Intersemiotic translation, alongside intra- and interlingual translation, was one of the three types differentiated by Roman Jakobson in his famous article “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation,” and was meant to encompass a translation situation in which a transfer takes place between two different semiotic systems – natural and machine language, literary text and image, image and sound, etc. The development of new technologies, copyright (redefining such concepts as authorship, an original text, and licensing) and marketing strategies relating to products and their sale have caused the concept of intersemiotic translation to slip outside the bounds of its initial definition, but the phenomenon it describes will no doubt continue to intrigue scholars, including in wider contexts beyond what we know as translation studies. It interests me, as well. I intend to consider some translation situations whose point of departure involved an interlingual literary translation, yet where such a translation was not simply the final product, but rather a stimulus toward transmedial derivatives, which together constitute a transmedial translation series. Edward Balcerzan understood the latter concept as a series of literary translations of the same work made by various translators; I propose here to expand the concept to cover a series of translations that interpret the original in the space of various media, or that remain in a dependent relationship to each other, forming mutually interconnected links in a chain of inspiration. What is the function to be fulfilled in such a series by intersemiotic translation? In my search for an answer, I knock on my neighbour’s door, for as we all know, economics is a friendly neighbour of the humanities, and I return having borrowed not sugar or flour but transmedial storytelling and tie-in products.

The traditional hierarchy and temporal order positing that literary works are adapted into the medium of film were disrupted by the idea of novelization, wilfully exploited by producers in the hope of intensifying the audience’s emotional connection with the product on offer – if we were enchanted by the story on the big screen, we can also take in its literary version (though one almost feels compelled to place those words in quotation marks, given the frequently dubious artistic value of the products of this intersemiotic enterprise), the book adaptation of the film. This consumer accessory also serves a pragmatic purpose – as a cribsheet (relieving us of the need to rewind the movie when we want to find information about the plot, character names, etc.) or source for quotations from beloved dialogues, in addition to the emotional purpose of allowing the transmedial receiver’s (the viewer’s and reader’s) bond with the initial product to be cemented and fortified. This type of product promotion does not arouse astonishment, any more than does the extremely elaborate marketing of gadgets that accompanies the release of media works based on narratives broadly understood (most often a film or book, but they may also accompany the publication of a comic book, a music album, the opening of an exhibition, or an aggressive new advertising campaign which becomes an autonomous product in terms of narrative – the vital point is not the medium but rather the potential for brand identification).

These additional products that accompany other media are called tie-ins, and though they can be purchased separately,[1] they remain ontologically linked in a relationship of hierarchical dependence, similarly to a translation with its original or epitexts in relation to the main text. Tie-in products can be narrative or non-narrative.[2] Non-narrative tie-in commodities can include objects for practical use (t-shirts, bags, illustrated mugs), fun gadgets (for example, a Darth Vader-shaped toothpick-dispenser – the toothpicks emerge where his light saber would be), or what are called “evocative artefacts,” which Allison Thompson has written about in the context of Jane Austen fandom – lavender soap or quill pens that aim to create an atmosphere corresponding to the imagined represented world belonging to Austen and her characters: “Jane must have used a quill pen to write with, this fan thinks, so I will, too.”[3] The most bizarre tie-in products include such specimens as ice cream popsicles shaped like James Bond in his Daniel Craig hypostasis, Star Trek-themed coffins, vibrating Harry Potter brooms, or coffee sold by the 7-Eleven chain under the Sherlock brand, which did not refer to flavour, aroma, or even any attractive features of the attached mug in its marketing, relying exclusively on textual presentation, with games and quizzes on the posters and stands selling the product asking “How much Sherlock is there in you?” and tropes from the semantic field typical for the character (“mystery,” “investigation,” “intrigue”).[4]

The second type of tie-in products is the narrative type, based on the strategy of transmedial storytelling, meaning “integrated experiences across multiple media.”[5] This expanded but coherent experience is made possible by “convey[ing] storylines over multiple platforms. For example, on one platform you can follow the main story, on another a minor character, but the overall theme remains the same.”[6]

In 2003, Henry Jenkins clarified that “what is variously called transmedia, multiplatform, or enhanced storytelling represents the future of entertainment,”[7] due to, among other factors, the increasing convergence of media; transmedial additions accompanying the premiere of a film, book, TV series or other cultural phenomenon have now become a natural, that is, basic and essential, element in product strategy. For that reason, as Mittell has suggested, we should also keep in mind the differences between paratextual elements that serve exclusively to promote, arouse interest in, introduce, or invite discussion of the main text (websites, fanpages, trailers, posters, etc.), and those whose purpose is rather further elaboration of the narrative and the world within it,[8] as well as expansion of the field of engagement and experience of the receiver perceiving that narrative.

If, in keeping with these fundamentals, we treat the definition of the tie-in with appropriate comprehensiveness, as a licensed product timed to coincide with the premiere or sale of the main product, then we may define as narrative tie-ins such elements in promotion as book readings or signings involving author and translator (an ephemeral event, but still a product), or video materials (as in the case of the translation of Jakobe Mansztajn’s book Wiedeński High Life [Vienna High Life], which was heralded by a film clip presenting the author, specially produced for the occasion by the publisher, OFF Press) and intersemiotic derivatives that arise from a translation.

These may have particular importance in cases where translations from niche languages are introduced on the market, works by authors unknown to the local audience or by exceptionally demanding ones, and with which an emotional connection needs to be created, or particular care given to recognition value.

When we refer to the latter, a good example of marketing activity bearing the mark of transmedial storytelling using intersemiotic translation is given by the publisher Biuro Literackie. In the years 2007-2013 that publishing house’s new releases included Ukrainian prose, poetry and anthologies in Polish translation. Poems from these editions next became the basis for a contest announced in 2014 called Comic Book Poetry, which set participants with the task of translating a chosen poem (previously translated interlingually) into the medium of the comic book, with the winning entries to be collected in an almanac, Komiks wierszem po ukraińsku (Comic Book Poetry in Ukrainian), released in the publisher’s bookstore in January 2015. In the blurb reviews of the finished product we can read that “when new realities begin to form around poems, […] that means a return to ambiguity, discovering deeper and deeper meanings behind every sentence” (Andrij Lubka) and that “the idea of joining the comic book with poetry is a perfect way to bring poetry back from neglect” (Natalia Marcinkiewicz), so that this transmedial derivative is shown to be an all but indispensable addition, being not only complementary but meaning-creating and ennobling. On the one hand, it remains in a relationship of dependence – also because the poetics of the comic book incorporates words taken directly from the original (translated) poem – and its derivative, translational nature is blatantly underscored; on the other hand, this binding (in the sense of a tie-in) is a function of marketing strategy for a product, which not only demands but in fact requires such an addition in order to fulfil its obligations on the market.

The situation appears in a different light where the case of a literary classic is concerned; in that case, the function of the addition becomes a chance at a new commercial life and possible attainment of the hitherto unreachable target group.

David Damrosch, chair of the Comparative Literature department at Harvard, several years ago stressed the scholarly potential presented by the expansion of the field to include new media in which we find incarnations of motifs and characters from the world literature canon. Although in his reasoning, Damrosch focuses mainly on questions of geopoetics and the universality of what he calls global figures, together with archetypes and motifs originating in or popularized by classic literature and reproduced in other media, which he describes from the perspective of comparativism’s tasks and opportunities rather than those of translation, the examples he notes are no less interesting for the purposes of the current argument, since all of the instances described take as their source some sort of translation (literary as well as intersemiotic).

Among translations of this type, the most intriguing appears to be the case of Dante’s Inferno, including in terms of how its reception defies categories of time. In 2010, the American company Electronic Arts released a computer game called Dante’s Inferno, consisting of a very loose translation of the poem into the language and visual possibilities of the game medium. An adaptation of this type would not itself represent anything particularly spectacular, since games as tie-in additions are a popular product, discussed and classified by media scholars:

Tie-in games typically follow the two options outlined for novels for what narrative events will be told. The first is to retell events from the source material, allowing players to participate in the original core narrative – this strategy is common for film tie-ins, as most games from franchises such as The Lord of the Rings and Toy Story vary little from the original film’s narrative events (…) More common to television tie-ins is treating the game as a new episode in the series, depicting events that could feasibly function as an episode from the series but have not.[9]

What set Inferno apart from other adaptations was its marketing strategy, which proclaimed its product using a special kit released three months before the game. The kit, sold in a box decorated with the same illustration as the game packaging (Dante depicted as a warrior, shirtless, in a helmet) to build brand identification, in addition to a 16-page booklet with images from the game presenting a visual interpretation of the literary classic, an introduction by the game’s executive producer and an academic interpretation of the work, contained a print edition of Dante’s Inferno in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1867 translation. Thus, a marketing addition to a transmedial derivative, resembling those created through tie-in licensing, is in fact nothing other than the genuine “original,” which is itself a translation; indeed, its translation aspect is highlighted by the prominent display of the translator’s name both on the box and in the blurb, which runs as follows:

All hell is breaking loose. Electronic Arts’ thrilling video game Dante’s Inferno has exploded on the scene and this is the book that provides unique insight into its creation. Go back to the source with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s celebrated translation of Dante’s epic poem. Presented in its entirety, here is the foundation and inspiration for the game.[10]

Despite these direct and overt references to the source, perhaps due in part to the increasingly widespread use (as remarked above) of a marking strategy that spins literature from popular narratives, some users reacted with aloofness or even some level of aggression (“WTF is this shit?”[11]) to this source-addition, treating it rather as an incidental by-product of marketing for the game itself, a tacked-on prequel, than as an autonomous literary work meriting twofold consideration and esteem for having been the ultimate source of direct inspiration, the point of departure for subsequent transmedial narratives. A similar effect of hierarchy-reversal between translation and source results from the selling of literary classics in editions licensed as tie-ins to Hollywood film renditions (again, most often based on literary translations of foreign works from the world canon) – on the cover of one such edition, of Anna Karenina, we find the somewhat ambivalent paratext “Now a major motion picture / Starring Keira Knightley and Jude Law.” The typesetting and the presence of the actors’ names and a still from the film might suggest to an uninitiated reader that Leo Tolstoy is the director or perhaps producer of the film rather than the author of a literary work which has undergone adaptation to film. The inclusion of the film’s screenplay as an appendix may further undermine the integrity of the original, and again advance the erroneous notion that the tie-in edition is a “novelization,” an extra added on top of the scenario. Not to mention the apparent illusion that Leo Tolstoy wrote in English:

source: amazon.com

The examples listed above relate to real marketing strategies initiated by publishers. But the metaphor of transmedial (transgenre) storytelling would appear operative in defining less typical situations as well, where the translator becomes the initiator of the production of derivative tie-ins, including those resulting from intersemiotic translation.

After nearly ten years of work, Krzysztof Bartnicki finished and published his full translation of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. The interlingual translation by itself, considering the wealth of languages used in the source, presents an unusually vast area of research for translation studies specialists, but I intend to leave aside the poetics of literary translation for now, in order to focus on the work’s creative potential for transmedial storytelling. A few months after the release of the translation, the Ha!art publishing concern came out with a book bearing the mysterious title Fu wojny (Fie on War, 2012), in whose preface the publisher and author both asserted that it was a collection of translations of ancient Chinese texts on translation strategies, featuring examples from Finnegans Wake, presented in the manner of allegorical fables of war and tactics. The whole work was eventually revealed to be a remarkably deft translation mystification, prepared in consultation with Sinologists (it included, for example, “original” phrases written in Chinese characters), which exposed itself in part through its overly contemporary approach to problems of translation.[12] That published work may be considered a narrative, translational, and translation studies tie-in to Finnegans Wake, of the spin-off type, which takes as the main protagonist of its narrative a side thread from the original work – in this case the very process of translation. The medium also changes (in this case, the genre of text) – instead of a translation of a literary work, we get a pseudo-translation of a work of literary nonfiction. As was quickly revealed, that was only the beginning of the production of transmedial tie-in additions put forward by translators that expanded the horizon for experiencing the base product, i.e., Joyce’s work – in Polish translation or the English original. A year later, a book appeared on the market (this time in fact released by a different publisher, Sowa, but in any case at the author’s behest) entitled Da capo al finne, consisting of a translation of Finnegans Wake (importantly, working once again from the English original) into a musical cryptogram. The book’s title, referencing Joycean wordplay, plays on the musical term “da capo al fine,” meaning from beginning to end. The addition of a second “n” makes it possible to read it in a free interpretation as meaning “from the beginning to Finnegans Wake” or “from A to F,” which in turn might be read half in jest as referring to Bartnicki’s creative and translatorial work – wherever it may begin, it definitely ends with Finnegans Wake. More than 130 pages of the book feature a sequence of letters in small print, without spaces, divisions or other differentiation, which Bartnicki has referred to as a “monobloc”:

source: culture.pl

This text consists in its entirety of eight letters repeated in widely varied combinations, though their sequence is not random, but dictated by the order they follow in the original text. Such a radical reduction might be considered a (risky) textual operation, and its claim to intersemiotic status deemed negligible, were it not for the fact that the remaining letters correspond to musical notes and the entire book is a musical score intended to be played. The translator has himself provided the proof thereof, sharing his own sound recording of Da capo on the website SoundCloud: https://soundcloud.com/gimcbart/, and further asserting that Joyce’s book contains encodings of national anthems and folk songs, not to mention the Imperial March (Darth Vader’s theme) familiar to fans of Star Wars and the waltz from The Godfather. Though a translation of this type does not represent the most obvious forms of the poetics of transmedial storytelling (given that its narration relies on individual letters generating sounds) it certainly does carry out the basic functions of such a poetics – tying in to the base product and expanding the scope of how it is experienced by audiences, as confirmed by one reader (or listener)’s review:

Joyce’s text began to make sound, to make noise with all kinds of different sounds. (…) I felt as if I were descending into the category of the subjective pre-text, into the archetypal language values contained within the sounds emitted, those acoustic tremors of air, deviating from sense and hitting their unknown receiver in a meta-dimension. (…) Bartnicki achieved a deconstruction of “Finnegans Wake” through sound, completing its comprehensive dismantling and simultaneous immortalization. From an impossible text he created a potential, imaginable one.[13]

The tie-in addition produced by the translator is thus shown to be not merely offering an optional experience, but providing a key to the perception of Finnegans Wake, and its presence becomes a condition of reading the base product, through which process the addition adheres to the original principles of tie-in strategy.

Among the many definitions and classifications of intersemiotic translation, the one proposed by Teresa Tomaszkiewicz appears to fit Barticki’s design perfectly, since – rather ironically in this context – it focuses less on the formal aspects of the transfer and more on the need for the transfer to take place:

The sender, when he or she states a certain real or hypothetical lack of perfection in communication by purely linguistic means, expresses a certain meaning, using elements of linguistic code, which becomes encoded differently.[14]

Her thought-provoking formulation, which pragmatically posits that intersemiotic translation occurs where language fails, dovetails with Bartnicki’s motivation as translator, because he makes no secret of the fact that although Finnegans Wake fascinates him, it “disappoints as literature”. He then adds:

Joyce’s plan to convey the voice of humanity misfired. (…) The aesthetic force of the work, or at least of some passages, can nonetheless be affirmed without reservations. Those who cannot understand FW at the level of lexicon or semantics are still able to enjoy the melodic charm of an unknown dialect in recitation, the potency of its rhythm, rhyme, alliteration, onomatopoeia, euphony, nearing the power of song, or music more generally. But nevertheless, in competing for melodic thrills, literature performing the role of music cannot defeat music performing its own role.[15]

Another important task of transmedial storytelling is raising the level of interactivity for the receiver through the presentation of the base narrative (or its derivative in the form of a spin-off) using other, multifunctional forms. In the case of Da capo a musically literate reader is supposed to generate his own interpretations, interpreting pauses, lengths of tones, etc. in his or her own way, contributing successive new links to the chain of tie-in products. This chain was well described by an announcement for the premiere of the remix (Finnegans Wake Remixed, vividly displaying a typical fan fiction mechanism, whereby a work begins to take on a life of its own through the active engagement and invention of its audience) on the Alternator radio channel: “Joyce turned into finnegans wake. finnegans wake turned into letters. letters turned into notes. notes turned into midi. midi turned into mix. mix on the radio [listen, listen!].”[16]

In a conversation after the publication of Da capo, Bartnicki, encouraged by positive reactions to the work (including invitations to collaborate with musicians), said “I think this is the beginning of musical experiments with Joyce.” We may state with certainty that it is anything but the end, not only of musical experiments, but also transmedial ones, since this narrative with its impossible and total language, the still-unfathomed brilliance of its author and its expansion of the boundaries of reading is continuously being retold anew by Barticki, as he offers audiences new products from this series, which remains for better or worse a translation series.

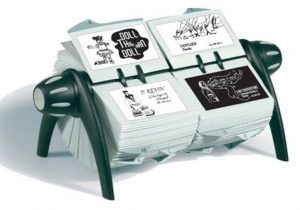

In the meantime, Barticki, working in a duet with a graphic artist, prepared a book in the form of a rolodex, containing over 600 pages. This translation into verbo-visual code[17] required, as in the case of the musical score, that certain selections and reductions be made. The narrative in this version is strongly personalized as it focuses on characters – these figures were taken from each page of FW and events built around them, so that they could each be presented in the form of individual calling cards. Telephone numbers and addresses naturally represent a code maintained in the spirit of the numerical enigmas encoded in the original by the author. The cards also feature original quotations, but as the translator himself has emphasized, these are not intended to be a primary element, but rather to be overshadowed by visual interpretations.[18]

source: culture.pl

Due to the unusually time-consuming preparation process required to produce a single prototype, there is to date only one in existence; it was presented in an exhibition called “Krzysztof Bartnicki & Marcin Szmandra. Finnegans Meet.” The opening was held on December 5, 2015 at CSW Kronika in Bytom, and was curated by Stanisław Ruksza. Curiously enough, this narrative addition is totally analogue in form, though intended for interactive, spatial reception. The slogan that announced the exhibit could serve equally well to announce a typical tie-in in the form of a computer game: “Turn to watch; watch to turn (yourself around) and get to know a whole multitude of bizarre individuals and other oddities of the Finnegan universe.” The two-part structure, on the other hand, is somewhat reminiscent of the Oulipo game of Cent Mille Milliards de Poèmes, since by randomly flipping the cards of the rolodex, the user destabilizes the initial narrative setting and begins to create a new one of their own.

For as long as studies of intersemiotic translation have been conducted, they have faced the challenging task of developing a means of description that would transcend definitional ambivalences (of whether adaptation is intersemiotic translation, to what degree liberties can be taken in such a translation, and so on). I therefore suggest we examine the narrative potential of such translation in the context of marketing strategies of transmedial storytelling, in which we deem each change of format a medium – even if on a micro scale, i.e., genre of text, if that carries with it important narrative changes and remains in a relation of dependence on the original of the same kind as licensed tie-in products have with their source products. Then such translation can be included within the translation series of tie-in products whose function is to tell the same story or spin-off derivatives using other semantic structures for the purpose of expanding the range of available experiences, intensifying the affective potential, aiding brand identification or increasing the interactivity of communication. And if at the foundation of the base narrative we further find a literary translation, the series becomes that much richer and more interesting.

translated by Timothy Williams

A b s t r a c t :

Using examples from literature, film, music, and some that elude unambiguous genre classification, the article presents translation series understood as groups of works (or rather products) interpreting an original work (or each other) using other media. The traditional notion of invoking intersemiotic translation in cases of non-linguistic translation is here enhanced to include the marketing and capitalistic motivations for a variety of translation operations that fall under the rubrics of transmedial storytelling and tie-in strategies for selling products.

[1] The first definitions of the tie-in marketing strategy involved a real relation of dependence, i.e., pre-conditioned sales– to buy one product, the consumer had to buy the other from the same manufacturer (see e.g. Burstein 1962: 68), for example, EPSON printers that only take toner cartridges made by EPSON. Nowadays, however, tie-in refers rather to licensing of authorized products thematically linked to a film, book or other artistic work. They may use the strategy of transmedial storytelling, and thus provide narrative or formal variations on the theme of that work or simply refer to a motif, characters, names or stylistic features of the original work without offering any additional narratives.

[2] See J. Helgason, S. Kärrholm, A. Steiner (eds.), Hype. Bestsellers and Literary Culture, Lund: Lund University Publications, 2014, 28.

[3] A. Thompson, “Trinkets and Treasures: Consuming Jane Austen,” Persuasions On-Line, 2008, vol. 28, no. 2, http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol28no2/thompson.htm.

[4] K. Puchko, “12 Weird Movie Tie-In Products,” Mental Floss, 16.02.2015. http://mentalfloss.com/uk/weird/27406/12-weird-movie-tie-in-products [accessed 05.06.2016]

[5] D. Davidson, Cross-Media Communications: An Introduction to the Art of Creating Integrated Media Experiences, Pittsburgh: ETC Press, 2010, 4.

[6] S. Kalogeras, Transmedia Storytelling and the New Era of Media Convergence in Higher Education, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, 21.

[7] H. Jenkins, “Transmedia Storytelling,” MIT Technology Review, 1.01.2003, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/401760/transmedia-storytelling/ [accessed 25.05.2016]

[8] J. Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling, New York: NYU Press, 2015, 293.

[9] Mittell, Complex TV, 302.

[10] D. Damrosch, “Geopoetics: World Literature in the Global Mediascape,” in: Christian Moser and Linda Simonis, eds., Figuren des Globalen. Weltbezug und Welterzeugung in Literatur, Kunst und Medien, Göttingen: Bonn University Press, 2014, 209-230.

[11] Damrosch, “Geopoetics,” 215-16.

[12] See I. Okulska, “Przekład – wojna – koń trojański,” in: Przekład – kolonizacja czy szansa?, ed. P. Fasta, Katowice: Wydawnictwo Śląska, 2013, 93-104.

[13] http://lubimyczytac.pl/ksiazka/157361/da-capo-al-finne

[14] T. Tomaszkiewicz, Przekład audiowizualny (Audiovisual Translation), Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2008, 73.

[15] K. Bartnicki, Da capo al finne, Warszawa: Sowa, 2015, 4.

[16] M. Gliński, “Polak złamał kod Joyce’a,” culture.pl 27.01.2014, http://culture.pl/pl/artykul/polak-zlamal-kod-joycea [accessed 04.06.2016].

[17] M. Sowiński, “Conrad Festival: dzień trzeci,” Tygodnik powszechny, 21.10.2015, online edition, https://www.tygodnikpowszechny.pl/conrad-festival-dzien-trzeci-30772, accessed 01.06.2015.

[18] See M. Gliński, “Finnegans Wake Rolodexed,” culture.pl 08.06.2015, http://culture.pl/en/article/finnegans-wake-rolodexed, accessed 29.05.2016.