlock) series,[16] which is deeply immersed in textual material (not only) because its original source material was a book. This game opens up to interpretation due to its singularly intense saturation with intertextuality, discoverable in each of the three installments of the series released to date. As I noted in my articles on these games, intertextual references represent a typical element of such importance in the series that the game’s interpretation as a whole loses a crucial dimension if a whole network of intertexts therein are not taken into consideration.[17] At the same time, we should note that these references are cloaked with varying degrees of camouflage – sometimes demanding an advanced level of reading competency from the player. This is because the authors of Wiedźmin reference a variety of hypotexts – from references to texts of mass culture such as popular songs or films to allusions to high-grade literary registers (e.g. to the works of Poe and Nabokov). Obviously it would be going too far to state that the intertextual dimension represents the most important or dominant aspect of the game. It would also be a mistake, however, to overlook this element and its contribution to the experience of playing the game.

In the context of the quotation from Rettberg cited above, I think an example of a different kind is relevant here. The digital literature scholar refers to metaphor, and thus to one of the oldest and most basic categories of poetics understood as “the aggregate of tools serving to distinguish among and categorize recurring models of literary structures, elements within works or relations between particular elements (names of terms and their definitions).”[18] No one nowadays needs to be convinced of the fact that besides linguistic metaphors, there can also be audial or visual metaphors, or of the fact that metaphors can operate within non-artistic texts as well. As Szczęsna writes: “Metaphors declare an openness to all kinds of signs: linguistic, iconographic, aural, or kinetic.”[19] In the context of video games, it makes sense to ask whether the polysemiotic catalogue indicated by Szczęsna might not need to include an interactive factor – activity on the part of the user that does not fall within the categories of reception or the act of interpretation. This idea is usefully illustrated by the game Flower.[20] I am using this particular example because Flower is one game in which linguistic signs do not figure at all (except for a small number of non-diegetic panels in which the game’s logo is presented or some lapidary user instructions on how to play – not actually part of the game’s universe). I believe that will allow us to productively examine the specifics of how metaphorical discourse can express itself separately from the medium of language.

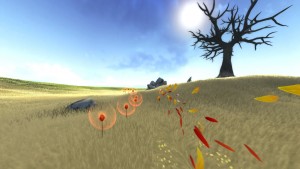

Illustration no. 1. Flower, Thatgamecompany, 2009

Flower presents two diegetic planes – the game’s action plays out in two spaces. The first is an apartment in the city. In the centre of the image we see plants in flowerpots (at first one, while another appears as the action unfolds) placed by a window. At the beginning of play the plant is the only element featuring vivid colours; the apartment itself – like the view through the broken window pane – maintains a dark, depressing colour scheme. This contrast is naturally significant for interpreting the work as a whole.

When the player chooses one of the plants and focuses attention on it by pressing the control button for a longer time (causing the frame to zoom in on the object), the screen slowly begins to go dark, and next the player is transferred to a different narrative space, which can most concisely be described as the realm of nature – the action here begins in a meadow. The frame again displays a plant – either the one the player chose, or a very similar one. One petal breaks off and its movements begin to be controlled by the player. The meadow where the action is taking place may at first appear unbounded, but if the player moves too far in one direction, gusts of wind will force him back to the previous area in space.

Illustration no. 2. Flower, Thatgamecompany, 2009

Although instructions are not directly given, but rather communicated through the interface, the player quickly becomes aware that his task is to approach other flowers growing in the vicinity. Each plant thus visited loses one petal, which then becomes joined to the one being steered by the player. At times an additional effect accompanies the process – the nearby surroundings of the flowers visited take on vivid colours, as if the life force had awakened there. After a short while, the player is steering an entire, systematically growing cloud – or rather: herd – of colourful petals. Each stage in the game places a concrete task before the player – in the first level, she must reach an ancient, withering tree located at the top of a hill. When all of the flowers around the tree have been visited, the colourful cloud driven by the player begins to whirl around and hits the ground in a dense torrent right near the tree’s desiccated trunk. Then a flower grows there (just like the one at the beginning of this stage), and the whole hill becomes covered with vibrantly coloured plants, while the tree instantly grows green and comes to life.

Illustration no. 3. Flower, Thatgamecompany, 2009

The game sequences presented above give us grounds to ask a few questions. Most importantly, what is the relationship between the two areas (the city and the realm of nature) where the action takes place? Does the sequence in the meadow express a certain potential lying within the plant growing in the flowerpot (or in every plant)? Is it a representation of the plant’s dreams (if we agree to pursue an anthropomorphic interpretative path)? Or does the similarity between the two flowers (the one in the flowerpot and the first flower in the meadow) perhaps indicate less identity between individuals than their belonging to the same species? In that case we are dealing not with an individual plant character, but with a reading on a more metaphorical level, referring to the power of nature in general. The answers to these questions become more important when we consider that what happens in the meadow influences the urban space presented in the game. Both the inside of the room and the city itself become more orderly, brighter, and more colourful after each completed stage. This movement from darkness and chaos in the direction of light and order (harmony) seems to point the way to forming at least one possible interpretation of our metaphorical image. In this interpretative approach, the player is embodied – if we can truly speak here of identification – as nothing other than élan vital. A crucial element in this interpretation of the metaphor is the interactive factor (the fact that it is the player steering the life force). If we can talk about a rhetorical message here in praise of nature, the metaphor resonates more powerfully because of the player’s engagement on the side of the realm of nature rather than civilization. The active behaviour of the player Flower confirms in a sense that the voice of nature and the order it creates are a positive value, in contrast with the more poorly viewed development of the world of technology, civilization, and, therefore, human beings. This contrast is not a strict binary, however. The world of culture is not removed or destroyed here; it simply undergoes a metamorphosis, changing under the influence of nature’s healing power. In the final scenes of Flower, however, we see that the city has acquired more colour and life through the victory of nature’s energy – just as the tree became healed in the first stage of the game.[21] We can therefore state that the global meaning of this metaphor resides in the notion that civilization subordinating nature to its needs without regard for her rules leads to disintegration and degeneration. The rhetorical thrust of this metaphor is particularly evident due to its positioning in the interactive context: the player’s actions (which result from decisions governing the way the game is designed) come to confirm the wisdom of the metaphor.[22]

Of course there are other possible interpretations of the action presented in Flower – the constant movement of the multicoloured petals could doubtless be interpreted as, for example, representing artistic creativity or human imagination, which in such a reading would be revealed as the invigorating creative force capable of radically changing the quality of human existence. The variety of possible interpretations remains, naturally, a result of the fact that what we have here is, as Szczęsna would put it, a real trans-semiotic metaphor (as opposed to a lexicalized metaphor – with enduring, i.e., conventionalized, meaning), typified by “originality, openness to interpretation, multiple meanings.”[23]

In an article published in the magazine Forum Poetyki (Forum of Poetics), Tomasz Mizerkiewicz writes that: “It is not entirely reasonable to expect traditional poetics to be able to cope with the tasks connected with [the study of digital texts], but we can expect that its lexicon will quickly become more complex, will to some extent be replaced, and will be challenged.”[24] The example provided by the game Flower appears to confirm this (uncontroversial) thesis. It enables us to ask an important question about the need to expand and update the tools of traditional poetics. If we wish to use them to analyze video games, we must give consideration to the medium’s specific properties and adapt the tools to the context of new textual (or techstual) realities. In this case, the question concerns the category of metaphor and calls for examining interactivity within the range of factors shaping metaphors. Obviously, the purpose of this article is primarily to signal the possibility of approaching the problem using a theoretical apparatus that takes into account the interactive dimension of metaphor, rather than proposing unambiguous conclusions. In the context of future research, however, the interpretation explored above seems promising.

As well as updating previously existing terms, contemporary poetics in its exploration of video games should also develop (and is developing) completely new tools that serve to precisely describe and better understand these digital objects of study. One example of such an innovative category is emergence. In my previous work, I have suggested using this term to designate the effect of shaking the player from the state, typical for video games (and digital communication more generally) of being under the illusion of participating directly in the events shown on the screen.[25] The illusion itself of unmediated participation in the digital fiction is sometimes called immersion – this term (though debatable) is strongly grounded in the current research on games and digital media (and even non-digital kinds of texts).[26] In proposing the category of emergence, I refer simultaneously to the Latin root of immersion (immergo, immergere – to be submerged). If we agree to the comparison of the illusion of participation in a fiction with being “submerged” in it (and that is precisely what the etymology of immersion refers to), then emergence (from the Latin emergo, emergere) would refer to the process of destroying that illusion – to a kind of release from the world of fiction. Importantly, emergence factors (aside from those that occur incidentally, as a result of mechanical or design errors) can be intentionally introduced into a game. A deliberate operation of that type can result in a new, digital version of the strategy of self-reference or meta-fictionality. A clear example of this mechanism of emergence (which can also be read in terms of the Verfremdung effect) is provided by a scene in the game Batman: Arkham Asylum. The device of technical distancing or dis-illusionment presented there is based on the introduction of an effect that resembles a technical glitch but in reality is an innovative form of depicting the protagonist’s perception. Analyzing that device through the prism of immersion and emergence allows us to understand it not only in comparison with analogous devices we have seen in film and literature, but also through its position in the specific context of the digital medium.[27]

I here present emergence as a broad, general category, because I do not wish to repeat myself from previous analyses, but rather to illustrate in an abbreviated fashion how poetics can fruitfully expand its catalogue of concepts to include new tools applied to the specific aspects of the digital medium and not ripped from previous scholarly tradition. Though we must agree with Rettberg when he refers to the clear non-identity of the act of reading and the act of playing, we must simultaneously note that the two processes are not mutually exclusive but can form a complementary whole. The complicated relations between these two, or among these and other factors meriting attention in future research can be seen as a strong feature distinguishing contemporary games and their poetics. From this perspective, to cross out games from poetics’ field of inquiry would be both reductive and unwarranted.

translated by Timothy Williams

A b s t r a c t :

The article shows how video games fit into the spectrum of poetic inquiry and tackles the question of how the tools of traditional poetological studies can be expanded in the context of digital texts. The author considers the interpretative potential that can be discovered in video games. He also points to the specific problems involved in manifesting metaphorical discourse in games without recourse to the medium of language.

[1]See, for example, M. Kuziak, Komparatystyka na rozdrożu? (“Comparativism at the Crossroads?”), Porównania (Comparisons), no. 4/2007.

[2]E. Szczęsna, Poetyka reklamy (The Poetics of Advertisement), Warszawa 2001; Szczęsna, Poetyka mediów. Polisemiotyczność, digitalizacja, reklama (The Poetics of Media. Polysemioticity, Digitalization, Advertisement), Warszawa 2007.

[3]R. Nycz, Poetyka doświadczenia. Teoria – nowoczesność – literatura (The Poetics of Experience. Theory, Modernity, Literature), Kraków 2012.

[4]P. Kubiński, Gry wideo – zarys poetyki (Video Games—Outline of a Poetics), Kraków 2016 [in press].

[5]S. Rettberg, “Communitizing Electronic Literature,” Teksty Drugie, no. 3/2015. Originally published in Digital Humanities Quarterly, 2009, Volume 3, Number 2. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/2/000046/000046.html (last accessed: 25.03.2016).

[6]S. Rettberg, “Communitizing Electronic Literature.”

[7]S. Rettberg, “Communitizing Electronic Literature.”

[8]On the subject of this dispute and its importance in the development of those disciplines, see for example P. Kubiński, “Gry wideo w świetle narratologii transmedialnej oraz koncepcji światoopowieści (storyworld)” (Video Games in the Light of Transmedial Narratology and the Concept of Storyworld), Tekstualia. Palimpsesty Literackie Artystyczne Naukowe (Textualia. Scholarly Artistic Literary Palimpsests), no. 4/2015.

[9]Microsoft Solitaire, Wes Cherry, Microsoft Corporation Inc., 1990.

[10]Noughts and Crosses, Alexander S. Douglas, 1952.

[11]R. Nycz, Tekstowy świat. Poststrukturalizm a wiedza o literaturze (Textual World. Poststructuralism and Literary Scholarship), Kraków 2000, 84.

[12]Dark Souls (series), From Software, 2011–.

[13]See, for example, C. Dahlen, “What ‘Dark Souls’ Is Really All About,” Kotaku, 9 stycznia 2012 r., http://kotaku.com/5874599/what-dark-souls-is-really-all-about, [this and all other internet materials were accessed: 30 January 2016.].

[14]See, for example, T. Battey, “Narrative Design in Dark Souls,” Gamasutra, 25 April 2014, http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/TomBattey/20140425/216262/Narrative_Design_in_Dark_Souls.php.

[15]“Storyworld” is a key term for contemporary transmedial narratology. For more on the subject in Polish, see P. Kubiński, “Gry wideo w świetle narratologii transmedialnej,” Tekstualia, no. 4/2015.

[16]Wiedźmin (series), CD Projekt RED, 2007–.

[17]I have written on the subject in the following articles: “Dystans ironiczny w grach ‘Wiedźmin’ i ‘Wiedźmin 2: Zabójcy królów’” (Ironic Distance in the Games Wiedźmin and Wiedźmin 2: Zabójcy królów [The King-Killers]) in Wiedźmin – bohater masowej wyobraźni (Wiedźmin – Hero of the Mass Imagination), ed. R. Dudziński, A. Flamma, K. Kowalczyk, J. Płoszaj, Wrocław 2015; and “Co wyczytasz pod skórą Wiedźmina 3?” (What Do You Read Under the Skin of Wiedźmin 3?), Ha!art, no. 3/2015.

[18]E. Balcerzan, “‘Narodowość’ poetyki – dylematy typologiczne” (The “Nationality” of Poetics — Typological Dilemmas), Forum Poetyki (Forum of Poetics), no. 2/2015. See also M. Głowiński, “Poetyka wobec tekstów nieliterackich” (Poetics and Non-literary Texts), in Głowiński, Poetyka i okolice, Warszawa 1992.

[19]E. Szczęsna, Poetyka mediów, 85.

[20]Flower, Thatgamecompany, 2009.

[21]This can also be perceived in the game’s audio component. While making the first choice of flower, in the urban setting dominated by dark colours, a quiet, monotonous and rather unpleasant noise of electric appliances can be heard. In the final scenes, when harmony has returned, the background consists of very distinct sounds – cries of children playing, bird voices, an echo of music. All three of those elements (children, animals, and improvised music) also indicate that with the return of nature to her rightful place, the energy of life has returned to the city.

[22]On the subject of the persuasive dimension of video games and their mechanisms, see, among others, I. Bogost, Persuasive Games. The Expressive Power of Videogames, Cambridge Mass.–London 2010.

[23]E. Szczęsna, Poetyka mediów, 92. In this context, it is interesting to remember the words of Ewa Rewers, who notes that “The attributes of Hermes, the patron of hermeneutics and translation, worshiped at crossroads, were resourcefulness and speed, not order and coherence. […] Ruses, traps, turns and deviations – understood literally and metaphorically, practiced and analyzed, play a prominent role in the myth of the origins of interpretation.” E. Rewers, “Interpretacja jako lustro, różnica i rama” (Interpretation as Mirror, Difference and Frame) in Filozofia i etyka interpretacji (Philosophy and the Ethics of Interpretation), ed. A. Kola, A. Szahaj, Kraków 2007.

[24]T. Mizerkiewicz, “Nowe sytuacje poetyki” (New Situations of Poetics), Forum Poetyki, no. 1/2015, 22.

[25]I proposed using this term in my article “Emersja – antyiluzyjny wymiar gier wideo” (Emergence—the Anti-Illusionary Dimension in Video Games), Nowe Media no. 1(5)/2014 [available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/NM.2014.007].

[26]See for example M. L. Ryan, “Immersion vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory,” Postmodern Culture, no. 1/1994; G. Calleja, In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation, Cambridge–London 2011.

[27]I have offered a detailed analysis of this scene in my article “Bergman vs. Batman. Chwyt technicznej deziluzji w grach wideo na tle praktyk literackich i filmowych” (Bergman vs. Batman. The Technical Device of Dis-llusionment in Video Games in the Context of Literary and Cinematic Practices), in Images. The International Journal of European Film, Performing Arts and Audiovisual Communication, no. 1/2015.