Gerard Ronge

a b s t r a c t

D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages [Realism without borders] by the French critic and Marxist thinker Roger Garaudy is one of those books that are difficult to discuss. Both the author and the reader of this article may feel anxious about the topic. Therefore, I should start by explaining why I think this book is worthy of critical attention.

Indeed, Garaudy’s book is not an obvious subject of a critical essay, for at least three reasons. For one, it did not stand the test of time. It did not arouse much interest in Poland at the time of its release in 1967 (four years after the French original was published) and as a result it was quickly forgotten. Only Stefan Żółkiewski looked at it with a kind eye (he discussed the French original in the weekly Polityka; the extended version of this essay was later included in his book Zagadnienia stylu [Questions of style]). Respectively, Alina Brodzka devoted an entire chapter to the analysis of Garaudy’s book in her monumental study O kryteriach realizmu w badaniach literackich [On realism in literary studies]. Apart from these two critical texts, D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages has been discussed only sporadically and today it is practically not present in the Polish theoretical and literary discourse.

Secondly, the book is devoid of a coherent theoretical framework that could help systematize the aesthetics exemplified by Picasso, Saint-John Perse and Franz Kafka, to whom Garaudy devotes three critical essays that make up the entire study. While Garaudy analyzes the works of these great artists of the twentieth century in depth, he fails to demonstrate the connections between them, thus failing to prove that the titular “realism without borders” is indeed a valid notion. Naturally, as I shall try to demonstrate, Garaudy formulates some basic theoretical convictions, while other points can be inferred indirectly from his essays. Indeed, some fragments of Garaudy’s essays are “without borders,” but they do not really refer in any way to the notion of realism. Garaudy formulates his judgments without a clearly defined theoretical basis. Only at the beginning of his essay on Picasso does he explain that he expands and radically reformulates the definition of realism in order to clearly distinguish between bourgeois and Marxist realisms. However, he does not reflect on his own methods further on in the book, which is why it is not entirely clear why his criticism should actually be classified as a Marxist critique. As a result, the reader gets the impression that Garaudy defends himself against his own accusations – as if he felt that his approach to art and literature is not always fully Marxist, thus trying to justify it only through the very fact of his self-identification as a Marxist. Indeed, he seems to be aware of this paradox. For example, when he poignantly explains his love for the “bourgeois artist” Saint-John Perse:

The style of this poem is a lifestyle. Why, then, should it not make me, a communist, feel anything else than what his author intended?

It is not important to me that the author, perhaps, turns away from the future, the construction of which gives meaning to my life, […] his eyes look at the rising sun, and we, indeed, we try to make a new day come, the day of fulfillment for the poet and the prophet1

Or when he sees that while Kafka provides an accurate diagnosis of human alienation in an industrial society, he does not formulate a positive program of transformation. Garaudy tries to make amends for the non-revolutionary character of Kafka’s work, as if such amends were necessary:

Similarly to Marx, Kafka was of petty-bourgeois origin. In contrast to Marx, however, Kafka does not not transgress the historical perspective […] of his class. A witness to the October Revolution and the rise of the workers’ movement, he remains a slave to alienation, which he exposes in his works. Alienation does not make him draw revolutionary conclusions, although he manages to turn it into moving art. We should therefore be aware of the petty-bourgeois origin of Kafka, of class his background, […] however, we should not forget that this necessary analysis is neither an explanation nor a valuation.2

While Garaudy makes some very interesting observations, he fails to support them with a sound theoretical grounding. Probably because he addresses the question from the wrong perspective. If it were not for the use of some key words (“revolution,” “bourgeoisie,” “socialism” and the like), the philosopher’s argument would not be recognized as Marxist at all. Indeed, Garaudy as if proclaims “it is Marxism,” but he fails to support his claim. Moreover, the philosopher lacks the courage to identify the weaknesses and limitations of Marxist aesthetics and offer solutions to these problems. Julian Kornhauser and Adam Zagajewski in Świat nie przedstawiony [The unrepresented world] had the courage to engage with Marxism and socialist realism critically (and we should remember that they could have been severely punished for that in communist Poland, while Garaudy only faced the criticism of his colleagues from the French Communist Party), and thus their study constitutes a much more insightful and interesting critique than the one proposed by the French philosopher. Nevertheless, as I shall explain later, D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages can complete the argument presented in Świat nie przedstawiony.

Thirdly, writing about Garaudy is problematic, because he is a disgraced Marxist. In his leftist critic of Israeli imperialism and its cruel policy towards Palestine, Garaudy goes as far as to deny the Holocaust (Garaudy was convicted and fined for Holocaust denial after the publication of his book The Founding Myths of Modern Israel in 1996). This stigma, combined with symptoms of senile detachment from reality he experienced in the old age (believing in conspiracy theories and accusing the US government of arranging the 9/11 attacks), makes it easy to dismiss the unsubstantiated, underdeveloped and unconvincing aesthetic argument presented in D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages. Indeed, no one believed that this aesthetic theory should be remembered.

The fact that D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages has been excluded from the Polish, and global, theoretical discourse is therefore understandable. At the same time, I think that today, a few years after Garaudy’s death, we should reexamine book. I believe that it can be useful for two reasons. Firstly, Garaudy’s book complements the discussion about realism that took place in Polish literary studies in the 1960s and the 1970s, culminating in the publication of the above-mentioned Świat nie przedstawiony by Kornhauser and Zagajewski. Secondly, this discussion informs the contemporary ongoing criticism of littérature engagée.

Janusz Sławiński reconstructed the image of literary life in communist Poland in an essay entitled Rzut oka na ewolucję poezji polskiej w latach 1956-1980 [The evolution of Polish poetry from 1956 to 1980]. Sławiński argues that after 1956 the doctrine of socialist realism was abandoned and dismissed by all Polish artists of that time, i.e. not only by independent poets, who had criticized the doctrine more or less openly, but also by its former apologists and advocates. At the same time, socialist realism was indeed “dismissed,” because no manifestos were issued against the oppressive party program; instead, poets quietly and dispassionately returned to earlier poetics and stylistics, as if simply resuming old projects after a break:

[…] there was a real revolt [in poetry, GR]. What else can we call this universal and definitive break with the poetical monoculture of the Stalinist years? Socialist realism sank into oblivion, abandoned and forgotten by everyone who had praised it and contributed to its development. Nobody really wanted to support it; nobody felt responsible for it. It did not even continue in the form of parody, which is what usually happens with outdated styles in times of artistic breakthroughs. Socialist realism turned out to be so dead that it could not even be turned into a parody.

Such a consistent rebellion rarely takes place. Usually, new trends react to the outdated aesthetics. The violators who reject the previous conventions without remorse, are usually accompanied by reformists, who are satisfied with partial innovations in literature. The latter act as perverse continuators. They pretend to adopt the language of their predecessors so that they can secretly destroy it from the inside. All sorts of imitators, not to mention epigones, also play a role in this process.3

Sławiński is right, but he does not address one important issue, thus somewhat simplifying and misrepresenting the critical debate. Indeed, Sławiński does not make a clear distinction between socialist realism, defined as a set of principles and prohibitions issued by the Polish communist party and enforced by the whole apparatus of political repression (this type of realism known under the name of “socrealism” was indeed “erased” from Polish literary life), and realism, conceived of as a complex theoretical category, on which the aesthetic program of Marxism was based. The latter was indeed defined as the embodiment of modernity and dominated the twentieth-century aesthetics (the simplified overview of this process looks as follows: such an approach was first formulated in the Enlightenment theory of progress; then, it took the form of Hegel’s dialectics; finally, it took the form of historical materialism; afterwards, the end of great narratives was announced, for better or for worse). Of course, Sławiński does not combine these two issues into one, but also does not pay attention to realism in literature after 1956, which no longer functioned in the context of “socrealism.” Indeed, we must remember that socialist realism was directly conditioned by Marxist realism, even though it constitutes a caricature or a distortion of the latter. And when Sławiński argues that socialist realism was “dismissed,” he wrongly suggests that after 1956 there was no critical debate about realism in Poland.

Realism was still a vital issue for the most influential and most renowned literary critics. One of the main advocates of socialist realism in literature, Stefan Żółkiewski, continued his research on realism, using Marxist methodology. He never questioned his leading role in the cultural regime of the Stalinist period. While after 1956 he moved away from socialist realist orthodoxy, searching for a more open formula of realism that could embrace avant-garde and formalistic artistic strategies,4 he still firmly believed in the principles of socialism. Regardless of how we may judge him today, he never acknowledged that he should explain why he played such an important role in the Stalinist cultural regime. Moreover, he did not even find it necessary to abandon the very term “socialist realism.” Instead, he tried to redefine it.

Realism was a central category also for Henryk Markiewicz. He discussed the principles of Marxist methodology in Główne problemach wiedzy o literaturze [The main problems of literary criticism]. His definition of realism, however, does not resemble the “open” conceptualizations formulated by Żółkiewski and Garaudy, which is why I shall not draw on Markiewicz in my discussion of D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages.

The most interesting Polish critical study on realism is Alina Brodzka’s O kryteriach realizmu w badaniach literackich. Apart from Żółkiewski, Brodzka was the only serious critic of Garaudy’s aesthetics. While she acknowledged that Garaudy’s model could be criticized, she still recognized its potential for formulating an “open” definition of realism.

Therefore, we should “supplement” Sławiński’s study with the following observation: although it is true that socialist realism disappeared from Polish poetical practice after 1956, literary critics still actively argued about realism.

The fact that Sławiński did not acknowledge that made him make a strange mistake later on part in his study. He rightly observed that when poetry was freed from the constraints of socialist realism, authors began to publish numerous works in which they used formerly “illegal” conventions and restored poetry to, as Sławiński put it, a “normal” state, i.e. a situation in which various artistic trends compete and engage in a creative dialogue with each other.5 However, Sławiński also pointed out that “normality” had its constraints:

[…] poetry was to distance itself from the social world, in which a special place was assigned for official matters governed by the authoritative discourse of power. The poetical should not compete with the political: neither as a diagnosis nor as a critique/instruction. Nobody asked poetry to pledge itself to ideology – it was out of the question. No one has told poetry what and how to speak; it was expected, however, that poetry should know when it should be silent. Deliberate and theatrical silence was not allowed. Silence that ostentatiously expressed bitterness, helplessness or resignation was not allowed. Silence that openly pointed to the absence of speech was not allowed. Only silence that was unnoticeable and unimportant was allowed.6

I believe that Sławiński made a mistake by not referring to Julian Kornhauser and Adam Zagajewski’s Świat nie przedstawiony. Sławiński concentrated in his analysis on Polish poetry from 1956 to 1980 and Kornhauser and Zagajewski’s book was published in 1974, thus it should have been included in Sławiński’s study. The fact that Sławiński does not mention Kornhauser and Zagajewski’s book is extraordinary, since Kornhauser and Zagajewski were frustrated by the state of Polish poetry, which Sławiński accurately diagnosed. The two young poets wrote their famous manifesto in response to Polish poetry after 1956. Indeed, the abovementioned observations by Sławiński regarding the shape of Polish poetry after 1956 and its relation to the world in general are very similar to the accusations made by Kornhauser against Polish artists who made their debut in the 1950s:

This style was not just a symptom of decline following the cultural restraints imposed by the regime. Some considered it their literary choice. Literature was meant to be “aesthetical,” in opposition to “non-literary” criticism, journalism, politics and everyday life.

The value of this generation did not lie in its independence. Suddenly, they were given a big chance and instead of proclaiming real values, they felt lost. The grotesque and the ridicule did not transgress the border between literature and reality. It was never an aggressive attack. They wanted to suddenly see the gap between literature and reality, oblivious to its destructive nature. […] They lacked a strong, authentic voice. Instead we were given second-rate Norwids, Gałczyńskis, Lieberts, Morsztyns, Kochanowskis, Surrealists and Realists. The cult of form and pastiche was established. The era of Mannerism begun. Psalms, ballads, nocturnes, pastorals and songs were created. Nobody wanted to open their eyes and go to university.7

While Sławiński’s observations on the thirty years of Polish poetry contribute to the history of literature, they do not offer a new perspective. Indeed, Kornhauser and Zagajewski, who write as “direct witnesses” to the processes discussed by Sławiński, give more insight into the mechanics of literary trends in Poland.

Kornhauser and Zagajewski call for literature (poetry and “medium” novels) that could offer an honest and insightful description of contemporary reality. Instead, Polish literature was either an escapist (abandoning reality for aesthetics; focusing on the personal or the historical) or a parodic (mocking) rendition of reality.8 Kornhauser and Zagajewski argue that literature must capture the “spirit” of the times, looking beneath the surface of the banal and the everyday to expose the hidden essence of reality:

Perhaps this world of delegations, presidential tables covered with red cloth, Labour Day parades, conferences, people going to work early in the morning is just as deep as the world that exists only in dreams. Perhaps this world, with all its problems and hidden truths, joys and sorrows, would turn out to be a world worthy of literature.9

However, the above quote also exemplifies the main problem of Świat nie przedstawiony, of which Kornhauser and Zagajewski were probably not fully aware. Kornhauser and Zagajewski approach reality in essentialist (or, to refer to the Marxist categories that both poets knew very well, in materialistic) terms. The authors never question such an approach, failing to analyse it critically.

It seems that this why Lidia Burska criticizes Świat nie przedstawiony in Awangarda i inne złudzenia [The avant-garde and other illusions]. Burska examines the so-called Polish generation of 1968 from a contemporary perspective.

Reducing the complicated argument made by Kornhauser and Zagajewski to a single sentence, Burska accuses the poets of restoring socialist realism and dressing it up with new words. According to Burska, Kornhauser and Zagajewski reproduce in their book the great narrative of historical materialism, defining each epoch as a necessary stage in the continuous march of humanity towards progress (as we remember, according to Marxism, it should culminate in the utopian “true” socialism/communism). Such a narration made it impossible to see a given epoch as a potential breakthrough or, more importantly, as a force that could annihilate the entire logic of “progress.” Kornhauser and Zagajewski seem to believe that behind the façade of reality there exists some essential objective truth. Moreover, this truth is consistent with and relevant to the Marxist project. As a result, as Burska argues, the postulate of realism became, a legitimation of the communist regime in Poland.10

Burska argues that Kornhauser and Zagajewski were very naïve in thinking that Marxism could be reclaimed and restored as a utopian ideology. Indeed, both poets believed that it was possible and saw it as an act of rebellion against the communist party, which had made a mockery of Marxism. However, I think that she judges both poets too harshly. While Burska is perfectly aware that she employs postmodernist tools (i.e. the notion of great narratives) anachronically to discuss a text from 1974 (she claims that she reads Świat nie przedstawiony “avant la lettre”),11 she forgets that at the time the perspective of historical materialism was the only perspective these young poets knew. In Kornhauser and Zagajewski’s defence we could say that “no read Lyotard” in communist Poland. On the other hand, guided by her critique of Marxism, Burska ignores the fact that both poets were aware of the limitations of the Marxist project in its contemporary form. What is more, they tried to solve the diagnosed problems, thus providing an alternative vision of Marxism or, if the reader who reads the study avant la lettre acknowledges that, transgressing Marxism altogether.

Kornhauser and Zagajewski knew that the new realism advocated by them could not resemble bourgeois realism. Moreover, they understood that a new historical reality demands new storytelling formulas. The essential truth, which was to be discovered with the help of realistic literature, was conceived of not in terms of a static “being,” but as processual “becoming.” As such, both poets were concerned with a different form of realism that could not be described as socialist.

It is clearly demonstrated in one of the essays found in Świat nie przedstawiony, namely Kornahauser’s Różewicz: odpowiedzialność czy nudna przygoda? [Różewicz: Responsibility or a boring adventure?]. The works of Różewicz are seen as positive reference points for the study of realism. Kornhauser discusses the works of Różewicz, pointing to their inherent aporias and internal contradictions. He also reconstructs Różewicz’s poetical beliefs, arguing that Różewicz, paradoxically, both doubted that anyone could write poetry after the Second World War and wished to formulate a new poetical manifesto. However, this new poetry, and this point is important in the context of the present article, must reject all its earlier forms, because they had been invalidated by the Second World War. According to Kornhauser, Różewicz’s poetry is full of ambiguities, hesitations, doubts and contradictions. And yet it seems that Kornahuser sees this poetry as “realistic,” because it is “modern:”

The poet suffers defeat. He experiences overwhelming helplessness, hatred, powerlessness and rage. His faith turns into hypocrisy, but it does not silence the truth, which is at the same time the truth of all society. For Różewicz, poetry is not a question of aesthetics. The death of poetry, which he proclaimed, was first of all the death of courage and social individualism. The poet’s internal struggle for the right to poetry and a common language, which he could share with the public, is also a fight for a free voice that vouches freedom. It is not true that Różewicz was a nihilist and that his poems were void; it is not true that he is a boring moralist. His poems do not suggest or change. His poetry reflects the banality and dullness of our civilization.12

I discuss Świat nieprzedstawiony in so much detail, because Roger Garaudy in D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages tried to “deal with” works that were not “standard” Marxist works in a similar manner. Kornhauser and Zagajewski never referred to the then contemporary book of the French philosopher. And, as I shall argue, Garaudy provided answers to questions, which the Polish poets also tried to answer.

Garaudy argued that the nineteenth-century “commonsense” notions of realism based on resemblance distort, and certainly do not represent, reality. In the first essay included in the collection, Garaudy discusses the art of Picasso, arguing that the deformations of bourgeois realism are first and foremost the result of the artificial division between what the artist empirically knows about a given object and what he sees at a particular moment (traditional realism supposedly represents the latter). The critic observes that bourgeois realism imposed an artificial perspective, which stood in contrast to the natural way of perceiving the world by man. Indeed, as Garaudy points out, man perceives reality by using his senses, knowledge and imagination:

Unlike a professional measurer, I do not ask whether Notre Dame can be seen from this or that bridge. In my memory, it is embedded in the Parisian landscape, even if I do not locate it correctly on the map. When I visualize in my mind the face of a woman or a friend, I see it simultaneously from the side, en face and in three-quarters. I can also evoke the vision of the person and its presence, even if such a synthesis cannot be translated into anthropometric measurements.13

Consequently, painting plays an analytic function. It no longer imitates the superficial appearances, but reflects on how man moves around in the world, discovers it and understands it. If we define realism in such terms, it becomes clear why Les Demoiselles d’Avignon may be considered a more realistic painting than an academic nude. Such a new approach would be impossible in both traditional bourgeois realism and socialist realism, as the latter was constrained by the outdated notions of bourgeois realism and was not even aware of this fact.

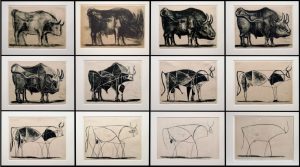

Moreover, such an understanding of realism helps man deepen his knowledge of the world. It allows the viewer to perceive the unseen aspects of objects and discover their essences, hidden underneath superficial appearances. Realism also allows man to understand, and thus change, the world. By defining the aims of art as a transition from appearances to essence, and then from essence to change, Garaudy is able to combine his vision of realism without borders with Marxism. That is why Garaudy refers to The Bull series (1946) by Picasso to exemplify to what painting should aspire in general. Picasso reversed the starting point and the ending point. He began with a stereotypical model, “searching for dynamic lines and constructional outlines,”14 which for previous painters were only a preliminary sketch that should be erased after the work was finished. For Picasso, this hidden outline was the essence of representation:

P. Picasso, “The Bull” 1946. Photograph from the exhibition at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vahemart/31475770070 [date of access: 2 Jan 2019].

For Garaudy, searching for the essence defines realism at its core. Indeed, the French philosopher refrains from defining realism in terms of aesthetics, searching instead for images, aspirations and processes that capture the spirit of an era in art and literature.

Unfortunately, Garaudy does not specify what this spirit of the epoch is supposed to be; he only observes that it should correspond to the Marxist understanding of progress and change. Nevertheless, the critic does not believe that art should provide a ready-made vision of the future or directly formulate political or social postulates. According to Garaudy, the subversive potential of art and literature may be hidden in the critique of reality they offer:

It would be desirable for a writer or an artist to have a clear vision of the future, thereby through their works committing to fight. But if we were to limit ourselves to this perspective, we would have to address the problem posed by Baudelaire, who asks “Whether the so-called virtuous writers are tackling successfully the problem of inspiring love and respect for virtue?” Art is moral when instead of offering ready-made solutions, it raises awareness.

Marxism does not underestimate the unique properties of art.15

Such assumptions allowed Garaudy to appreciate Saint-John Perse. While Garaudy believed that Perse was guided by principles that were foreign to him, he still admired the poet for showing the “greatness of man” and “a promising future”16 in his poetry.

The essay on Saint-John Perse is undoubtedly the weakest part of Garaudy’s book, because the critic does not present in it any clear theoretical propositions. However, Garaudy manages to develop his argument on realism (first outlined, as we remember, in the first essay devoted to the works of Picasso), which he further advances in the final essay on Kafka.

It seems that Garaudy respected Kafka in a manner that was similar to that in which Kornhauser respected Różewicz. In his novels and short stories, Kafka examined the alienation of the individual in industrial society, with its merciless and bureaucratic mechanisms. For Garaudy, such a look upon the world is essentially a form of Marxist social critique, even though the writer employed a completely different language and theoretical framework:

Kafka was a witness, a victim and a judge of a social reality that is as unimaginable as magical and mythical world of primitive peoples. The difference is that in Kafka’s works man feels alienated, because he feels helpless against the social forces which are increasingly incomprehensible and hostile and not because he is fighting against the forces of nature. People and their works, dreams and values may be annihilated at any time. Anxiety and constant fear define everyday life in the world of alienation. And Kafka makes us aware of that. No translator is needed: Kafka describes reality as it is, without additions. He describes reality as it is, that is, as a well-oiled mechanism, but also as an inherent threat – violent and oppressive. He also demonstrates that such a reality inspires stupor, irony and rebellion in the heads and hearts of people. Kafka, through description only, calls for a different world; nevertheless, he does not see the force through which the transition from one reality to another takes place.17

At this point, we should refer to Garaudy’s another aesthetic postulate. He strongly opposes (especially in the case of Kafka) separating form from content. Indeed, he believes that artistic creation is similar to myth-making. The realist writer is not to describe reality in detail, but to discover its hidden aspects by creating covert symbols and references. In this way, art not only passively reflects reality, but it also actively creates a new world. However, such a reading is not be possible, if we do not respect the autonomy and unique character of a given work of art:

The Commandant in ”In the Penal Colony,” the Emperor in “The Great Wall of China,” the Judges in The Trial and the Officials in The Castle are not simply allegories of Father, Capital or Kierkegaard’s God. If that was the case, Kafka would have become a psychoanalyst, an economist or a theologian. Kafka is not a philosopher, but a poet, i.e. he does not try to persuade or prove his thesis, but he wants to convey to us, to visualize, the world and how to live in it without confusion.

Like all great artists, Kafka sees and constructs the world from images and symbols. He sees and makes us aware of the connections between things, combining experience, dreams, fiction and magic. While different, sometimes conflicting, meanings animate his works, he manages to present the reader with everyday problems, dreams, philosophical concepts and religious beliefs. Indeed, Kafka expresses the desire to transgress the limits of the world.18

As such, we can clearly see that Garaudy seems to follow in the footsteps of the American School of New Criticism (Cleanth Brooks’s thesis about the “heresy of paraphrase” in particular19), which, paradoxically, could not be more foreign to him. It is therefore not surprising that Stefan Żółkiewski and Alina Brodzka both criticize Garaudy for that. Indeed, Żółkiewski and Brodzka both agree that the artist should reveal the marks of the “objective” structure of the social world and not create worlds that are not translatable into other languages, because such an approach is useless from the Marxist perspective.20

It seems that Żółkiewski and Brodzka rightly criticize Garaudy – according to Marxist principles, D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages is an inconsistent and incoherent book. However, the same reasons for which this book has been criticized by Marxist critics may today make it relevant for our discussion of realism in literature and literary criticism.

In the early 2000s, Polish critics and artists entered into a heated discussion about littérature engagée. The debate was a reaction to the dominating poetics of the 1990s – it was primarily established by the Polish avant-garde literary magazine bruLion and focused on such notions as privacy, aesthetic formalism, artistic autonomy, nostalgia, spirituality, identity and, above all, apoliticality. Naturally, in response to such a apolitical aesthetics, some artists and critics argued that art should comment on society and politics, constituting the driving force of positive changes. In other words, art should engage with (by all means political) reality.

I do not think that I need to summarize the entire critical discussion, since Alina Świeściak comprehensively reviews it in her essay “Fikcja awangardy?” [The Fiction of the Avant-Garde?] that was published in Teksty Drugie in 2015.21 Naturally, this discussion did not come to an end in 2015. However, it would be fair to say that since 2015 it no longer concerns primarily critical and theoretical discourse. Instead, it refers to poetical practices per se, as exemplified by, inter alia the anthology Zebrało się śliny [Some saliva] edited by Paweł Kaczmarski and Marta Koronkiewicz, the poetical series edited by Maja Staśko and published by Ha!art, or the Poznań Foundation for Academic Culture. What I wish to emphasize is that the notion of littérature engagée may be considered theoretically relevant only if it addresses the twentieth-century crisis of literary representation.

While the authors of the most popular manifestos of littérature engagée formulate valuable propositions and accurately diagnose the social and political causes behind the failed attempts to develop engaged art in Poland, they fail to specify what mechanisms would allow art to make a difference in a non-artistic reality. Neither do they explain how we can move away from the linguistic turn, which has kept the linguistic reality and the reality of the real world separate for many years. Indeed, the question of realism is never posed.

Before we repeat after Artur Żmijewski that artists are “genius idiots,”22 who are able to make accurate observations, but do not understand the mechanisms which govern social reality, we should first establish the philosophical foundations that would help determine the objective existence of such mechanisms and then offer aesthetic tools that can be used to discover them.

In view of today’s knowledge of the mechanisms of cultural production, we cannot dismiss the problem of misguided interpretation by repeating after Żmijewski that “art literally ‘shows’ what it knows.”23 We cannot defend such a statement, because we would have to return to and restore “essentialist” literature criticism and develop new analytical tools with the help of which we could validate “objective” and invalidate erroneous interpretations.

While we could argue that Igor Stokfiszewski is right when he argues that (among others) Dorota Masłowska and Michał Witkowski “do no longer refer to a vision of postmodernism in literature which distances itself from social issues, writing works with a clear social edge,”24 we would have to examine why and how both writers employ (on such a massive scale) post-structuralist principles of writing, based on quotations, pastiche and parody, and how they use them for their own (political) purposes. If we want to convincingly argue that Snow White and Russian Red or Lubiewo can be classified as littérature engagée, since both works represent excluded social groups (respectively, the youth living in communist blocks of flats and the gay community), we have to demonstrate how these books represent reality in literature in general. Indeed, we can clearly see that neither Snow White and Russian Red nor Lubiewo are “traditionally” realistic.

Indeed, I would argue that the manifestos of littérature engagée (apart from the abovementioned texts by Żmijewski and Stokfiszewski, it is worth mentioning the edited volume entitled Manifest Nooawangardy [The manifesto of Noo-avant-garde) rarely explain how their (theoretical) postulates should be realized. If art and literature are to have political and social significance, we need to answer two fundamental questions, which in my opinion, pertain to realism as a category. Firstly, what “aesthetic and technical” tools can help bridge the gap between the artistic and non-artistic realities that exists since the Linguistic Turn? Secondly, how can we protect these tools from being appropriated by the hostile reactionary and conservative forces (whose political position is clearly defined)? In other words, how can we justify that there exists an objective political and social reality that can only be accurately described in leftist and emancipatory terms?

Naturally, D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages does not offer ready-made answers to the above questions, but it nevertheless presents us with two very interesting perspectives. Firstly, it illustrates and reminds us that any discussion of littérature engagée must begin with realism, more than on any other literary and critical category. Secondly, D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages demonstrates that we can talk about realism on many levels, because it is a dynamic and broad critical category that should no longer be conceived of in terms of outdated aesthetic concepts. Garaudy’s more or less successful interpretations of Picasso’s paintings or Kafka’s stories demonstrate that true works of art in one way or another engage with social and political issues (which is not to say that they exemplify Marxist historiosophy), even if, as Louis Aragon observes in the preface to D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages, the book consciously distances itself from realism.25

translated by Małgorzata Olsza

The article discusses the largely forgotten concept of realism developed by the French Marxist philosopher Roger Garaudy in his book D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages [Realism without borders].

In the first part of the article, I discuss the context in which the book was discussed when it was first published in Poland in 1967. I compare and contrast Garaudy’s observations with Polish critics, who, at the time, were also actively and passionately discussing the question of realism. Specifically, I refer to Julian Kornhauser and Adam Zagajewski’s Świat nie przedstawiony [The unrepresented world] and Janusz Sławiński’s Rzut oka na ewolucję poezji polskiej w latach 1956-1980 [The evolution of Polish poetry from 1956 to 1980].

In the second part of the article, I analyse the selected fragments from Garaudy’s book, demonstrating that D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages may inform contemporary literary criticism and theory. I try to answer the question whether and how the tools proposed by the French thinker may be useful in describing contemporary literary phenomena and how his ideas can be used to formulate a new, not necessarily Marxist, concept of realism.

1 R. Garaudy, D’un Réalisme Sans Rivages, Paris 1966, p. 142.

2 Ibid., p. 209.

3 J. Sławiński, ”Rzut oka na ewolucję poezji polskiej w latach 1956-1980”, [in:] J. Sławiński, Teksty i teksty, Warsaw 1990, p. 97-98.

4 See further: G. Wołowiec, ”O ‘nowoczesny realizm socjalistyczny:’ Stefana Żółkiewskiego poglądy na literaturę społecznie zaangażowaną,” Nauka 2006, no. 3.

5 J. Sławiński, op. cit., p. 104-107.

6 Ibid., p. 111.

7 J. Kornhauser, A. Zagajewski, Świat nie przedstawiony, Cracow 1974, p. 74-75.

8 Ibid., p. 38-39.

9 Ibid., p. 39.

10 L. Burska, Awangarda i inne złudzenia. O pokoleniu ’68 w Polsce, Gdańsk 2012, p. 258-259.

11 Ibid., p. 258.

12 J. Kornhauser, A. Zagajewski, op. cit., p. 58.

13 R. Garaudy, op. cit., p. 46.

14 Ibid., p.49.

15 Ibid., p. 199.

16 Ibid., p. 138.

17 Ibid., p. 169.

18 Ibid., p. 201.

19 See further: C. Brooks, “The Heresy of Paraphrase”, [in:] C. Brooks, The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry, Fort Washington 1956, p. 192-214.

20 See further: A. Brodzka, O kryteriach realizmu w badaniach literackich, Warsaw 1966, p. 225-231, 249-252.

21 A. Świeciak, ”Fikcja awangardy?”, Teksty Drugie 2015, no. 6, p. 47-69.

22 A. Żmijewski, Stosowane sztuki społeczne, http://krytykapolityczna.pl/kultura/sztuki-wizualne/stosowane-sztuki-spoleczne/ [date of access: 10 Jan 2019].

23 Ibid.

24 I. Stokfiszewski, Zwrot polityczny, Warsaw 2009, p. 30.

25 See further: L. Aragon, “Préface”, [in:] R. Garaudy, op. cit., p. 12.