1.

“What do you enjoy reading most?” “Biography and autobiography” is what most first-year Polish Studies students replied to this question in the introductory survey I conducted at our first poetics class in 2015. In the current academic year, we also began our adventure in poetics with a conversation about shared and personal reading habits, so I was not surprised to find that not a single person in the group shared Virginia Woolf’s ambivalence toward biography, expressed in her essay “How Should One Read a Book?” over a century ago.[1] Woolf, who professed above all the freedom of the creative imagination and that of the reader, had no doubts about the power of masterpieces and the superiority of modernist writing strategies to the popular (but less and less conventional thanks to the work of Lytton Strachey) kind of biographical work, which belonged to the domain of historians rather than men and women of literature; she considered the reading of biographies to be a kind of introduction to the reading of works of literature:

But a glance at the heterogeneous company on the shelf will show you that writers are very seldom “great artists”; far more often a book makes no claim to be a work of art at all. These biographies and autobiographies, for example, lives of great men, of men long dead and forgotten, that stand cheek by jowl with the novels and poems, are we to refuse to read them because they are not “art”? Or shall we read them, but read them in a different way, with a different aim? Shall we read them in the first place to satisfy that curiosity which possesses us sometimes when in the evening we linger in front of a house where the lights are lit and the blinds not yet drawn, and each floor of the house shows us a different section of human life in being?[2]

The mimesis of biography, the historian or biographer’s position, the documentary nature of the genre, built a convention whose framework could only put restraints on the joy of modernist writing and reading. At the same time, Woolf understood the convention’s power of attraction, feeding on the reader’s desire to learn the truth about a real historical figure (who influenced the history of humanity or was linked to influential personalities), which on the one hand, can be defined in literary theory categories using Philippe Lejeune’s concept of the “referential pact,”[3] and which, on the other hand, Woolf took advantage of in her “biographies” Flush and Orlando. Both of these rather slim volumes can be seen as a formidable form of literary joke: in them, Woolf travesties the referential pact as Lejeune saw it, the mimetic power of biography, the opposite of literary fiction and close (though not identical) to the potential of autobiography: “their purpose is not simple verisimilitude, but similarity to the truth; not the ‘effect’ of reality but its image.”[4] The likeness and image of reality are effects in biography that can be assessed based on the criteria of exactitude (of information) and faithfulness (in meaning); also, “resemblance [is] the unattainable horizon of biography.”[5] Woolf, in writing her biography of Flush, the spaniel who belonged to Elizabeth Barret Browning, and Orlando, a character who wanders across various centuries and lifestyles in Great Britain, not only travesties the genre, but above all evokes the effect of a contiguous biography, yet one located beyond the boundary of the referential pact. Woolf creates a biography without biography (since bios disappears, graphos remains together with exactitude, faithfulness and similarity), that is, a novel (or a long short story) falsifying the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century model of popular biography, in which it was the biographer who, based on his authority, wove a believable story about the life of an important person (usually one who had some influence on historical events).

Virginia Woolf’s ambivalent stance toward biography as a genre is comparable to André Gide’s literary games with autobiography: he does not exhaust or abolish biography, but lays bare the contingent nature of each element in the referential pact, and at the same time, unambiguously comes out in favour of the universalism of fiction, the truth of art – to which he opposes the particularism and inertia of non-artistic texts, journalism and history. He thereby anticipates the tensions that typify twentieth-century literary practice and theory, which wrestled with the rise, flourishing and unquestionable popularity of many genres based on the referential pact, which, on the one hand, most often emerged from the gray area encompassing journalism (feuilleton, reportage) and intimate writings (diary, memoir), and which, on the other hand, took in philosophical impulses that demolished the concepts of “reality” and “reference” from the hermeneutics of suspicion, constructivism, deconstructivism, narrativism in historiography (classical biography being the sister of historiography), and finally the discourse of memory, all of which were accompanied by modernist and postmodernist writing practices: false diaries, multifaceted falsifications and stylizations of journalistic genres or scholarly discourse, drawing primarily from the persistent faith – in spite of the bravura twists, obfuscations and tremors of theory and literature– of successive generations in reality, referentiality, credibility and verisimilitude.

2.

This ferment – the “age of the document”[6] and the age of the deconstruction of strong narratives – was captured by Julian Barnes in Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), taking as its working materials both the biography of the celebrated author of Madame Bovary and the conventions of twentieth-century biography with its many practices, particularly the version in which the scholarly narrator (in the case of Barnes’s narrator, a dedicated amateur) takes readers on a parallel course through both the process of writing a biography and the biography itself, augmenting the role of the narratorial persona and setting it in competition with the subject of the biography (the life of the historical protagonist).

Lejeune claims that when “auto” dominates over “bio,” i.e., in the case of autobiography, the referential pact yields to an autobiographical pact, whose power is not based on similarity (between the real person, the model, and the protagonist of the biography) but on identity, the identity between the authorial, narratorial and model personae. The “authenticity” of autobiography is linked to the authorial signature, even when the story of his or her life is falsified or mythicized. This strategy is used by all biographers who introduce their own “bios” as the story’s framework, thereby augmenting the force of the pact (now a combination of referential and autobiographical), as happens in the many examples that have recently emerged in Poland of “biographical reportage,” which in fact are nominated for prestigious literary awards and honoured as important developments on the map of contemporary literary life.

Barnes, in Flaubert’s Parrot, written before the ethical turn that had such importance for the realm of academic and scholarly biography, which was able to exploit it in the interest of removing the division between objective scholarship and subjective essay-writing (here, representative examples would be the books of Grażyna Kubica: Siostry Malinowskiego [Malinowski’s Sisters], a herstorical “collective” biography of the women referred to by Bronisław Malinowski in his journal, and Płeć, szamanizm, rasa, [Gender, Shamanism, Race], a biography of anthropologist Maria Czapska), revealed the significance of biographers’ particular sources of nourishment in determining the shape of the finished work, each decision to pursue one object instead of another in their research. If Woolf, with her “biographies,” proved that the “unattainable horizon of biography” can be breached by literature, by telling the believable and precise life stories of nonexistent persons or nonpersons, then Barnes draws attention to how the shift between biography and autobiography (or even pseudobiography) does not solve the basic, inherent problem of the referential relationship to reality:

And let’s not forget the parrot that wasn’t there. In L’Educaton sentimentale Frédéric wanders through an area in Paris wrecked by the 1848 uprising. He walks past barricades which have been torn down; he sees black pools that must be blood; houses have their blinds hanging like rags from a single nail. Here and there amid the chaos, delicate things have survived by chance. Frédéric peers in at a window. He sees a clock, some prints – and a parrot’s perch.

It isn’t so different, the way we wander through the past. Lost, disordered, fearful, we follow what signs there remain; we read the street names, but cannot be confident where we are. All around is wreckage. These people never stopped fighting. Then we see a house; a writer’s house, perhaps. There is a plaque on the front wall. ‘Gustave Flaubert, French writer, 1821-1880, lived here while-’ but then the letters shrink impossibly, as if on some optician’s chart. We walk closer. We look in at a window. Yes, it’s true; despite the carnage some delicate things have survived. A clock still ticks. Prints on the wall remind us that art was once appreciated here. A parrot’s perch catches the eye. We look for the parrot. Where is the parrot? We still hear its voice; but all we can see is a bare wooden perch. The bird has flown.[7]

Flaubert’s Parrot is a novel about a detail that “sheds new light on the image of the writer” as a fetish of biography (the parrot is the embodiment of this fetish, and it is a dead, stuffed parrot, above all, multiplied with no original), in which the biographer, looking through the window of the past on behalf of readers and presenting what he sees behind the curtain to them, occupies the most prominent place. Practically this same scene of looking through a window was sketched by Virginia Woolf, in her consideration of the impulses that lead readers to the library shelf with the biographies. Readers are led by curiosity (a voyeuristic pleasure in looking), the desire for knowledge, escapism:

Biographies and memoirs answer such questions, light up innumerable such houses; they show us people going about their daily affairs, toiling, failing, succeeding, eating, hating, loving, until they die. And sometimes as we watch, the house fades and the iron railings vanish and we are out at sea; we are hunting, sailing, fighting; we are among savages and soldiers; we are taking part in great campaigns.[8]

Geoffrey Braithwaite, the narrator of Barnes’s novel, is guided by similar motives. Braithwaite the biographer is obsessive and scrupulous in his research, and simultaneously unskilful and adrift in his personal life. Working on the biography of someone else is meant to compensate, in Flaubert’s Parrot, for a failed love relationship:

Yes Ellen. My wife someone I feel I understand less well than a foreign writer dead for a hundred years. Is this an aberration, or is it normal? Books say: she did this because. Life says: she did this. Books are where things are explained to you, life is where things aren’t. I’m not surprised some people prefer books. Books make sense of life. The only problem is that the lives they make sense of are other people’s lives, never your own.[9]

By drawing a dividing line between “life” and “literature” – though in a simple manner, through the voice of the clumsy hunter for the truth about Flaubert’s parrot, and with distance, since a fictional persona is making the confession – Barnes underscores the meaning-creating power of biography, which though derivative, represents a point of reference for life outside the printed page. This meaning-creation serves to entice biographers with no less intensity than it does readers of biographies – biography, precisely because it is not “pure” literature, need not fear being disqualified on the grounds of its obvious utility. Almost every form of “use” for literature proposed by Rita Felski[10] (the experience of recognition, enchantment, enhanced knowledge, feeling a sense of shock) could be illustrated by a description of readers’ adventures with a biography, but these same categories could be used to tell about the experience of writing a biography – exploring someone else’s life, as well as the necessity of endowing it with a literary, scholarly or journalistic framework.

It should be clarified, however, that the narrator of Flaubert’s Parrot does not combine “lives” and “literatures,” but rather “life” and “books,” avoiding the tangled history of biographism. He himself is writing – from the position of an amateur researcher, of course – a scholarly biography, and his appetite is roused by other conventions and fetishes of biography: the discovery of previously inaccessible archival material that completely transforms our view of the subject of the biography; the erudite interpretation of particular works and demonstration of connections between fictional characters and important people in the author’s life; the discrediting of previous opinions through a display of their gaps and errors of thought; finally, the collection of all available knowledge on the subject of the biography. Barnes mocks each of these in turn, placing his own protagonist in unhappy and compromising situations, but at the same time does not discredit Braithwaite’s guiding desire to get closer to Flaubert – the chronologies of life and work, the bestiary of the writer, the analysis of Emma Bovary’s eye color are masterpieces of the biographer’s craft, which is that of a zealot conscientious to the point of pedantry, who is gnawed at by his cognitive task.

3.

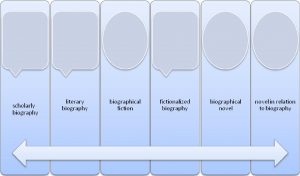

The polar opposites in between which the area of biography is situated are, on the one hand, literariness, and on the other, scholarship, with its traditional sense, spanning centuries, of historiography as an art (ars), and the anti-positivist turn that opened new roads for biographism while closing off others. A second network of tensions that has influenced the transformations (in the twentieth century and more recently) of biography writing, as well as the theoretical problems evoked by biography, consists of the journalistic documentary and autobiographism. This balance of power is explained perfectly by an “archival” work which is also a basic item on the academic reading list in the domain of biography studies: Maria Jasińska’s 1970 book Zagadnienie biografii literackiej. Geneza i podstawowe gatunki dwudziestowiecznej beletrystyki biograficznej (The Problem of Literary Biography. Genesis and Basic Genres of Twentieth-Century Biographic Literature). Jasińska, as a pupil of Stefania Skwarczyńska, was interested in biography as a kind of “amphibious” creature, “both-ish” (i.e., hybrid) in nature and, like Skwarczyńska, she was influence by studies in the theory of genres that grew out of phenomenology, though structuralism so dominates that current of thought that it cannot be compared to Lejeune’s more pragmatist proposal. And yet Jasińska created (in addition to a complex typology of forms of literary biography, placing scholarly rigor at one end and literariness at the other [table 1]) the foundations for thought about a specific type of “biographical pact,” linked with the assertion (frequently repeated throughout her book) that in the end the categorization of a particular instance of (literary!) biography is decided by a series of non-literary factors (social and cultural), above all, an effort to share a common lexicon and mutual expectations between biographer and reader:

Literariness is understood broadly as the total formulated character of the represented world, the approach to organization of language material, and the composition of the work as a whole. “Biographic-ness” is the total shape of connections between the work’s protagonist and historical and geographical reality. This aspect, as the second common factor, besides literariness, in genre differentiation, perhaps dictates that methodological or practical resistance be overcome. Because it must be linked explicitly with a move outside of the autonomy, so frequently underscored, of the literary work, and with entry into the sphere of extraliterary reality. For without historical knowledge, on the basis of even the most penetrating textual analysis, it will be impossible to know how truly qualitative and sufficiently quantitative the protagonist’s links with his original, real prototype are.

The reader, however, counts on those links, often taking up reading the book with precisely them in mind. And the author for his or her part counts on those expectations from the reader. This unwritten but factually existing “social contract” between them defines to a great extent the nature of the represented world in the work, fundamentally limiting the nearly sacred right to fiction, and also strongly influences the type of narration used.[11]

Table 1.

Jasińska’s unwritten “social contract” might be juxtaposed with Lejeune’s referential pact; it is the basis for a biography’s coming into existence with its theme and composition dominated by a concrete protagonist at centre stage, the unambiguous representative of a really existing person (the prototype or model). The “effectiveness” of a biography is based on the author and reader’s agreement regarding the relationship between the book’s protagonist and his or her model or prototype, as well as temporal and spatial realia; it is thus based (as is Lejeune’s referential pact) on similarity to its model (reality), which is analyzed in terms of exactitude and faithfulness. Jasińska, in her analysis of the various criteria of a biography’s “informativity” (or more precisely, a work of biographical fiction’s – this is relatively unimportant, since the typology does not withstand the test of time; on the other hand, the particular problems developed in each chapter devoted to a given type of biography persist as concerns over time), designates the same guidelines as Lejeune. A biography’s informational value is comprised by:

a) The hierarchy, adopted as a convention but in fact obligatory, of events/moments/experiences that are “important” for a given biography, being the compass of the story’s “authenticity,” the first test of the biographer’s level of knowledge and her faithful portraiture of the protagonist. The conditionality of this factor is so conspicuous (firstly, an author’s own rare archival discoveries about persons whose biographies are, socially and historically, previously established, allow revaluation of the hierarchy; secondly, even the simplest experiment, each change of focal length from public to private or vice versa, transforms the hierarchy), that it seems obvious, since it relates to the meaning-creating need for ordering and narrativizing the life of a biography’s hero, while the cognitive framework in which we inscribe the biography are historically variable and culturally varied. And though we find an example that stands out entirely in Serena Vitale’s biography Pushkin’s Button, in which a found file of letters enabled that scholar to study once more the mystery of the great Russian poet’s death in a duel with a French diplomat, and in the process forced an absolute change of hierarchy in the writing of Pushkin’s life (the author of Boris Godunov only appears after several dozen pages of his rival’s life story, and the narrative uses the logic of gossip), and Vitale cannot be accused of ignoring connections between Pushkin and Mickiewicz, it is difficult not to agree with Jasińska when she posits the hypothetical example of a biography of Mickiewicz that leaves out the poet’s ties to Russians, Karolina Sobańska and Towiański as one that would be difficult to accept without reservations. The fact that this very aspect of providing information, signalled by dates, the names of persons and places, particular and concrete data extracted from daily newspapers or letters represents the most frequent target of attack from belle-lettrists playing with biographical convention is another matter. Barnes in Flaubert’s Parrot proposes as many as three chronologies of Flaubert’s life and work, each of them governed by a different hierarchy of “importance,” each treats the author’s life selectively. Woolf in Flush chooses the most important areas in the life of poet Barrett Browning’s spaniel: frantic days spent in the dark rooms of London houses, being kidnaped for ransom, escaping to Italy, flea infestation, and the dreaded haircut…

b) Truth, or rather faithfulness to sources, in practice mixed with what are respectively called eyewitness testimony and common experiences, encompasses – this is an important stipulation by Jasińska, but one which she unfortunately fails to elaborate further on – the external pillars of biography: a set of facts that is the result of scholarly research but does not encompass the inner life of the protagonists. For Jasińska, there is nothing real in the “reconstruction of inner experiences, the domain of, at best, fiction consisting of probable hypotheses,”[12] according to the principles of classical logic, which suggest that analyses of inner life are inarguably closer to literature than historiography, but biography has accepted it as the only possible solution. It is after all the inner life of particular persons: intimate matters, impulses and motivations that led to the choice of one life path instead of another, the way of experiencing the world, the understanding of oneself and others, are all of interest to readers of biographies. Geoffrey Braithwait quakes with curiosity about the thoughts and feelings of his beloved Flaubert. Woolf convincingly reconstructs Flush’s excitements and disappointments (wouldn’t we love to finally find out what animals think about us?). There is thus no biography that would not resonate with some kind of authorial vision of what a human being is: this applies equally to Plutarch, who studied human natures according to the teachings of Theophrastus, and to present-day biographers who abjure psychology and psychoanalysis. Keeping to the level of eyewitness testimony and common experiences results in the transference to the life of a particular figure of an aggregate of psychological and sociological generalities from the historical period and location. Janet Malcolm writes brilliantly on the mistakes and slanders that can occur in epidermal treatments of a subject’s psychology in her book on Sylvia Plath’s “posthumous life” (The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes) diagnosed by biographers, family members, other intimate and distant acquaintances, rarely disinterested or equipped with information adequate to make a psychological or psychiatric analysis. The phenomenon does not, therefore, as Jasińska suggests, involve the relationship between the “unexamined, therefore literary” and the scholarly, but rather the relationship between a philosophical or psychological doxa and its episteme, and the biographer’s preparedness to undertake the risk of interpretation.

c) Credibility and verisimilitude, whose initial premise is the statement that “the reader wants to approach the text in good faith, and the text ‘wants’ to allow her to do so,”[13] and the result – the identification of narrator and author and the display of an emotional, personal connection with the figure of the protagonist. The author’s credentials stand primarily on her demonstration of a base of knowledge – sources (footnotes, bibliography), treated critically by the author/narrator, who thus expresses her professional (scholarly) preparedness for creative work, and enters into a relationship with the model (reality), a verifiable historical and geographical space. This is the skeleton of the biographical pact. Only on this basis – when good faith and readerly expectations are met at this fundamental level – can we, according to Jasińska, build the superstructure of all kinds of “invention,” conjecture, hypothesis, hesitation, to finally open the biography to fantasy, or literary fiction.

4.

Biographies are weighed down by the baggage that young students fresh from high school bring to their university studies in Poznań. Students specializing in documentary and library studies in the department of Polish Studies at Adam Mickiewicz University learn what the art of biography is by reading, among other things, Maria Jasińska’s Zagadnienie biografii literackiej. In the 2015 summer semester they executed a micro-scale research project based on a thought experiment. They were to imagine themselves transported to the year 1968 and answer a dozen-odd questions that required detailed searches of periodical, literary, and historical archives, conducting interviews with parents and friends, visits to museums, specialized reading rooms in libraries, and an active imagination:

Imagine yourself one day (and then month) in your life, if you were sent back in time to the year 1968. First describe yourself and your surroundings, and then the people who are close to you and those you pass every day, as you answer these questions:

a. Where were you born? Where do you live? What are you doing at the moment (are you engaged in other activities besides studying Polish language and literature?)?.

b. What does your room look like? What furniture and appliances are there? What do you see when you look out the window?

c. What do you make for breakfast? Where do you eat lunch? How does your dinner look?

d. What do you wear? What do you feel comfortable in? How do you acquire your clothes?

e. What books are you reading in your classes in (new) contemporary literature? Who are your professors or lecturers? What are they publishing? Where are your classes held? What writers are your contemporaries or belong to the same generation? What classic twentieth-century authors are still alive and publishing? Which have not yet been born?

f. What periodicals do you read? What music do you listen to? What do you watch at the cinema or in the theatre?

g. Where do you plan to spend your vacation? Plan a short trip with friends, a) one for recreation; b) one to attend a literary/music/theatrical festival.

h. What do you read about in the newspaper? What social, political, or economic events move you the most? Which leave you indifferent?

i. Who are your roommates or landlord/lady, if you rent a room or apartment, or neighbors if you live in a dormitory? Do you know them well?

j. Who are your parents and who are/were your grandparents? Do you have siblings? How often do you meet with them? What do you like to talk about? What are you unable to talk about?

k. Who do you go on dates with? Where do you go? What do you do? Who is your boyfriend or girlfriend? What present are you buying him or her for their birthday? (Or: describe an evening with someone you’re close to: a close friend or sibling).

l. What are your plans for the future?

m. What makes you cry, if you do? What makes you laugh til you cry? What annoys you?

n. What do you dream about?

The purpose of this exercise in biography studies was to develop an essential part of the biography-writer’s apparatus, the “reconstruction of the model” (Lejeune), peering into the window of the past and peeking at it through the available materials, taking the first step in the work of illustrating “historical and geographical reality” (Jasińska) – the first step after choosing the protagonist of the biography, but still before undertaking to create a chronology of life and work. The exercise relied on the pursuit of the informational and the referential pact. The task demanded both individual and group work from the class, long hours of painstaking searches in the library (I accompanied the students as they carried out the task), rendered them more sensitive to media (“sources”) and critical in their reading, and tested their imagination in relation to their own knowledge, stories overheard, meanings, and “historical events” in individual memories. It was intended to raise questions about the universality and individuality of inner experiences. In addition, it was intended to be “interesting,” and thus engaging and constituting a challenge, and at the same time I wanted it to awaken the “biographical imagination” in these beginner documentarians – hence the combination of biographical and autobiographical impulses, simplifying the task (most often the students made use of “readymade” life stories, provided to them by those close to them, mothers and grandmothers, in some sense putting into practice the statement by Roland Barthes that History is the life of my mother in the period when I did not yet exist[14]), while also making it more difficult (telling the story of oneself, even “oneself as another,” required a certain level of courage, though working with a persona invented out of whole cloth was also allowed). The end results of the students’ work – multimedia presentations, skilfully made posters, sound and video recordings, even a mini-performance – could have comprised their own exhibition. The group demonstrated that scholarliness is a strong pillar in the writing of biography (though one that remains in potentia). In the second semester, the assignment was to conduct an imaginary interview with a selected writer who was publishing in 1968, using letters, journals, and existing interviews. If the class had lasted another semester, we would have read Woolf’s Flush, Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot, Vitale’s Pushkin’s Button and Malcolm’s The Silent Woman, applying to each in turn the biographist’s credo learned from Jasińska’s Zagadnienie biografii literackiej.

translated by Timothy Williams

A b s t r a c t

The article discusses the most important factors behind transformations in the twentieth-century study of biography, setting as its aim demonstrating the limits on and new paths for biography in relation to three areas: literary practice (working with the examples of Virginia Woolf and Julian Barnes), university pedagogical practice (using the example of the author’s experience), and one of the classic works in the area of the study of biography in Polish literary studies: Maria Jasińska’s 1970 book Zagadnienia biografii literackiej (Problems in Literary Biography), which touches on common ground with the work of Philipp Lejeuene on the biographical “referential pact.” Biography, having been since its inception a hybrid discourse, joining together literariness, a documentary aspect, and a (popular-) scholarly aspect developed in the twentieth century on an unprecedented scale (this tendency is sustained in academic and popular-scientific discourse; the separate genre of biographical reportage also emerged), while the topic also became a focus of interest among modern and postmodern writers who treated the conventions and traditions of biography as pretexts for questions about its philosophical direction.

[1] V. Woolf, “How Should One Read a Book?” in The Common Reader, Tavistock 2013, e-book version.

[2] Woolf, “How Should One Read a Book?”

[3] P. Lejeune, On Autobiography, trans. Katherine Leary, ed. R. Paul John Eakin, Minneapolis 1989.

[4] P. Lejeune, Le Pacte autobiographique, Paris 1975, p. 36. All translations not otherwise attributed are my own—Timothy Williams.

[5] Lejeune, Le Pacte autobiographique.

[6] See Z. Ziątek, Wiek dokumentu. Inspiracje dokumentarne w polskiej prozie współczesnej (Age of the Document. Documentary Inspirations in Contemporary Polish Prose), Warszawa 1999.

[7] J. Barnes, Flaubert’s Parrot, New York 1990, p. 60.

[8] V. Woolf, op. cit.

[9] Barnes, Flaubert’s Parrot, p. 168.

[10] R. Felski, Literatura w użyciu, translated by a team of translation specialists at IFP UAM in Poznań, ed. E. Kraskowska, E. Rajewska, Poznań 2016.

[11] M. Jasińska, Zagadnienie biografii literackiej. Geneza i podstawowe gatunki dwudziestowiecznej beletrystyki biograficznej, Warszawa 1970, p. 42.

[12] Jasińska, Zagadnienie, p. 83.

[13] Jasińska, Zagadnienie, p. 83.

[14] R. Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Richard Howard, New York 2010.