Joanna Grądziel-Wójcik

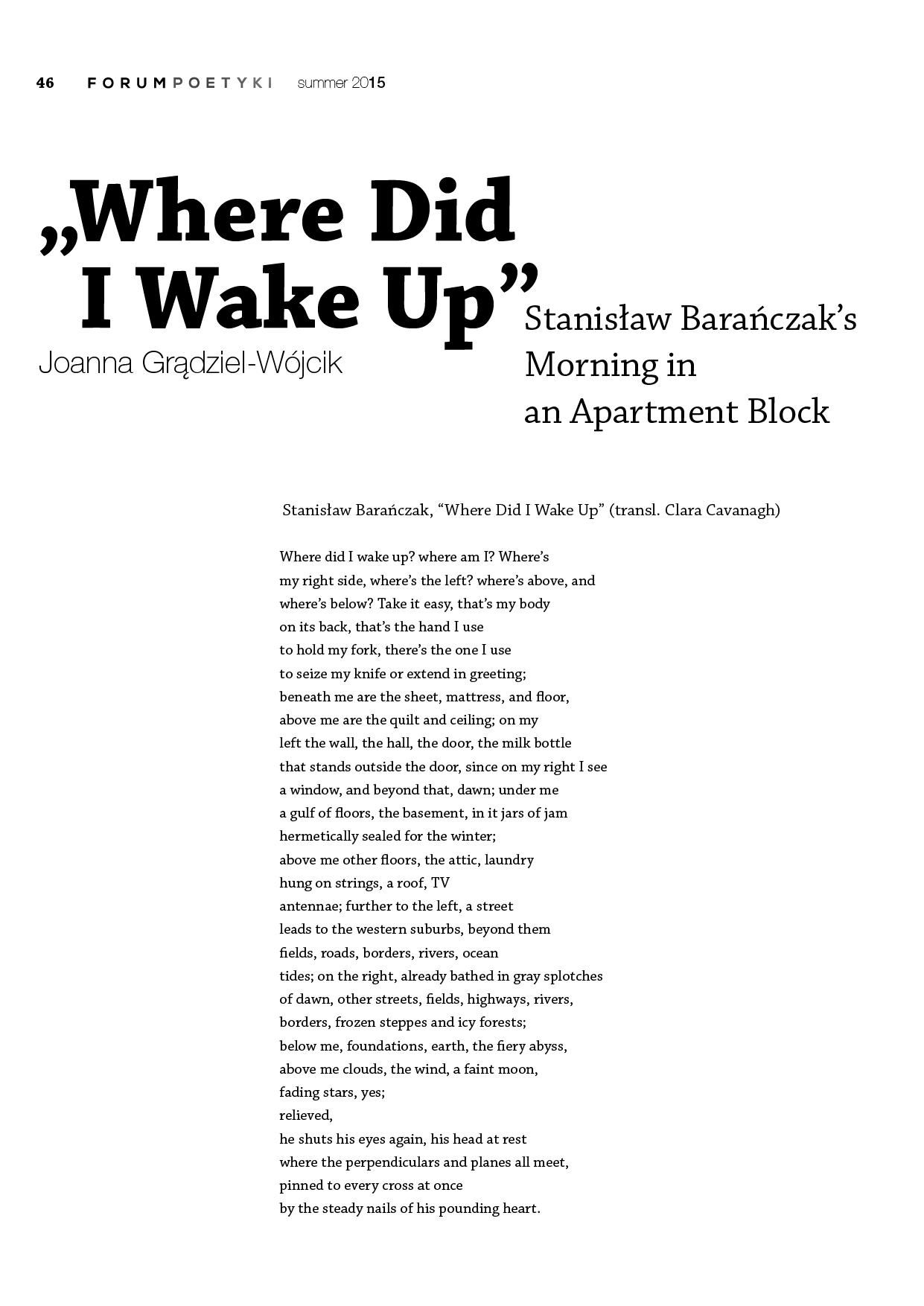

Stanisław Barańczak, “Where Did I Wake Up” (transl. Clara Cavanagh)

Where did I wake up? where am I? Where’s

my right side, where’s the left? where’s above, and

where’s below? Take it easy, that’s my body

on its back, that’s the hand I use

to hold my fork, there’s the one I use

to seize my knife or extend in greeting;

beneath me are the sheet, mattress, and floor,

above me are the quilt and ceiling; on my

left the wall, the hall, the door, the milk bottle

that stands outside the door, since on my right I see

a window, and beyond that, dawn; under me

a gulf of floors, the basement, in it jars of jam

hermetically sealed for the winter;

above me other floors, the attic, laundry

hung on strings, a roof, TV

antennae; further to the left, a street

leads to the western suburbs, beyond them

fields, roads, borders, rivers, ocean

tides; on the right, already bathed in gray splotches

of dawn, other streets, fields, highways, rivers,

borders, frozen steppes and icy forests;

below me, foundations, earth, the fiery abyss,

above me clouds, the wind, a faint moon,

fading stars, yes;

relieved,

he shuts his eyes again, his head at rest

where the perpendiculars and planes all meet,

pinned to every cross at once

by the steady nails of his pounding heart.

It makes sense to begin with what the poem conveys in the most literal sense, with the “unique truth of the concrete” at the level of the world presented in the poem, the truth that Stanisław Barańczak prized so highly. The psychosomatic and perceptual situation of the poem’s subject (its persona) is made possible by the delineation of the temporal and spatial relations in which he found himself: the text locates the “I” in the concrete “here and now,” determining his way of expressing himself and offering the reader an interpretative angle– there is nothing in the poem that the speaker would not have experienced with his five senses,1)See A. Nasiłowska, Persona liryczna (The Lyrical Persona), Warszawa 2000, p. 49. and his complex monologue, developing in statu nascendi, constitutes an answer to the question in the title, “Where am I?” the driving force of the lines that follow. The answer appears simple enough: the subject finds himself in his apartment block, in his apartment, in his bed; his awakening is completely physical, conveying the everyday experience of spatial disorientation that we usually feel in a new, unfamiliar place– as we open our eyes, we’re not quite grounded or able to define where we are. The poetic persona’s depth perception fails him, and his sense of proproception, linked to the awareness of the body’s place in space, is impaired, which is why the first two lines are full of short questions, five in a row, as if in a panic, nervously repeating the interrogative pronoun. The text thus begins with a specific “system of abbreviation” in which phrases are shortened to make their meanings more precise (the opposite of Tadeusz Peiper’s concept of a system of expansion2)On Barańczak’s system of expansion, see D. Pawelec, Poezja Stanisława Barańczaka. Reguły i konteksty (The Poetry of StanisławBarańczak. Rules and Contexts), Katowice 1992, pp. 60-62. I have engaged in a broader discussion of connections between Barańczak’s early poetry and TadeuszPeiper’s concept in Dziennik poranny, which is an offshoot and a critical continuation of the thought of the leaders of the early avant-garde, in “‘Zmiażdżona epopeja’. Dziennik poranny Stanisława Barańczaka a twórczość Tadeusza Peipera” (The “Crushed Epic.” Stanisław Barańczak’s Dziennik poranny and the Work of Tadeusz Peiper) in: J. Grądziel-Wójcik, Przestrzeń porównań. Szkice o polskiej poezji współczesnej (Space of Comparisons. Sketches on Contemporary Polish Poetry), Poznań 2010, pp. 114-130.): “Where did I wake up? where am I? Where’s” and the cognitive reductionism implied in those words continues throughout the poem, despite the fact that it revolves in ever-widening circles in space. The persona attempts to determine his position and his relation to his external environment – “Where’s / my right side, where’s the left? where’s above, and / where’s below?” – and this effort takes up almost the entire text, while the poem clarifies the reason for that disorientation – the man’s problems with proprioception are linked to a specific architectural context that influences his way of understanding the world in language.3)See M. Rembowska-Płuciennik, “Propriocepcja” (Proprioception) in: Sensualność w kulturze polskiej (Sensuality in Polish Culture), http://sensualnosc.ibl.waw.pl/pl/articles/propriocepcja-394/ [accessed: 26.01.2015]. The persona’s sense of being lost and the incoherence of his body-image are reflected in the disintegration of his syntax.

Our ideas about the world begin with our bodies. In attempting to explore an aspect of the world, the subject finds a reference point in his own body, in a sense newly discovering and labeling it. The situation is extremely Gombrowiczesque: the poem’s “I,” like Józio in Ferdydurke, wakes up in his own room with a feeling of strangeness and tries to rebuild his identity starting from bodily: “that’s the hand I use / to hold my fork, there’s the one I use / to seize my knife or extend in greeting.” To wake up means to be conscious, and that becomes possible through the persona’s re-corporealization(location is dependent on embodiment) and his reinstatement or imposition of order on his world: “The presence of the body here coordinates the experience of space, defines the axes of perception and measures existential distances. Movement and time become basic components of such an experience, and inseparable from space.”4)E. Rewers, Post-polis. Wstęp do filozofii ponowoczesnego miasta (Post-polis. Introduction to the Philosophy of the Postmodern City), Kraków 2005, pp. 67-68. For the subject of the poem, the question about his location thereby becomes simultaneously existential, metaphysical, and concerned with identity, and his corporeality, fragmented and inscribed in space (arms open wide, eyes shut, heart beating) begins the process of encoding meanings. The strenuous expression of his long-winded answer thus signifies a resistance to physical and psychic disintegration, and can be understood as a process of self-awareness taking place within the subject, in which the chaos of existence and feebleness of the body are overcome. The poem then represents an effort to create cohesion within the body, the one reference point and sure source of an answer, by which the world can be made palpable and real.

The situation comes under control in the third line, where the persona clearly feels relieved: “Take it easy, that’s my body.” This passage shows Barańczak’s poetry, typically difficult to read out loud (because of the strong flow of enjambent and the phonetic complexity) use the diction, intonation, and emotional dramatization of spoken speech: this line demonstrates the poetic mimesis of language, insisting that we reconstruct the pragmatic situation of the utterance, which here functions as action – a calming gesture, as the speaker subdues his emotions and concentrates. At the same time, significantly, in this line the subject begins to signal his distance from his own body: the persona not only speaks from the perspective of soma (speaking as the body) but also looks at it from the outside (speaking about the body), treating it as an object of observation. Only when he becomes aware of its/his presence does he begin to place other, increasingly remote objects in space. The next segment of the poem, beginning in the third verse (in the original, the transition is marked by a colon), begins a phase of identifying the space surrounding the persona, generating questions about the multi-dimensionality and complexity of the human condition, deriving from its corporeality, and about the relationship between matter and metaphysics, between the body and consciousness.

In noting that third line is semantically divided into panic and reassurance, we should also observe the structure of the text in terms of versification. Jerzy Kandziorahas written about “the irregular contour of a stichic poem” and the “baggy space of the work.”5)J. Kandziora, Ocalony w gmachu wiersza. O poezji Stanisława Barańczaka (Saved in the Edifice of the Poem. On the Poetry of Stanisław Barańczak), Warszawa 2007, p. 105. Here, however, it seems that the text’s structure has been carefully thought out, and the spatial opposition and expanding list are part of that structure, serving the poem’s intersecting lines of division. The “perpendiculars and planes” crossing in the text also include the irreconcilably divided claims of versification and syntax, typical in Barańczak’s poems; here, his line endings are moderately harmonious with semantics. The text is divided into three parts: the syntactic structure of the first two lines (and the beginning of the third) emphasizes the persona’s nervous agitation, as we have seen; next, the body is localized in space, expanding fragmentarily, evoked by phrases divided by semicolons that form a single sentence, up to the final semicolon (in the original, a colon) in line 23. That place marks a second semantic turning point, when after the long descriptive section, the subject becomes conscious of his condition: “yes; relieved…”.Here, the poem is divided by a caesura and a fundamental shift takes place, from first-person to third-person narration. The poem’s stichic nature is based on a poetics of speaking “in one breath”6)Here, we are of course dealing with Barańczak’s signature poetics of the poem, heralded by the title of the poem “In One Breath,” with which he opened the eponymous collection, first published in December 1970, and reprinted two years later in Dziennik poranny (Morning Diary).The poem consist of one long, unfinished sentence, broken up into lines of irregular length, structured with a system of expansion, spoken in one breath and ordered only by punctuation, placing commas in the middle of lines; enjambment here works against syntax, rendering the words left in the clausula ambiguous through the tension generated between line intonation and sentence intonation. See Grądziel-Wójcik, Przestrzeń porównań (Space of Comparisons), pp. 121-123. the articulation of questions that resemble an inner monologue slows down when the monologue changes into one long, scrupulously punctuated sentence. At the same time, the poem is not as challenging to recite as, for example, “In One Breath”; the asyntactic flow, typical for Barańczak, is neutralized or softened here by the flow of the list intersecting with it, and there are relatively few strong enjambments. In the original, half of the 28 lines are 13 syllables long, with a caesura after the seventh syllable and a fixed paroxytone accent in the clausula and before the caesura.It occurs interlaced with 11-syllable lines with an equally classical arrangement (5 + 6), appearing nine times, observing accentual regularity in the caesura and the clausula. The remaining 5 lines consist of two 12-syllable lines (lines 2 and 4), one 10-syllable line (line 1), and two 9-syllable lines (lines 11 and 15). The greatest syllabic irregularity occurs in the first four lines (10-12-13-12), but when the subject recognizes his situation and his persona becomes stabilized in space, those more recognizable syllabic formats begin interweaving, with only two lines shortened to 9 syllables. Lines of 11 or 13 syllables are perfectly suited to long, complexly structured sentences with a tendency toward prosaicism; they allow narrative expansiveness and provide a dynamic of space without letting the verse become syllabotonic, i.e., become rhythmized, which could have the effect of exposing its metaphysical subtext too nakedly.7)On the importance of rhythm in Barańczak’s poetry in relation to his metaphysical worldview, see Joanna Dembińska-Pawelec, “‘Poezja jest sztuką rytmu’. O świadomości rytmu w poezji polskiej dwudziestego wieku (Miłosz – Rymkiewicz – Barańczak)” (“Poetry is the art of rhythm.”On the Consciousness of Rhythm in Polish Twentieth-Century Poetry [Miłosz – Rymkiewicz -Barańczak]), Katowice 2010. The subject’s monologue thus becomes suspended in the irregular variation of the phrasing, at times becoming regular for more sustained lengths: six lines in a row, from 17 to 22, describing portions of the landscape to the left and right of the speaker, are regular 13-syllable lines. We are not fully conscious of the meter, because the poet effectively camouflages it, moving syntactic divisions inside lines and thereby weakening the clausulas. At the same time, there is a specific kind of “battle with rhythm” here, in a sense analogous to the one described by Barańczak in his interpretation of Miłosz’s “Świty” (Dawns)8)S. Barańczak, “Tunel i lustro. Czesław Miłosz: Świty” (Tunnel and mirror. Czesław Miłosz’s „Świty” in Barańczak: Pomyślane przepaście. Osiem interpretacji (Thought Abysses. Eight Interpretations), afterword by I. Opacki, ed. J. Tambor and R. Cudak, Katowice 1995, pp. 9-21.: the flow, noticeably mellow when the poem is read aloud, of the 11- and 13-syllable lines, overlaps with the interrupted syntactic progression, and the renewed syntactic flow counteracts their measured smoothness. A total of seven semicolons break up the sentence, shredding it into fragments, each of which begins with a glance at a different side of the persona’s world, distinctly marked by unequal distribution: “beneath me” and “on my left” appear earlier than “above me” and “on my right.” The apparent bagginess of the poem is thus revealed to be illusory, and the stichic outline clearly thought out and logical: it organizes the content of the poem. While Polish poetry’s two dominant and most recognizable forms intersect in the poem, the syllabic meter is also defied by a small number of irregularities.

Let us take another look at the initial semantic turn (after the first colon), where the persona manages to define the position of his body: “to jest mojeciało, / leżącenawznak” (that’s my body / on its back). The persona sees the world from a horizontal, inactive position, looking on from his bed, motionless as if crucified; and indeed, in Polish “na wznak” means “on one’s back” but also includes the meaning “w znak,” “in a sign,” and the persona in effect becomes a sign with his arms spread out left and right– the sign of the cross. This man, the poem’s subject, finds himself “where the perpendiculars and planes all meet,” and his body becomes the center of the universe, an anthropocentric reference point around which the landscape described gradually in the lines that follow expands. Before the sacral references and metaphysical contexts of the poem, its use of Passion imagery and, in the original, the polysemy of the verb “krzyżować się” (to cross oneself, or to intersect),9)Krzysztof Kłosiński deals with this in his interpretation; see Kłosiński, “Ponad podziałami” (Beyond Divisions), in: ”Obchodzę urodziny z daleka…”. Szkice o Stanisławie Barańczaku (“I’m Celebrating My Birthday From Far Away…”. Sketches on Stanisław Barańczak), ed. J. Dembińska-Pawelec, D. Pawelec, Katowice 2007., pp. 24-25. become apparent, however, its conditioning point of departure and poetically constructed “speaking space” features the scenery of an ordinary Polish apartment block of the 1970s.

The text is architecturally organized around spatial terms of definition, “stuffed with words and expressions connected with space and movement in space,”10)Barańczak, “Wzlot w przepaść. Julian Przyboś: Notre-Dame” (Ascent into the Abyss. Julian Przyboś’s “Notre-Dame”) in Barańczak: Pomyślane przepaście, p. 31. divided by oppositions between right and left, high and low, leading the reader “to search for the key to the poem’s overall meaning in its treatment of space,” to quote what Barańczak wrote about Przyboś’s poem “Notre-Dame.” If we adopt this interpretative strategy from Barańczak, who in that poem saw the cognitive transformation of the persona’s record of his experiences and impressions inside a cathedral, then the apartment block in Barańczak’s poem, like the cathedral in Przyboś’s poem, ought to be understood in terms of the relationship between the person and the apartment block: the space of the cathedral or apartment block is both experienced corporeally and exerts influence on the interior of the subject interacting with it. Let us also attempt to reconstruct the lyrical situation, passing Barańczak’s own text “through a sieve that retains precisely such spatial-kinetic units of meaning, words and expressions naming or defining location, movement, direction, position with regard to something, size, and so on, whether of the observer or of any of the objects of description.” In the poem, these elements have been selected to be arranged in contrasting pairs (each of which is heavily freighted with cultural symbolism): left–right, up–down, inside–outside, open–closed, motion–immobility.

The persona’s process of situating himself begins at the horizontal plane: on the left side we have a fork, on the right a knife; “on my left” his gaze reaches through the wall to the hall to the door and the milk bottle; on his right, he sees only the window and the gray dawn. Next, the speaker analyses the vertical axis: “beneath me” are the sheet, mattress, floor,[above him] the quilt and ceiling, and further down beneath the floor–more floors, the basement and the jars of compote (in Cavanagh’s translation, changed to “jam”); above the ceiling– other floors, the attic, strings with laundry, the roof and TV antennae. Here we should pause for a moment, before the persona’s gaze wanders beyond the concrete walls: the poem conveys the architectonic realia of an apartment in a multi-storey block, filled with typical hardware and props, and selects those elements that indicate domesticity and practical everyday activities: cooking, storage, laundry, and watching (TV, the propagandistic window on the world). This poem from Dziennik poranny (Morning Diary) is one of many texts by Barańczak in which the scenery consists of a residential building from the PRL (Communist) era, a challenge to both the aesthetic and the humanistic aspects of architecture. The theme of the experience of living in an apartment block surfaces discreetly in that book, develops further in Sztuczne oddychanie (Artificial Respiration) and returns with increased intensity in Tryptyk z betonu, zmęczenia i śniegu (Tryptych in Concrete, Fatigue and Snow), particularly in the cycle Kątem u siebie (Wiersze mieszkalne) (Sheltered at Home [Apartment Poems]). In the poem discussed herein we get a foretaste of the metaphors to be used in those later works, a kind of template of the apartment block at a particular (but not favorite) time of day (morning, dawn) that will be continued in later texts.

In designating the space, the speaker attempts to situate himself in the building’s three dimensions, but also reveals the existence of a “fourth dimension,” expanding solid geometry to include the relationship that develops between the apartment block and the human being, marking the way a building conditions the behavior and attitude of an individual inside it.11)See Mildred Reed Hall, Edward T. Hall, The Fourth Dimension in Architecture: The Impact of Building on Behavior, Moline-Illinois-Santa Fe 1975, p. 15. This fourth, anthropological and potentially metaphysical dimension becomes the most important one in the poem. To what extent do the apartment block and its internal spatial dynamics organize the social existence of each of its residents? How do they influence the behaviour and feelings of the persona, how do they shape his experience?

A few years later, in his review of the book Odczepić się (Breaking Loose) by Miron Białoszewski, Barańczak notes: “New housing projects, box-blocks, sky-scrapers and cookie-cutter high-rises rising up out of the marshes driven through by trucks, for better or for worse, that is the permanent dominant of our landscape, the overpowering (though not particularly attractive) symbol of our contemporary life, the illustration of life as it goes on here and now.”12)S. Barańczak, “Widok z dziewiątego piętra. Pożegnanie z Białoszewskim” (View from the Ninth Floor. Goodbye to Białoszewski) in Barańczak: Przed i po: szkice o poezji krajowej przełomu lat siedemdziesiątych i osiemdziesiątych (Before and After: Sketches on Polish Poetry of the Late 1970s and Early 1980s). London 1988, p. 21. Where the Białoszewski poems discussed in that review can be read as a document of life in Communist Poland, poetical transformations in verse of the poet’s experiences living in an eleven-storey skyscraper on Lizbońska Street, Barańczak’s aim is clearly something other than recording the events, onerous attractions, and difficult but gradual, possible process of making a home for oneself. The author of Dziennik poranny (Morning Diary) has no wish to live in an apartment block, because it has become for him a symbol of captivity, indoctrination, and subordination to the authorities. Late twentieth-century modernist residential block architecture, disregarding the local and historical specificity of a place, lacking respect for the emotional and aesthetic needs of its inhabitants, brought with it a particular vision of the social order and expressed a belief in social planning architectural projects were supposed to be capable of transforming human nature. Architecture that relied on abstract, geometric shapes could become the perfect base for the formation of a collective susceptible to ideological control, stifling individual expression. In the same year that Dziennik poranny was published, a housing project was begun in St. Louis, Missouri, designed by Minoru Yamasaki as a model example of modernist style and recognized in 1951 by the American Institute of Architecture. It was the symbolic “death of modern architecture,”13)Wilkoszewska, Wariacje na postmodernizm, p. 165. while in Poland that architecture was experiencing a second youth.

One of the negative social effects of residential block construction was the formal and functional uniformity which it created, failing to satisfy social and cultural needs and not allowing the expression of individual aspirations. Importantly, the inhabitants of such architecture were not “able to feel an identification not only with their city, but also with their immediate vicinity.”14)See A. Basista, Betonowe dziedzictwo. Architektura w Polsce czasów komunizmu (Concrete Legacy. Architecture in Poland in the Communist Era), Warszawa – Kraków 2001, p. 121. The difficulty of making one’s home, the regularized and geometric organization of the surrounding space, the monotonous repetition of the structuresthat impose vertical and horizontal order on space are not so much thematized in the poem as shown via its structure, arising from the intersection of various systems, illustrating Zygmunt Bauman’s words:“All it takes to regiment the desires and activities of city dwellers is to make the system of streets and houses regular. All it takes to stop people from acting in disorderly, capricious and unpredictable ways is to rid the city of everything haphazard and unplanned.”15)Z. Bauman, “Wśród nas, nieznajomych – czyli oobcych w ponowoczesnym mieście” (Among Us Strangers, or On Outsiders in the Postmodern City) in: Pisanie miasta, czytanie miasta (City Writing, City Reading), ed. A. Zeidler-Janiszewska, Poznań 1997, p. 148. Unlike Białoszewski, Barańczak does not seek to explore the “poetic possibilities that paradoxically lie hidden in the sterile, boring landscape of a new housing project”;16)Barańczak, “Widok z dziewiątego piętra,”p. 21. he is not interested in the interaction between literature and architecture, as in the case of the poems written on Lizbońska Street, expressed through the adaptation of the poetic form to a new spatial situation,17)Instead of horizontal poems like “Leżenie” (Lying Down) in his book Było i było (Been and Been), Białoszewski writes poems in vertical columns about skyscrapers, tower-poems– verticalized, adapted in graphic shape to the form of a building, conveying spatial relations as well as the subject’s placement within them. On the poetry he wrote after moving to Lizbońska Street, see.: J. Grądziel-Wójcik, “‘Blok, ja w nim’. Doświadczenie architektury a rewolucja formy w późnej poezji Mirona Białoszewskiego” (Apartment Complex, Me Inside It. The Experience of Architceture and the Revolution in Form in the Later Poetry of Miron Białoszewski) in: W kręgu literatury i języka. Analizy i interpretacje (In the Sphere of Literature and Language. Analyses and Interpretations), ed. M. Michalska-Suchanek, Gliwice 2011. he is not attempting to fight the “boredom of apartment blocks.” The author of Wiersze mieszkalne (Apartment Poems) on the contrary is trying to expose the degrading and oppressive nature of such buildings. The poem discussed here is situated at the beginning of Barańczak’s trajectory down that path, unmasking the inhuman fourth dimension of the “residential machine,” using a long list to reveal the elementary and (intellectually and emotionally) shabby interior of the building.

When the persona begins to gradually take in the surrounding space, recognizing its regular features (“beneath” or “below me” and “above me” are mostly at the beginning of lines, while “on my left” and “on my right” are later in the line), he begins to look out on what lies beyond his apartment. The intersecting vertical and horizontal axes here function to impose order on space, and the four sides of the cross thus created are identified with the four directions, composing a basic figure of the division of space that spreads out to become increasingly abstract and vague: on the left we have a street that leads to the western suburbs, further on there are fields, highways, borders, rivers, and ocean tides; on the right“ a window, and beyond that, dawn,” or rather “gray splotches of dawn,” further on “other streets, fields, highways, rivers, / borders,” as it gets increasingly cold: “frozen steppes and icy forests.” The world outside is neither optimistic, nor varied, but rather anonymous, monotonous, and disheartening. Perhaps its division conceals a reference to the geographical and political layout of the world, evoking the countries beyond the western “wall” opening on the ocean on one side and the space of the steppes and the frozen tundra on the other. The space expanding along the vertical axis may elicit stronger emotions, stretched out, in keeping with the symbolism of the cross, between earthliness and immortality; there is a menacing undertone to “under me / a gulf of floors” (in Polish, the effect of the enjambment is intensified, coming after a much shorter line that disrupts the irregular syllabication), the basement and the “hermetically sealed” jars (the agglomeration of words broken up by enjambment underscores the evocation of closed spaces), and particularly what is located lowest of all: “foundations, earth, the fiery abyss.” Looking up, we find the attic, the strings, and the roof (and, somewhere in the ether, fear—in Polish, “strach,” featuring assonance and alliteration with regard to the previous words) and the ungraspable clouds, wind and increasingly pale and almost invisible moon and stars. The gulf and the abyss below seem considerably more tangible and convincing than this misty vision of the silent sky, and all of this cosmic imagery, catastrophic in origin, becomes trivialized by the perspective of the housing project.

The poem’s imagery invokes all of the elements: the ocean, waters, rivers, ice, frost, earth, the fiery abyss. It creates a panoramic, almost cosmic perspective, as if the persona suspended in his apartment block were able to see more and farther than is humanly possible. The world around him is unattractive and abstract, it is frightening, even blood-chilling. We find an internalized, private catastrophism here, devoid of visionary metaphors, a sense of community or the redemptive nature of annihilation its apartment incarnation resembles a kind of “little apocalypse,” an artificial “catastrophe-flavored” prophecy. The superficially stable, banal and rather boring everyday reality of the era of the “little stabilization” (the 1960s) with milk delivered to the doorstep every morning, stores of food ready for winter and laundry drying conceals disquieting signals that emerge in a lexicon of negative references, using the opposition “open-closed” (closedness, hermetic sealing, wall, border gulf, abyss, steppes, wind).

In the Christian symbolic tradition, the arms of the cross represented the four directions, and each detail of the environment was incorporated into the plan for salvation and endowed with sense: the Church Fathers taught that the right beam of the cross pointed east because light (and therefore salvation) come from that direction.18)M. Lurker, “Misterium krzyża” (Mystery of the Cross) in: Przesłanie symboli w mitach, kulturach i religiach (Meaning of the Symbol in Myths, Cultures, and Religions), trans. R. Wojnakowski, Kraków 1994, p. 395. The right side of Christ corresponds to vita aeterna (eternal life), suggesting his godliness, while the left side betokens vita praesens (temporal life), with the important condition that these sides are always designated from the point of view of the Crucified One. In Barańczak’s poem, the left side of “my body” shows a street leading to the western suburbs, and the light coming from the east is “in gray splotches” and portends a severe winter; the landscape around the cross is deprived of divine power and light, faded and bereft of hope, and only the abyss takes on the expressive color of fire. If the man lying on his back is meant to remind us of Christ on the cross, however, that symbolism is adapted to the realities of the apartment complex –trivialized, desecrated, and immobilized like the poem’s persona. There is a crucifixion, but without the prospect of salvation; there is “wznak” (lying on one’s back), but no “znak” (sign). We can state, in Barańczak’s phrase, that being in this apartment contains “something of life after death,”19)Barańczak, “Widok z dziewiątego piętra,” p. 22. a sleepy “half-life” without the promise of resurrection. The persona remains horizontal, shutting his eyes back up…

The text’s emotional dominant is the persona’s unconditional consent to remain motionless, his passivity, both physical and mental. “Relieved” at the intersection of vertical and horizontal, he says “yes” to his life; he not only cannot, but rather does not want to and makes no effort to change his situation, though he is also far from being a “praiser of recumbency,”20)Z. Łapiński, “‘Psychosomatyczne są te moje wiersze’. Impuls motoryczny w poezji J. Przybosia” (“Those Poems of Mine are Psychosomatic.” The Motor Impulse in the Poetry of J. Przyboś), Teksty Drugie (Alternate Texts) 2002, 6, p. 11. like the persona of a verse cycle Białoszewski wrote even before his move to the high-rise on Lizbońska Street. If we accept that the “fourth dimension” in space forces us to act a certain way, influences our emotions and causes our feelings to adapt to the place,21)See H. Buczyńska-Garewicz, Miejsca, strony, okolice. Przyczynek do fenomenologii przestrzeni (Places, Pages, Surroundings. A Contribution to the Phenomenology of Space), Kraków 2006, pp. 237-238. then in Barańczak’s persona this space elicits mainly passive states of mind (precisely the opposite of what happens in the apartment complex poems of Białoszewski22)In his Lizbońska Street poems, Białoszewski abandoned the recumbent lifestyle and took on an upright stance, ceaselessly standing by the window, running down the stairs, wandering the corridors, leaning out of the window physically and looking outside metaphorically also, living in the place by means of the meaning with which he endowed it.). “The human being experiences moods in relation to a place. A church has associations with moods of solemnity, calm, and ceremony, while a circus or busy street are the opposite, places of joy, amusement and merriment” analogously, the apartment complex in this poem, whose crossing vertical and horizontal lines bring to mind a prison,23)“The grid replaces the distinct and diverse places of the city, tightly packed with meaning and meaning-giving, with anonymous intersections and sides of identical squares; if the grid symbolizes something, it is the priority of the outline over the reality, of logical reason over the irrational element;the intent to subjugate the whims of

nature and history by forcing them into the framework of relentless, irrevocable laws,” Bauman wrote. “Wśród nas, nieznajomych,” p. 148. does not elicit any reaction in the persona, whether emotional or intellectual, besides disorientation and fear.24)According to Yi-Fu Tuana, “the body not only occupies space, but rules it through its intentions.” Yi-Fu Tuan, Przestrzeń i miejsce (Space and Place), trans. A. Morawińska, introduction by Krzysztof Wojciechowski, Warszawa 1987, p. 52. The subject makes no attempt to change anything in his reality, he does not spring into action, makes no effort to take initiative, to take control of or shape the space he describes; he simply occupies it, taking a submissive stance towards reality, even though that does not entail acceptance of his psychophysical condition. The subject is crucified, or rather paralyzed– by infirmity, passivity, or fear? Shut up “hermetically” in the apartment complex, dwelling somewhere in between the strings in the attic and the gulf of floors, he does not “stand out,” he does not stick his head outside as did Białoszewski,25)In the book Odczepić się (Breaking Loose) a persona locked out on the stairway of an apartment complex declares: “so what if / I stick out with gazes / fears / ecstasies” (“bo co iraz / wystaję /wyglądaniami / obawami / uniesieniami”). See M. Białoszewski, “Odczepić się” i inne wiersze opublikowane w latach 1976-1980 (“Breaking Loose” and Other Poems Published 1975-1980), Warszawa 1994, p. 73. also because the glaciated landscape and gray, uncertain dawn are rather forbidding. In the world represented there is no long-term perspective, because the persona, rigidly solidified in his apartment, has nothing to wake up for in the poem’s metaphysical space, there is crucifixion, but no resurrection.26)In contrast to how dawn functions in Białoszewski’s poems, in Barańczak’s poetic universe it cannot turn into day. Likewise in other poems in Dziennik poranny, at daybreak “darkness thickens,” “at dawn each day night must begin” (“ciemność gęstnieje”, “o świcie codziennie noc musi się zacząć” in “Och, wszystkie słowa pisane” [O, all written words]), and “At half past four in the morning […] the naked bodies of lovers” (“O wpół do piątej rano […] ciała kochanków nagie”) are sweaty “from dark consciousness” (“od jawy ciemnej,”in “O wpół do piątej rano” [At Half Past Four]). Also, in “1.1.80: Elegiitrzeciej, noworocznej z Tryptyku” (1.1.80: Third Elegy, at New Year’s, from a Tryptych) we read: “like a garbage chute / the abyss waits below us: / at the feet of a crowded apartment building / at the feet of the hungry globe” (“jak zsyp do śmieci / przepaść czeka pod nami: / u stóp ludnego bloku / u stóp głodnego globu”) and the request: (“send me long sleep / and let me open my eyes / when it’s all over” (“ześlij mi długie spanie / i niech oczy otworzę, / gdy już będzie po wszystkim”).

The cross represents “shameful humiliation and praiseworthy elevation, human suffering to the point of death and (as a result) the ascension into heaven of the Son of God”27)Lurker, Misterium krzyża, p. 389. – the problem is that in the apartment complex version of reality that second part of the picture does not come into being. The room seems to be a prison, and the bed a tomb, from which it is impossible to rise. On the other hand, crucifixion can here be understood as a death sentence, the customary punishment for criminals and slaves that the Romans used from the time of the Punic Wars.28)Ibid., p. 390. And in fact this non-religious meaning appears to dominate in the text; the building’s horizontal and vertical planes are filled up by earthly life, but nothing begins or opens in it, and the architecture reveals itself to be soulless and godless, containing totalitarian repression and captivity. Jerzy Kandziora claims that in Barańczak’s earlier work, the body becomes “a tool for the demystification of ideology”and represents “a pose of consenting to captivity,” and if it also registers “his ineffective, reduced existence within the four walls of the apartment,” that leads “to a generalization about the human condition,” sublimating the persona’s life. At the same time, Kandziora remarks that the persona of Dziennik poranny (Morning Diary) and Sztuczne oddychanie (Artificial Respiration) “experiences his stations of the cross in the everyday reality of the PRL. In the sphere of poetics, this corresponds to the narrative formula of looking in from the outside. Only the narrator, situated outside the world of the poem, a visionary, moralist commentator who performs a metaphysical diagnosis, can inscribe his persona in the tradition of the biblical and sacral, and compare his fate with that of the Crucified One.”

Throughout the poem “Where did I wake up” the speaker is engaged in an effort to locate his position in space: the first-person narrator places himself next to, over, and under, in the middle of the situation being described. In line 24 the persona’s declaration suddenly finishes with the word “yes” (“tak”), a pause after the caesura; from that point on, the perspective of the narration changes to the third person. The subject now looks at himself from the outside, taking the perspective that dominates later texts by the author on similar themes. The change in the persona’s point of view does not signify his mobilization, however, as would be typical for the modernist vision of urbanc space;29)See E. Rybicka, Modernizowanie miasta. Zarys problematyki urbanistycznej w nowoczesnej literaturze polskiej (Modernized Cities. Outline of the Urban Problematic in Modern Polish Literature), Kraków 2003, p. 109. movement here does not become a source of knowledgeand does not open a perspective on the external world. The subject’s re-embodiment does not render him dynamic, intellectually or otherwise: the persona is placed in a particular spatial, architectural, and existential situation, which he describes, but is he capable of interpreting it? The “relieved” man says only “yes” and “shuts his eyes” to reality, perhaps from fatigue, but more likely in a refusal to awaken, since awakening would mean accepting responsibility. On the other hand, the “I” who observes the man appears to understand more–he not only senses and registers the external world, but understands it; it is no accident that the head is placed at the intersection of all perpendiculars and planes. The overpowering force of the building’s and thus the system’s oppressive (crucifying) grid exerts its influence with particular strength on his way of thinking: the persona inhabiting the “concrete cave”30)From the poem “Mieszkać” (Living) in the cycle Kątem u siebie (Sheltered at Home). becomes homeless, when he stops thinking and surrenders to the architecture of the complex, when he “shuts his eyes,” when he does not resist. The detached “I” looking at his body from the outside completes the process of his objectification, while claiming for itself the right to evaluate and pronounce judgment.

The metaphysical interpretation offered by the body suspended in the anonymous space of the cosmos does not invalidate the other, horizontal body: the persona, crucified by the perpendiculars and planes of the complex, inscribed into its modernist geometry and worldview, becomes pinned to “every cross at once / by the steady nails of his pounding heart.” If one of the two is being privileged here, it is the one closer to the body– the anatomical one, the spine, our most private axis of the world, the support of the body that is unable or unwilling to stand upright or to rise from the dead. A crucified man cannot find the strength to change his position, since he does not have external support; the reason for the lack of meaning in the world appears to be the hazy and uncertain presence of Transcendence the moon has grown pale and the stars are barely visible. The human being must then endow things with meaning himself and that is why his position provokes another question, concerning his moral spine his social stance, the values he holds, and the strength of character that would allow him to get up and resist. The persona, lost in the space of the complex, recovers only his bodily form, and the description of his state of being remains remarkably psychosomatic: the rumbling, intensified, accelerated and loud rhythm of his heart may indicate fear, his terror of his situation “he” appears pinned to the cross by his own fear, overcome by impotence, and only his heart “emits a sound of cheap mortality,” to paraphrase a later poem in the cycle Kątem u siebie (Sheltered at Home).

Subsequent texts in Dziennik poranny say clearly and straightforwardly why the persona is afraid: in“Kołysanka”(Lullaby) “a faint trail of blood flows from my temple,” and when the time comes to get up, “you must force your neck into a collar of thorns”; in “Śpiący” (The Sleeper) “the day is heavier,” “the day is crafty, / without warning it goes […] for the jugular.” In a later poem from Sztuczne oddychanie, “N.N. budzisię” (N. N. awakens), the situation analyzed above repeats itself: the persona “Awakens. I am here. He is there. He opens his eyes,” and the internal voice reminds him of the question that he dreamed about, that has disturbed his sleep and thrown him off balance: “Who / am I?” “Just take it easy. Take it easy,” comes the answer, familiar to us, and the speaker, distancing himself from the main character, called N.N., diagnoses the situation: “he woke up on a new day, a new fear (am I here?), a new / uncertainty (who?)” Barańczak’s apartment complex poems from Dziennik poranny are far from optimistic: “I don’t know whether it’s possible now to read in those poems even a trace of faith that something will change if there is any such trace, I suppose it’s based on the idea of credo quia absurdum, stubbornness not supported by any empirical data,”31)S. Barańczak, Zaufać nieufności. Osiem rozmów o sensie poezji (Trusting Distrust. Eight Conversations on the Sense of Poetry), Kraków 1993, p. 114. the poet himself has said. The change that appears in Wiersze mieszkalne is based on the attempt to refuse to say “yes” and to express opposition through the gesture of the persona’s standing upright, taking an active position, open to the world: in the poem “Dykto, sklejko, tekturo, płyto paździerzowa” (Plywood, pulpwood, pasteboard, particle board), the persona wishes to stand up and be like a “simple prayer,” (“pacierz prosty”),despite the difficulty of attaining such a position. The persona of Dziennik poranny finds himself at the moment before the definitive awakening of his consciousness, but it is only a matter of time: “Sleep. A little while longer, / lift up your sleepy heads, your heavy heads / lift them up, all who labor by day” (“The Sleeper”).

translated by Timothy Williams

Przejdź do polskiej wersji artykułu

Przypisy

| 1. | ↑ | See A. Nasiłowska, Persona liryczna (The Lyrical Persona), Warszawa 2000, p. 49. |

| 2. | ↑ | On Barańczak’s system of expansion, see D. Pawelec, Poezja Stanisława Barańczaka. Reguły i konteksty (The Poetry of StanisławBarańczak. Rules and Contexts), Katowice 1992, pp. 60-62. I have engaged in a broader discussion of connections between Barańczak’s early poetry and TadeuszPeiper’s concept in Dziennik poranny, which is an offshoot and a critical continuation of the thought of the leaders of the early avant-garde, in “‘Zmiażdżona epopeja’. Dziennik poranny Stanisława Barańczaka a twórczość Tadeusza Peipera” (The “Crushed Epic.” Stanisław Barańczak’s Dziennik poranny and the Work of Tadeusz Peiper) in: J. Grądziel-Wójcik, Przestrzeń porównań. Szkice o polskiej poezji współczesnej (Space of Comparisons. Sketches on Contemporary Polish Poetry), Poznań 2010, pp. 114-130. |

| 3. | ↑ | See M. Rembowska-Płuciennik, “Propriocepcja” (Proprioception) in: Sensualność w kulturze polskiej (Sensuality in Polish Culture), http://sensualnosc.ibl.waw.pl/pl/articles/propriocepcja-394/ [accessed: 26.01.2015]. |

| 4. | ↑ | E. Rewers, Post-polis. Wstęp do filozofii ponowoczesnego miasta (Post-polis. Introduction to the Philosophy of the Postmodern City), Kraków 2005, pp. 67-68. |

| 5. | ↑ | J. Kandziora, Ocalony w gmachu wiersza. O poezji Stanisława Barańczaka (Saved in the Edifice of the Poem. On the Poetry of Stanisław Barańczak), Warszawa 2007, p. 105. |

| 6. | ↑ | Here, we are of course dealing with Barańczak’s signature poetics of the poem, heralded by the title of the poem “In One Breath,” with which he opened the eponymous collection, first published in December 1970, and reprinted two years later in Dziennik poranny (Morning Diary).The poem consist of one long, unfinished sentence, broken up into lines of irregular length, structured with a system of expansion, spoken in one breath and ordered only by punctuation, placing commas in the middle of lines; enjambment here works against syntax, rendering the words left in the clausula ambiguous through the tension generated between line intonation and sentence intonation. See Grądziel-Wójcik, Przestrzeń porównań (Space of Comparisons), pp. 121-123. |

| 7. | ↑ | On the importance of rhythm in Barańczak’s poetry in relation to his metaphysical worldview, see Joanna Dembińska-Pawelec, “‘Poezja jest sztuką rytmu’. O świadomości rytmu w poezji polskiej dwudziestego wieku (Miłosz – Rymkiewicz – Barańczak)” (“Poetry is the art of rhythm.”On the Consciousness of Rhythm in Polish Twentieth-Century Poetry [Miłosz – Rymkiewicz -Barańczak]), Katowice 2010. |

| 8. | ↑ | S. Barańczak, “Tunel i lustro. Czesław Miłosz: Świty” (Tunnel and mirror. Czesław Miłosz’s „Świty” in Barańczak: Pomyślane przepaście. Osiem interpretacji (Thought Abysses. Eight Interpretations), afterword by I. Opacki, ed. J. Tambor and R. Cudak, Katowice 1995, pp. 9-21. |

| 9. | ↑ | Krzysztof Kłosiński deals with this in his interpretation; see Kłosiński, “Ponad podziałami” (Beyond Divisions), in: ”Obchodzę urodziny z daleka…”. Szkice o Stanisławie Barańczaku (“I’m Celebrating My Birthday From Far Away…”. Sketches on Stanisław Barańczak), ed. J. Dembińska-Pawelec, D. Pawelec, Katowice 2007., pp. 24-25. |

| 10. | ↑ | Barańczak, “Wzlot w przepaść. Julian Przyboś: Notre-Dame” (Ascent into the Abyss. Julian Przyboś’s “Notre-Dame”) in Barańczak: Pomyślane przepaście, p. 31. |

| 11. | ↑ | See Mildred Reed Hall, Edward T. Hall, The Fourth Dimension in Architecture: The Impact of Building on Behavior, Moline-Illinois-Santa Fe 1975, p. 15. |

| 12. | ↑ | S. Barańczak, “Widok z dziewiątego piętra. Pożegnanie z Białoszewskim” (View from the Ninth Floor. Goodbye to Białoszewski) in Barańczak: Przed i po: szkice o poezji krajowej przełomu lat siedemdziesiątych i osiemdziesiątych (Before and After: Sketches on Polish Poetry of the Late 1970s and Early 1980s). London 1988, p. 21. |

| 13. | ↑ | Wilkoszewska, Wariacje na postmodernizm, p. 165. |

| 14. | ↑ | See A. Basista, Betonowe dziedzictwo. Architektura w Polsce czasów komunizmu (Concrete Legacy. Architecture in Poland in the Communist Era), Warszawa – Kraków 2001, p. 121. |

| 15. | ↑ | Z. Bauman, “Wśród nas, nieznajomych – czyli oobcych w ponowoczesnym mieście” (Among Us Strangers, or On Outsiders in the Postmodern City) in: Pisanie miasta, czytanie miasta (City Writing, City Reading), ed. A. Zeidler-Janiszewska, Poznań 1997, p. 148. |

| 16. | ↑ | Barańczak, “Widok z dziewiątego piętra,”p. 21. |

| 17. | ↑ | Instead of horizontal poems like “Leżenie” (Lying Down) in his book Było i było (Been and Been), Białoszewski writes poems in vertical columns about skyscrapers, tower-poems– verticalized, adapted in graphic shape to the form of a building, conveying spatial relations as well as the subject’s placement within them. On the poetry he wrote after moving to Lizbońska Street, see.: J. Grądziel-Wójcik, “‘Blok, ja w nim’. Doświadczenie architektury a rewolucja formy w późnej poezji Mirona Białoszewskiego” (Apartment Complex, Me Inside It. The Experience of Architceture and the Revolution in Form in the Later Poetry of Miron Białoszewski) in: W kręgu literatury i języka. Analizy i interpretacje (In the Sphere of Literature and Language. Analyses and Interpretations), ed. M. Michalska-Suchanek, Gliwice 2011. |

| 18. | ↑ | M. Lurker, “Misterium krzyża” (Mystery of the Cross) in: Przesłanie symboli w mitach, kulturach i religiach (Meaning of the Symbol in Myths, Cultures, and Religions), trans. R. Wojnakowski, Kraków 1994, p. 395. |

| 19. | ↑ | Barańczak, “Widok z dziewiątego piętra,” p. 22. |

| 20. | ↑ | Z. Łapiński, “‘Psychosomatyczne są te moje wiersze’. Impuls motoryczny w poezji J. Przybosia” (“Those Poems of Mine are Psychosomatic.” The Motor Impulse in the Poetry of J. Przyboś), Teksty Drugie (Alternate Texts) 2002, 6, p. 11. |

| 21. | ↑ | See H. Buczyńska-Garewicz, Miejsca, strony, okolice. Przyczynek do fenomenologii przestrzeni (Places, Pages, Surroundings. A Contribution to the Phenomenology of Space), Kraków 2006, pp. 237-238. |

| 22. | ↑ | In his Lizbońska Street poems, Białoszewski abandoned the recumbent lifestyle and took on an upright stance, ceaselessly standing by the window, running down the stairs, wandering the corridors, leaning out of the window physically and looking outside metaphorically also, living in the place by means of the meaning with which he endowed it. |

| 23. | ↑ | “The grid replaces the distinct and diverse places of the city, tightly packed with meaning and meaning-giving, with anonymous intersections and sides of identical squares; if the grid symbolizes something, it is the priority of the outline over the reality, of logical reason over the irrational element;the intent to subjugate the whims of nature and history by forcing them into the framework of relentless, irrevocable laws,” Bauman wrote. “Wśród nas, nieznajomych,” p. 148. |

| 24. | ↑ | According to Yi-Fu Tuana, “the body not only occupies space, but rules it through its intentions.” Yi-Fu Tuan, Przestrzeń i miejsce (Space and Place), trans. A. Morawińska, introduction by Krzysztof Wojciechowski, Warszawa 1987, p. 52. |

| 25. | ↑ | In the book Odczepić się (Breaking Loose) a persona locked out on the stairway of an apartment complex declares: “so what if / I stick out with gazes / fears / ecstasies” (“bo co iraz / wystaję /wyglądaniami / obawami / uniesieniami”). See M. Białoszewski, “Odczepić się” i inne wiersze opublikowane w latach 1976-1980 (“Breaking Loose” and Other Poems Published 1975-1980), Warszawa 1994, p. 73. |

| 26. | ↑ | In contrast to how dawn functions in Białoszewski’s poems, in Barańczak’s poetic universe it cannot turn into day. Likewise in other poems in Dziennik poranny, at daybreak “darkness thickens,” “at dawn each day night must begin” (“ciemność gęstnieje”, “o świcie codziennie noc musi się zacząć” in “Och, wszystkie słowa pisane” [O, all written words]), and “At half past four in the morning […] the naked bodies of lovers” (“O wpół do piątej rano […] ciała kochanków nagie”) are sweaty “from dark consciousness” (“od jawy ciemnej,”in “O wpół do piątej rano” [At Half Past Four]). Also, in “1.1.80: Elegiitrzeciej, noworocznej z Tryptyku” (1.1.80: Third Elegy, at New Year’s, from a Tryptych) we read: “like a garbage chute / the abyss waits below us: / at the feet of a crowded apartment building / at the feet of the hungry globe” (“jak zsyp do śmieci / przepaść czeka pod nami: / u stóp ludnego bloku / u stóp głodnego globu”) and the request: (“send me long sleep / and let me open my eyes / when it’s all over” (“ześlij mi długie spanie / i niech oczy otworzę, / gdy już będzie po wszystkim”). |

| 27. | ↑ | Lurker, Misterium krzyża, p. 389. |

| 28. | ↑ | Ibid., p. 390. |

| 29. | ↑ | See E. Rybicka, Modernizowanie miasta. Zarys problematyki urbanistycznej w nowoczesnej literaturze polskiej (Modernized Cities. Outline of the Urban Problematic in Modern Polish Literature), Kraków 2003, p. 109. |

| 30. | ↑ | From the poem “Mieszkać” (Living) in the cycle Kątem u siebie (Sheltered at Home). |

| 31. | ↑ | S. Barańczak, Zaufać nieufności. Osiem rozmów o sensie poezji (Trusting Distrust. Eight Conversations on the Sense of Poetry), Kraków 1993, p. 114. |