Paweł Tomczok

a b s t r a c t

Introduction

In the present article, I formulate new premises for narrative studies. My starting point is the problematic interpretation of The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz. A close reading of this classic text of Polish modern literature demonstrates that the status of the world described by Schulz is problematic. Indeed, in the present article, I outline a project of alternative narrative studies which could offer us a theoretical language for describing the reality of the intermediary in the process of storytelling. I then compare and contrast my alternative vision of narratology with the most basic premises of the twentieth-century narrative studies and its philosophical foundations, i.e. the Cartesian division between the subject of cognition and reality and, most importantly, the transcendentalist and autonomous sphere of perceptive conditions, such as a priori forms of time and space, logic, language, narrative structures and discourse.1 Such concepts led narratology, and humans sciences in general, into a cul-de-sac; narratology has isolated itself be means of language, narrative, and ideological structures and it is no longer able to create new forms of rendering reality. A similar problem concerns the ways in which we read literature, treating it as a text or a system that is detached from reality and governed by its own rights.

The analysis of literary texts is not enough to expose these premises as false. Although literature often resists structuralist explanations, it cannot itself formulate a coherent system of alternative premises. Today, however, cognitive research and philosophy offer a viable alternative. Since the early 1990s, cognitive science has been moving away from computationalism (i.e. a “mathematical” model of the human mind), instead focusing on what is known as “4E cognition”2 with its emphasis on embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive cognition. Thus, cognitive science follows in the footsteps of different philosophical theories, which are mostly rooted in phenomenology. The second inspiration comes from the philosophy of speculative realism, based on the criticism of the so-called “correlationism,” i.e. the belief in the privileged nature of the relationship between man and the world. Such a post-Kantian model offers new perspectives on the relations between things as well as on the studies of the properties of things-in-themselves. The third inspiration comes from media theories, which question the a priori character of media and the possibilities they offer. Sybille Krämer,3 and above all Bruno Latour, propose a completely new understanding of media as a mediator or a messenger, who relays the message or connects various actants, acting as an intermediary in the processes of negotiation and translation.

In the present article, I shall focus on the problems related to classical (and also post-classical) narratology4 – on its limitations and potential solutions. I refer to the classic texts of Käte Friedemann and Roland Barthes in order to question the assumptions that constrain the manner in which we think about the narrative. However, I also refer to scholars that formulate a new model of cognition and enactivism, allowing us to study narratology from a different perspective.5 Indeed, Marco Caracciolo6 and Yanna Popova7 approach the narrative through the broadly understood category of experience, be it that of the character, the narrator or the reader, referring to Monika Fludernik’s concept of “experientiality,” defined as “the quasi-mimetic evocation of real-life experience.”8 Indeed, Caracciolo, Popova and Fludernik allow us to rethink the duality that defines the twentieth-century literary studies, namely the dual autonomy of fiction and text. Such a dual autonomy should be replaced by different model, which highlights the relations between fiction and other forms of representation as well as the relations between the text and reality at every level of the text and not just at the level of the general and global reference.

The works of Bruno Latour and Graham Harman are the second most important source of inspiration. They allow us to re-conceptualize the notion of reference as well as the relations between actants. Latour defines “circulating reference”9 as a continuous process of negotiating meanings and not as a relation between the finite text and external reality. Although Latour refers to science studies in his theory, his categories may also be used in literary criticism. Indeed, instead of emphasizing the consistency, coherence and autonomy of the literary text, we should focus on how words, events or characters constantly refer to reality and thus treat literature not as a finished and complete work, but as a living and infinite process. Of course, the perspective of the reader, who always discovers a given text step by step, partially, should also be taken into consideration. Indeed, the reader must connect the parts and fragments of the text to something, looking for intermediaries and simulations, through which he can understand individual moments of the text.

Harman is even more radical in his assumptions than Latour, openly declaring that he wishes to practice metaphysics that is realistic and object-oriented as well as speculative (extending beyond the methodology of science). Harman’s theory of objects is an important inspiration for a new theory of narratology. While Harman is known for his a book about Lovecraft10 and theory of metaphor and aesthetics, it is Harman’s theory of a “quadratic” that allows us to discover the hidden, and yet crucial, aspects of both the real and the fictional.

The theoretical inspirations outlined above are eclectic and yet coherent, allowing us to (re)discover the underrated reality, usually replaced by language, discourse or logic. Indeed, they demonstrate that the process of cognition is complicated. It involves not only the “isolated” mind, but also a system or an interplay of various objects that interact with one another. Such an approach to reality also provides us with a new understanding of the narrative – it is no longer defined as a mere linguistic or textual entity, but as a shared cognitive process, which involves the narrator and the reader.11

An intermediary in interpretation

The reader of Bruno Schulz’s Street of Crocodiles12 discovers a confusing space: the narrator of the story describes buildings without roofs, rooms without ceilings, paper trolleys and characters which resemble figures or mannequins.13 In the majority of critical studies, this layer of the story is usually overlooked, as critics tend to focus on the map that is accurately described in the first paragraphs of the text, while the ontological status of the narrative has attracted limited critical attention. The Street of Crocodiles has been read as a description of the socio-economic reality of Drohobych in the years preceding the First World War or as a critique of modern civilization coded in Kabbalistic symbols.14 In both interpretations, the problem of the materiality of the represented world is overlooked, as if the ambiguous status of the described objects had to be obliterated in order for the story to make sense in the social, historical or religious perspective.

However, one cannot simply disregard the materiality of The Street of Crocodiles, because Schulz’s writing points to an interpretation that goes beyond “the real,” allowing us to discover an alternative, artificial and minimalized reality. The city described by Schulz should thus be seen more as a model made of paper or playdough than a real, though rundown, place. Many words in the story can be read metaphorically, pointing to the unstable nature of peripheral capitalism or symbolically referring to religion. However, the text should be primarily treated as a realistic description of a paper model of a city. In the story, the narrator thus walks through a miniature of a city, a model, with shops, plants, trams, trains and figurines which resemble real people. This space allows the narrator to tell stories about different places and people, interpreting their gestures and actions.

What exactly changes when we acknowledge that the city described in the story is artificial? It should be emphasized that I do not wish to question the above-mentioned interpretations. Indeed, Schulz’s text may be read as a critique of modern civilization – though not in the form of a simple description of a commercial district, but rather as a model, a mockup, that both imitates the real and gives rise its own fantasies and dreams.

From text to theory

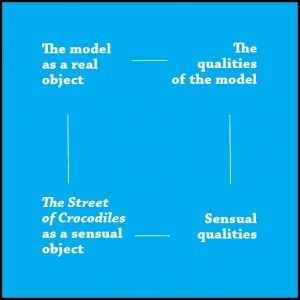

What theory can be employed to describe the status of Schultz’s model? For one, we could simply assume that the story is about the mock-up per se, disregarding the perspectives of a real street or the problems of peripheral capitalism. The mock-up would then function as the story. In such a reading, Schulz would simply describe the inferior nature of “miniature” reality. Schulz’s prose would thus be reduced to the perspective of the teacher of manual arts!15 This method of interpretation is illustrated in Diagram 1. The text leads one to the mock-up, which is the ultimate reference point of the story.

However, the model may also act as an intermediary. In such an interpretation, the model is not the ultimate and final point of reference, but only an intermediate step in discovering the true meaning of the story. The model thus replaces reality – it is easier and more convenient for the author to work with – and, ultimately, the model refers to the reality it represents. The mock-up thus represents a real street; it is a more or less exact “copy” of physical reality.

In this interpretation, I expand on the previous one by adding a new stage, a new layer of meaning, which, however, leads to similar conclusions. Nevertheless, such an “addition” raises questions about the role of the intermediary in the story and the role of objects and tools that render reality more consistent. Schulz’s story reveals the hidden presence of things that make the telling of the story possible, but only if they remain secret and unseen as narrative tools. These structures can function as “affordances”, i.e. what the environment offers the individual.16 In the story, affordances are things that help us organize narration. Narrative affordances can be contingent, but also meaningless, structures that do not belong to the symbolic layer of the story, but allow us to make meaning out of them. They may involve spatial arrangements, juxtaposition of objects, shapes or chronological organization. They can also take the form of maps, diagrams, images and graphs, i.e. representations that carry their own meaning, which can be used as a narrative tool.17

In this case, the model ceases to be just an intermediary and becomes a separate reality that mediates in the process of storytelling. The narrator walks through the mock-up and describes the of world of the model, as if embodying various characters or acting on his own. In order to describe the latter, we have to refer to a number contemporary narrative, cognitive and philosophical theories. Only such a complex theoretical framework allows us to recognize the hidden presence of the narrative mediator and his reality.

From the structuralist analysis towards the materiality of the medium

Roland Barthes begins his “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative,” one of the most important texts in narratology, by saying that “there is a prodigious variety of genres, each of which branches out into a variety of media, as if all substances could be relied upon to accommodate man’s stories.”18 Barthes speaks in this context about the substance, or substances, by means of which stories are perpetuated and distributed (eux-mêmes distribués entre des des différentes). In the English translation, however, the verb “to accommodate” is used. While this translation could be seen as a misreading of the author’s intentions, we should instead read it in terms of the theoretical perspectives it offers: the story needs gestures, objects, material substances and media. The story can also adapt and transforms these substances, but only if it treats them as “fillers” that do not actually influence the content and the structure of the story. Of course, Barthes subsequently focuses on the form of the story, downplaying the role of media substances as something external and unimportant for the pure structure of the story. However, we can question this separation between the material substance (the medium) and the mental form (the structure). Barthes wishes to cleanse the narrative of all material contaminations to discover a structure defined by a system of units and rules. Thanks to such a domestication of the story, he can then claim with absolute certainty that the narrative structure may be found in the story itself – and in this context it means that the structure of the story can be found regardless of its substance.

The structure of the story can, however, be found outside the story itself and its form. Drawing on Bruno Latour’s theory, we can approach the narrative in a non-dualistic way – as continuous medialisation, reification and substantialization. As such, the story is no longer seen as a complicated mental creation, be it of the human mind or discursive structures (some cultural forces), but as a constant process of referencing things and substances that structure the story. The story is thus no longer seen as a dualistic entity, in which the substance of the text and its structure (the combination of its elements) are separate.

In such an alternative reading, the story becomes complete only if it is accommodated by means of a substance; it cannot exist in a mental version prior to its “externalization,” because throughout the process of its creation it depends on articulation, be it by means of the body, gesture or environment (in the case of oral literature) or by means of recording systems (in the case of written narratives).

Barthes rejected the materiality of the intermediary, concentrating on formalist and structuralist approaches to the story. At the same time, he also influenced the future advances in narratology, including transmedia narratology, according to which the content of the story can be expressed in different media. Thus, the active role played by various substances, such as the body, tools or environment, in the construction of the story, seen as a continuous circulation between various elements of the environment, was obliterated.

The medium of narratology

The concept of the medium has been present in contemporary narratology for a long time. Käte Friedemann comments on the “medium of storytelling” in her theoretical study on the role of the narrator in epic, stating that the pure medium of events, defined as the one who evaluates, feels and perceives, is an abstract notion composed of different forms of presenting the narrator in a certain role.19 Narrative mediation thus takes the form of the narrator who mediates between the narrated world and the listener or the reader. This medium is an abstraction; it is a set of rules used to evaluate, perceive and experience. It usually takes on a human form, but in fact it is defined by abstract rules.

Friedemann’s observations have proved important for the twentieth-century formalistic and structuralist theories. The narrator is depersonalised and deprived of human characteristics. Instead, abstract textual terms are introduced, triggering the discussion of the autonomy of (not only narrative) texts. Such an approach in which the narrator is detached from human psychology and the text itself is isolated from the actions of specific people made it possible to construct a vision of an autonomous language, discourse, or code that function as independent entities governed only by their own rules and own history.

Such an autonomous approach became a dogma of the twentieth-century philosophy and human sciences. The language was to be governed by a logic resembling universal grammar. This disembodied and non-contextual system was seen as certain and unquestionable. Indeed, an autonomous approach branched out into a number of theories, from logic and universal grammars to autonomous discourses. In each version, however, the emphasis was on establishing a separate world that would be independent of the natural and social history of man and his environment. Such entities were transcendental in nature, they exceeded reality but at the same time had power over it, as evidenced by Wittgenstein’s early philosophy, Chomsky’s generative grammar,20 and structuralism and poststructuralism. All these philosophies proclaimed the absolute power of language, arguing that everything should be interpreted in terms of an autonomous reading, text or discourse. A similar thought pattern can be found in attempts to search for a historical a priori of knowledge, as exemplified by Michel Foucault in the 1960s.21 These theories waged a war against the subject. The subject of cognition, the author, the narrator or simply man were to be subjected to deconstruction and analysed in terms of textual practices or grammars. The subject was to be defined only as a grammatical subject. While I do not question the need to criticize human sciences, limited by the narrow definition of man developed by modern European philosophy, I see the rejection of humanism by authors proclaiming the primacy of text or grammar as a profound sign of what Bruno Latour defines as the “modern constitution,”22 i.e. the separation between the world and man, the separation between the senseless physical reality and the humanist world of man. This division is so deep that even epistemological attempts to heal it are futile. The autonomy assigned to language, text or narrative is only a sign that this division deepens. In a situation in which man feels increasingly threatened by imposing naturalistic explanations, a new sphere of absolute autonomy opens: the autonomous world of language or text that has absolutely no ties to reality. Latour not only criticizes this division, but also shows us the way out by incorporating autonomic elements back into the network of relations with the world. Instead of sharp divisions, Latour proposes a model in which actants interact with one another through various mediators.

Is the intermediary real or abstract?

The multi-layered mediation that Latour often writes about can offer an alternative to the narrow concept of the medium found in traditional narratology. What is the difference between the two? Käte Friedemann, as well as Franz Stanzel who further develops her intuitions, seem to view the intermediary in realistic terms. However, Friedemann reduces the status of the medium to that of an abstract entity. Stanzel, on the other hand, observes that “every time we convey a message, every time we make a report or tell a story, we meet the intermediary (Mittler) and at the same time we hear the voice of the story-teller.”23 The real intermediary is quickly replaced by the Kantian medium of the cognizing spirit (Medium eines betrachtenden Geistes), in keeping with Friedemann’s approach. Such a realization is for Stanzel the starting point for the reflection on narrative mediation understood as the a priori possibilities of the mind or, in fact, the text. Indeed, Stanzel’s typology of narrative situations is to constitute a closed and continuous circle of forms,24 which vary only as regards their internal possibilities. Stanzel wants to limit and contain all future possibilities and new narrative forms, which means that he also wishes to restrain the creative potential of literature. Such an approach is characteristic for transcendental thinking, which often seeks to determine the internal limits or impassable barriers of the human mind.

The figure of the intermediary, the voice of the narrator, can be also understood in a different way. The Kantian tradition conditioned our understanding of the medium as something non-physical, transcendental and non-material. Of course, we should remember about critics such as Friedrich Kittler, who emphasized the materiality and physicality of various media and their impact on people. However, eventually Kittler focuses on searching for the technological and medial a priori,25 thus once again sacrificing reality for a notion that determines the understanding of reality. At this point, it is worth recalling seemingly simpler and more “mundane” theoretical approaches. According to Sybille Krämer and Bruno Latour, the mediator should not be conceived of as an abstract notion or spirit (even “material spirit”), but as a real actant that mediates between two other actants.

Krämer analyzes various medial theories as an a priori condition for connecting with the world. She criticizes the belief in the omnipotence of media held by most media theorists of the second half of the twentieth century. Instead of a transcendentalist understanding of media, Krämer analyses the message and the messenger, defining the latter as both a real person and as someone who has to disappear so that the message can be transmitted. Media are seen as invisible intermediaries that form connections, creating the illusion of direct communication. Krämer draws on various marginal philosophical theories and thinkers (they are described as marginal, because they address the complicated nature of media that does not fit into the modern European philosophy), including Walter Benjamin with his theory of magic and language, Jean-Luc Nancy, Michel Serres and Regis Debray. Indeed, Krämer wishes to construct a model of communication that accommodates both the materiality of the medium and its disappearance or absence.

This dialectic movement of appearance and disappearance, presence and absence, materiality and immateriality is important for the theory of storytelling. The narrator, the real oral narrator whom Benjamin describes in his famous essay, has such a status. He is physically present, he tells the story by means of his body, voice and gestures, but at the same time he disappears so that the story can appear. Indeed, the real narrator is caught up in a game of overt presence and secretive absence.

In his numerous studies on science, Bruno Latour offers not only a new perspective on life in the laboratory, social conflicts between scientists or the problem of recording the studied reality into formulas accepted by scientific journals, but also formulates a completely new philosophy. According to him, the world consists of actants who enter into relationships with each other, usually through other actants. These relations have the character of mediation, negotiation and translation. Not only people, but also non-human entities (animals, things and loosely-defined objects that enter into different kinds of relationships) can be actants and mediators.

How can we define narration drawing on Latour’s actor-network theory? The story no longer needs to be defined by one abstract narrative medium, but opens itself to the multitude of

different actants involved in its construction. Storytelling is thus seen as a process of engaging various mediators, people and things, on which the possibility of building various references is based. As in the case of science, which relies on a circulating reference, literature uses various storytelling tools to shape reality. Various ways of representing reality, recording techniques and visualizations, thanks to which reality can be textually represented, are all such intermediaries. Instead of a simple relation between text and reality, we are dealing here with complex processes of translation and mediation, which “capture” reality in language or narrative. This process applies to texts that refer to reality and fictitious works that imitate such actions.26

Cognitive narratology

The cognitive approach to narrative dates back to the 1960s, as exemplified by the abovementioned book by Monika Fludernik and numerous works by David Herman.27 These studies demonstrate how various cognitive linguistic tools and, to a lesser extent, logical tools can be used in narratology. However, it is only thanks to a new cognitive paradigm that new narratology can be established as a field of study. Indeed, 4E cognition, which refers to embodied, embedded, extended and enactive cognition,28 provides an alternative to the traditional approach to cognitive science. Indeed, cognitive science in the past placed much emphasis on a “computer” approach, in which the human mind was treated as a program that could be described by means of algorithms. The activity of the mind was then associated with processing, learning and coding symbols and new information. Computational cognition thus went hand in hand with generative linguistics and various grammars. In all these projects, the mind was perceived as something independent of the body and the environment.

In the 4E cognition framework, the mind is integrated with the body and the environment, in its physical, social and cultural understanding. Together, the brain, the body and the environment create a system, a gestalt, whose elements are interconnected. This means that cognition is no longer limited to the activity of the brain or reduced to computational processes. Indeed, the mind is associated with the body, various tools, extensions of the body and the mind, as well as various external objects.

When applied to narratology, 4E cognition opens up new uncharted territories. In his previous research, Alan Palmer emphasized the opposition between internalist and externalist understanding of the mind in the analysed literary texts.29 In the recent years, two books on the intersections between narratology and enactivism have appeared, namely Marco Caracciolo’s The Experientiality of Narrative: An Enactivist Approach (2014) and Yanna B. Popova’s Stories, Meaning, and Experience: Narrativity and Enaction (2015). In both cases, authors focus on the category of experience which connects the reader, the narrator and the characters. It is the active reader, and their experiences, who generates the effect that a given story creates new experiences. According to Caracciolo, such experiences can cross the boundary between fiction and reality, venturing into a sphere of emotional engagement that simulates various events, actions and experiences.30 This simulation is both mental and physical, involving the experience of space. Simulation is based not only on the text itself, but also on the use of memory traces that the narrative activates. Yanna Popova also refers to enactivism, but focuses more on the narrative itself than on the psychology of the character. In her theory, the story does not only “happen” in the mind but in the interaction between minds.31 Indeed, Popova does not reduce the narrative to abstract textual structures such as the plot, the character or the narrative; instead, she proposes a holistic understanding of experience that does not differ from the actual experiences of the participants of in the act of communication.

Naturally, such a new cognitive approach is also associated with theoretical trends which focus on the body, space, media as well as social and cultural environments. All these various philosophical theories provide an alternative to the Cartesian subject, but also to the methods of questioning the model of the conscious subject which see the mind as independent and isolated (from the body and the environment). Such models also defined the basic assumptions of classical and postclassical narratology, which focused primarily on the text and even subjected reality to the categories of textuality or discursivity. However, contemporary narratology demonstrates a different approach, combining various alternative traditions of the human sciences. An example of such a critical text is of course Walter Benjamin’s “The Storyteller.” Benjamin defines the story as an activity that is related not only to the voice, but also to the body, gestures, social function, space and human life.32 A metaphor of craftsmanship creates a nostalgic impression, implying that, as an archaic art form, the story disappears due to civilization changes. The historical point of view exhibited in Benjamin’s essay, however, is in keeping with the anthropology of the story. We can translated Benjamin’s observations from the discourse of melancholy to the discourse of change, with its focus on new media and new narrative tools. Indeed, we can say that the new media extensions of the mind act as effective storytelling tools, as if they were an extension of the hand somewhere in the distance. The voice of the narrator can reach it thanks to new technologies.

Speculative realism

Another context that can revitalize narratology and transform the entire post-Kantian philosophy is speculative realism, especially as evidenced by the works of Graham Harman and his theory of the quadruple object.33 Harman distinguishes between sensual objects and real objects as well as sensual qualities and real qualities. These four categories interact with one another. The most important element of this philosophy for us is that Harman defines real objects as objects that withdraw from all experience. Also, we must remember that the scholar argues for indirect causation, which means that real objects are never related to other real objects, but only relate indirectly to each other through the other three categories.

Harman defines real objects in reference to Heidegger’s notion of ready-to-hand. According to Heidegger, we only notice the ready-to-hand relationship when the tool breaks down. Harman furthers this concept, arguing that real objects must withdraw in order to make room for sensual objects (this is how Harman refers to Husserl’s intentional objects).

Harman’s object-oriented philosophy is particularly well suited to describe the reality of The Street of Crocodiles. In the process of reading, we get to know a sensual object called The Street of Crocodiles. We learn about its sensual qualities, including what various things look like and how different people behave. However, we also discover that many qualities of various objects attributed to them by the author do not create consistent objects, as if other objects and other qualities were present in the story apart from sensual objects. Indeed, the qualities and the objects which they characterize do not “match.” For example, such qualities as being made of paper or of plastic or undergoing wear and tear do not usually characterize trams. Therefore, in the reconstruction of the structure of this story, we should take into account the real object, the model or the mock-up, and its real qualities.

In accordance with Harman’s theory, the diagram of the story could look as follows:

Harman also describes the tensions between the four categories, constituting four poles of the square. The tension between sensual objects and sensual qualities is characterized by time. Time is defined as the time of the story, i.e. the time during which one learns about the subsequent events which occur in The Street of Crocodiles. The tension between real objects and sensual qualities is characterized by space. For Harman, the paradigm of space corresponds to broken tools. Indeed, in Schulz’s story, space becomes problematic when sensual properties “break down.” Unable to construe a coherent object, they reveal their artificiality or materiality. The tension between the sensual object and the real qualities is characterized by essence. At this moment, the essence of The Street of Crocodiles is revealed as something artificial and “cheap” – made of paper or plastic. Finally, the tension between the real object and real qualities is characterized by eidos: while the essence of the mock-up is revealed to be something artificial, it still gives us access to reality that is withdrawn from view. Indeed, the complex process of mediation and metaphorization conceals a different, hidden, reality.

When analysed within Harman’s theoretical framework, Schultz’s story takes on a completely new meaning. It is no longer read as a critique of contemporary peripheral civilization of “cheap” modernity, but as a complex play of various objects that simultaneously reveal and conceal their presence. The real or imagined model of the city gives rise to a complex play of meanings.

Towards the speculative-realistic poetics of narratology

Structuralist narratology wished to discover structures, grammars, and rules that are hidden underneath all texts. In turn, they would allow us to generate all possible stories. In such an understanding, what is hidden in the narrative text is not external to the text. The narratologist simply breaks or discovers textual codes. The twentieth-century studies on the role of the narrator were similar in nature. The author, the narrator or the protagonist were reduced to a narrative function and discussed in terms of the personal and the impersonal mode.34

In realistic poetics, however, the point is to draw attention to the hidden and withdrawn objects of the story. Symbolism gives way to real presence, without which the narrative would not be possible. These objects do not have to be described in the story per se, but they nevertheless function as mediators and things that allow one to tell the story. Thus, the reading of the text must go beyond the text itself, towards the things and substances with which the text remains in a complicated relationship. Importantly, the text as a whole does not refer to an entity that is represented by the whole text. It is crucial to recognize the circulating reference between different words, situations, figures and real objects that act as latent intermediaries of the story. These objects are never apparent or easily perceived. They are never explicitly described. They do not function as sensual objects. The reader discovers them through speculation, deciphering metaphors and allusions.35

What is thus the status of the author or the narrator of the story? Structuralism clearly distinguishes between the author and the narrator. Indeed, the narrator is treated as a purely textual being, which has nothing to do with the psychology of real people. Enactivist narratology offers a different approach. Caracciolo and Popova treat a real and a fictional story in the same way, because both stories engage (with) the body and the environment. Both scholars also point to another important narrative category, namely simulation, but define it as mental simulation only.36 However, simulation, especially narrative simulation, can be embedded in space, things and the body. An example of such simulation can be maps, and various markers, which are read as meaningful. Strategic mock-ups, with marked positions of different units, are a great example. Such mock-ups do not so much trigger (indeed, Caracciolo uses the category of the trigger very often) the constitution of consciousness, but provide a foundation for object-oriented narratology. They allow us to create stories that take into account different, and sometimes conflicting, consciousnesses and points of view. Such a narrative definitely cannot be reduced to the sphere of the mind, but needs to embrace the body, space and environment. Reading involves a similar process. Indeed, Caracciolo devotes a lot of attention to this subject, writing about empathy, simulation, the reader’s reactions and their ability to combine their own past experiences with the consciousness of the characters. Still, Caracciolo does not really comment on some critical moments in the reading process; for example, when the reader has to not so much imagine but visualize some textual objects (in other words, when the reader has to draw, describe, order or sketch something). During such critical moments of visualization, we encounter something that is written in the text but is not limited to the sphere of the mind or memory. Indeed, this “something” makes the reader resort to diagrams, tables, mind maps and even characters’ lists in order to understand the story. Such tools are used in the processes of writing and reading. They are withdrawn and hidden in the literary text, but they can be unearthed and reconstructed.

Summary

In conclusion, I have discussed different critical approaches, because I believe that only a combination of seemingly distant theories allows us to move away from structuralist narratology and transcendentalist epistemology, which constitutes its foundation. New narratology should be holistic in nature, allowing us to speak even about the most general problems (indeed, Harman’s latest book is subtitled A New Theory of Everything). Only by questioning the most basic axioms, we can expose them as limiting and outdated. Indeed, otherwise, criticism of one aspect of transcendentalism will result in defending some other aspect of it. For example, the criticism of subjectivity will boil down to the criticism of discourse or language, which are as isolated from reality as the subject.

So what are the conclusions of this comprehensive reevaluation of narratology? I shall recapitulate the most important points and present my findings.

First of all, instead of emphasizing the autonomy of the text, language or discourse, we should study texts in the context of a network, in which various actants interact. It also means rejecting all claims to establish discursive or media a priori, which can control man and other objects. Instead, we should analyse the networks of mediation and negotiation in which the actants are entangled.

Secondly, we should analyze the narrator, as well as other textual functions such as the focalizer,37 in keeping with the principles of psychology. Instead of trying to reduce the narrator or the focalizer to language (so that they function as grammatical categories), we should see them as embedded in the human body, which experiences, feels, observes, thinks, and makes culturally conditioned judgments.38 Perhaps a new (anthropological) definition of the one who speaks in the story could look as follows: the Focalizer – the Affectator – the Narrator – the Evaluator. The narrative subject would then be a combination of various cognitive possibilities, including the body and the environment. The respective narrative “levels” could also influence one another in the same way as, for example, culture influences biological perception.

Thirdly, we should remember that the real elements of the story are often withdrawn. By “real elements” I refer not only to reality, as the subject of the story, but above all to real mediators, i.e. objects that allow us to tell the story, but are never its subject. They are hidden in the story. Similarly to ready-to-hand tools, their presence remains unnoticed as long as they do their job.

Indeed, combining enactivism, speculative realism, the actor-network theory and media theory allows us to redefine narratology, rediscovering that what (post)structuralism and transcendentalism has obliterated. Only such an approach marks a true turn towards things.39 Indeed, things play an active role in constructing reality, be it in its human, mental or spiritual dimension.

translated by Małgorzata Olsza

In this article, I formulate new premises for narrative studies. Classical narratology was based on a mentalist paradigm. It reduced the study of narrative to the study of language, text or discourse, downplaying the role of media or intermediaries in the story. I propose to define media and intermediaries in terms of a separate reality that plays an important role in the process of constructing the story. I combine cognitive science, especially enactivism, speculative realism and the actor-network theory to build a foundation for a new theory of narratology. New narratology should take into account the narrative role which objects play in the narrative. I exemplify how this theory can be used in practice in my analysis of Bruno Schulz’s Street of Crocodiles.

1 I draw on the critique of transcendentalism presented in recent years by Quentin Meillassoux and Graham Harman. In his object-oriented philosophy, Harman criticizes transcendentalism as a philosophy that undermines and distorts the object. See. G. Harman, The Quadruple Object, London, 2011, p. 11. Meillasoux rejects the transcendentalism underlying correlationism. See: Q. Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, New York, 2010.

2 See: The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition, edited by A. Newen, L. De Bruin, S. Gallagher, Oxford, 2018.

3 S. Krämer, Figuration, Anschauung, Erkenntnis. Grundlinien einer Diagrammatologie, Berlin 2016.

4 M. Martinez, M. Scheffel, ”Narratologia otwarta”, interview conducted and translated by T. Waszak, Litteraria Copernicana 2013, no. 2 (12), p. 130-140.

5 The term “enactivism” refers to a famous publication on embodied and enactive cognition. See: F. J. Varela, E. Thompson, E. Rosch, The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, Cambridge-London 1991. Today, such an approach is developed by many authors, including: D. D. Hutto, E. Myin, Radicalizing Enactivism: Basic Minds without Content, Cambridge, 2013.

6 M. Caracciolo, The Experientiality of Narrative: An Enactivist Approach, Berlin-Boston, 2014.

7 Y. B. Popova, Stories, Meaning, and Experience: Narrativity and Enaction, New York-London, 2015.

8 M. Fludernik, Towards a ‘Natural’ Narratology, London, 1996, p. 12.

9 B. Latour, Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies, Cambridge, 1999.

10 G. Harman, Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy, Ropley, 2012.

11 We should emphasize that the concept of construction used by Latour does not lead to conclusions usually associated with social constructivism. According to the French sociologist, reality is constructed, but not in the human mind, but in a network of actants.

12 B. Schulz, The Street of Crocodiles, translated by Celina Wieniawska, London, 1992.

13 In the present article, I attempt to formulate the theory for the analysis of Schulz’s story. The interpretation based on the theoretical approaches discussed here will be presented in a separate article.

14 See: A. Sandauer, ”Rzeczywistość zdegradowana (rzecz o Brunonie Schulzu)”, [in:] A. Sandauer, Studia o literaturze współczesnej, Warsaw 1985 p. 561-582; W. Panas, Księga blasku: Traktat o kabale w prozie Brunona Schulza, Lublin, 1997.

15 I discuss this question further in: P. Tomczok, ”Ojciec, brat i nauczyciel prac ręcznych”, [in:] Przed i po. Bruno Schulz, edited by J. Olejniczak, Cracow 2018, p. 129–159.

16 The term coined by James J. Gibson is often used in psychology and cognition.

17 On visualization in science from the perspective of the history of media see: S. Krämer, Figuration, Anschauung, Erkenntnis. Grundlinien einer Diagrammatologie, Berlin, 2016; O. Breidbach, Bilder des Wissens. Zur Kulturgeschichte der wissenschaftlichen Wahrnehmung, München, 2005.

18 R. Barthes, “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative”, New Literary History, Vol. 6, No. 2, 1975, p. 237.

19 K. Friedemann, Die Rolle des Erzahlers in der Epik, Leipzig, 1910, p. 34.

20 Daniel Everett writes about the critique of generative linguistics and the treatment of language as an abstract system of rules, demonstrating how language is dependent on culture. See: D. L. Everett, How Language Began: The Story of Humanity’s Greatest Invention, New York, 2017; D.L. Everett, Language: The Cultural Tool, London, 2012.

21 M. Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, Paris, 1969.

22 B. Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, Cambridge, 1991.

23 F.K. Stanzel, Theorie des Erzählens, Göttingen 2008, p. 12.

24 F.K. Stanzel, Theorie …, p. 74.

25 See: D. Mersch, Théorie des médias: Une introduction, Paris, 2018, p. 184.

26 B. Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns. Translated by C. Porter, Cambridge-London, 2018.

27 Herman defined Cognitive Narratology, [in:] The Living Handbook of Narratology, http://www.lhn.uni-hamburg.de/node/38.html, (date of access March 1, 2019).

28 An interesting application of the new cognitive science to research on scientific cognition is the book by Ł. Afeltowicz entitled Modele, artefakty, kolektywy: Praktyka badawcza w pespektywie współczesnych studiów nad nauką [Models, Artifacts, Collectives: Research Practice in the Perspective of Modern Studies on Science] (Toruń 2012).

29 A. Palmer, Social Minds in the Novel, Columbus 2010.

30 Simulation is described in more detail in: B.K. Bergen, Louder Than Words: The New Science of How the Mind Makes Meaning, New York 2012.

31 Y. B. Popova, Stories, Meaning, and Experience…, p. 4.

32 W. Benjamin, ”The Storyteller: reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov”, [in:] The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory 1900-2000, edited by Dorothy Hale, Malden 2006, p. 377.

33 G. Harman, The Quadruple Object.

34 See: R. Barthes, “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative.”

35 This is how Harman describes real objects. See: G. Harman, The Quadruple Object, p. 99. Harman discusses metaphor in more detail in: Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything, London, 2018.

36 The enactivist approach to narrative proposed by Caracciola is actually mentalistic: consciousness operates independently of the body and things, even imagined things.

37 M. Bal, Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. Toronto, 1985.

38 Such a distinction is used by M. Caracciolo, The Experientiality of Narrative…, p. 74.

39 B. Olsen, In Defense of Things: Archeology and the Ontology of Objects. Lanham, 2010.